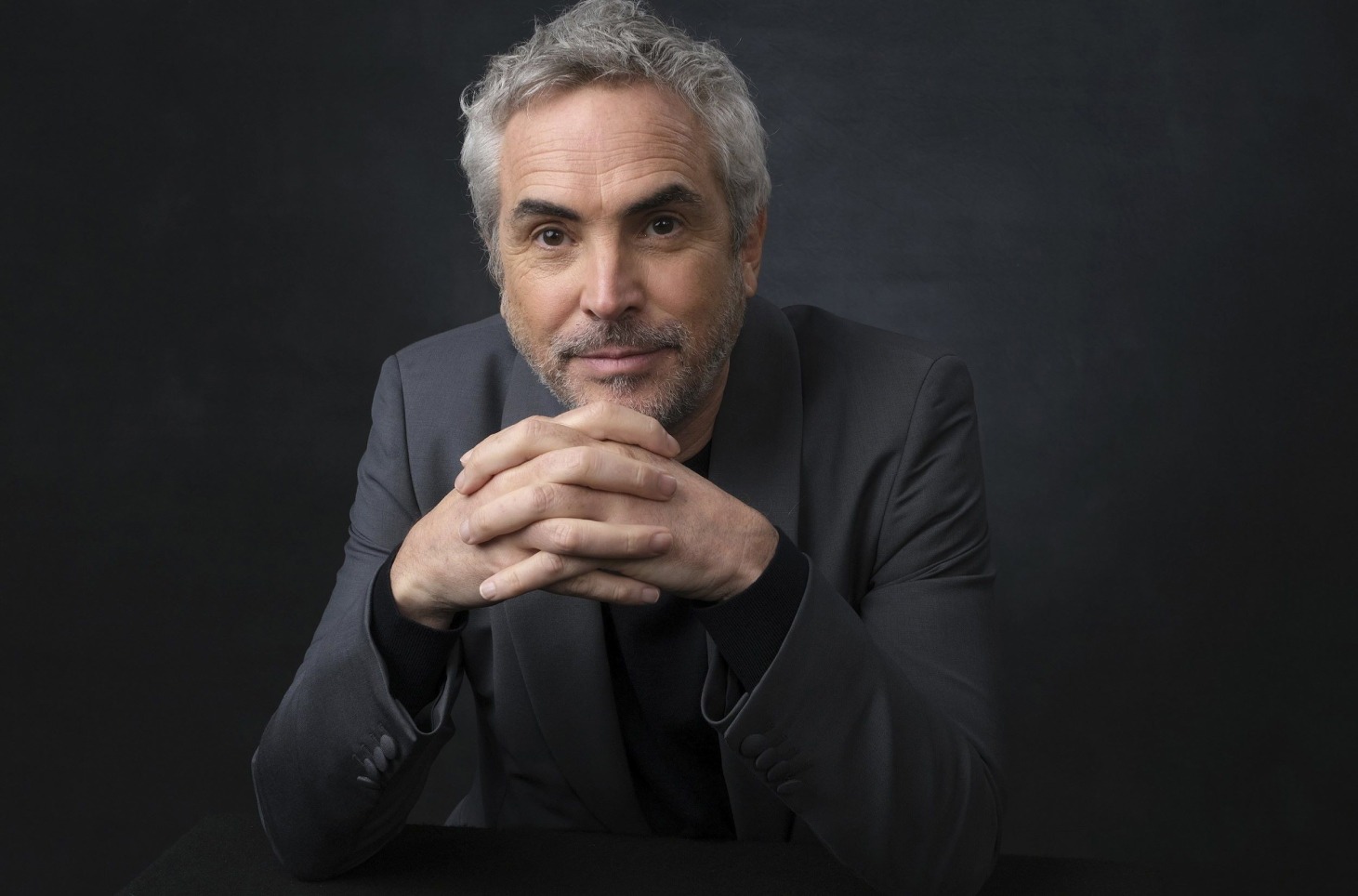

Alfonso Cuarón on his 30 favourite films ever, advice for filmmakers, watching movies, and the inspiration to become a film director.

A brief overview of Alfonso Cuarón before delving into his own words:

| Who (Identity) | Alfonso Cuarón is a Mexican filmmaker known for his diverse and impactful body of work. He has gained widespread recognition as one of the leading directors of his time, celebrated for his storytelling and visual style. |

| What (Contributions) | Cuarón has directed and written several acclaimed films, including Y Tu Mamá También, Children of Men, and Gravity. His 2018 film Roma earned multiple Oscars, including Best Director. Besides directing, he has also produced films and contributed significantly to the film industry with his unique approach to filmmaking. |

| When (Period of Influence) | Cuarón’s influence started in the early 1990s and grew significantly with his 2001 film Y Tu Mamá También. He continued to gain recognition in the 2000s with Children of Men and solidified his place in film history with Gravity in 2013 and Roma in 2018. |

| Where (Geographic Focus) | Born in Mexico City, Cuarón’s work is deeply connected to his Mexican roots, though he has also made a substantial impact in Hollywood. His films often blend the cultural richness of Mexico with the broader appeal of international cinema. |

| Why (Artistic Philosophy) | Cuarón is driven by a desire to tell stories that explore the human condition. He focuses on realism and the emotional depth of his characters, often highlighting social and political issues through their personal experiences. |

| How (Technique and Style) | Cuarón is known for his use of long, uninterrupted shots and his attention to detail. He often collaborates with top cinematographers to create visually stunning films. His style combines technical innovation with a focus on character-driven stories, making his films both visually impressive and emotionally resonant. |

This post features a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with references found at the end of the article.

Quotes & Excerpts

Advice For Filmmakers

I know there’s stuff that I regret, and I regret it just because I didn’t have the tools and experience when I was younger. But one thing is not to seek refuge in technique. There’s a comfort that can be taken in technique, and it can be very dangerous. Try to recognize film as a language as early and as soon as possible—not film as something that inherits from literature or drama or painting, but something that is an art in itself. It’s a language in its own form, and try to write and direct for that form.

Another thing is not to allow yourself to be sidetracked. For many years in my early career, I forgot that I was a writer because screenplays were available, and I think I lost several years of my creative life because of that. 1

Stick with the reason why you want to make films and be uncompromising about it. Don’t think of it in terms of work of industry because that would only be a bi-product of your talent and work. 2

His 30 Favourite Films Ever

P.S. We’ve created a Letterboxd list of the following 30 films for easy reference, so you can ‘like’ the list to save it to your account or add individual films to your watchlist.

Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica – 1948)

A Trip to the Moon (Georges Méliès – 1902)

Woman in the Moon (Fritz Lang – 1929)

Her (Spike Jonze – 2013)

Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000 (Alain Tanner – 1976)

Annie Hall (Woody Allen – 1977)

Marooned (John Sturges – 1969)

Some Like It Hot (Billy Wilder – 1959)

The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola – 1974)

Mean Streets (Martin Scorsese – 1973)

The Horse Soldiers (John Ford – 1959)

That Uncertain Feeling (Ernst Lubitsch – 1941)

The Great Beauty (Paolo Sorrentino – 2013)

Stagecoach (John Ford – 1939)

2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick – 1968)

The Right Stuff (Philip Kaufman – 1983)

Tokyo Story (Yasujirō Ozu – 1953)

Trouble in Paradise (Ernst Lubitsch – 1932)

Light Years Away (Alain Tanner – 1981)

Apollo 13 (Ron Howard – 1995)

The Long Voyage Home (John Ford – 1940)

The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola – 1972)

Jaws (Steven Spielberg – 1975)

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese – 1976)

A Man Escaped (Robert Bresson – 1956)

Faust (F.W. Murnau – 1926)

Avanti! (Billy Wilder – 1972)

I Don’t Want to Be a Man (Ernst Lubitsch – 1918)

Mouchette (Robert Bresson – 1967)

Lolita (Stanley Kubrick – 1962) 3

Writing Process And Routine

It takes a while before actually I sit and write. It is a longer process of a lot of research. It’s a research that is combined by researching books in which the place is a sofa, pretty much horizontal position or feet on some kind of surface or a hammock. That can take months and months, and that’s combined with phone calls to, in many cases, experts or visits to them, talking to them, and so on before I even start writing.

In Roma, it was a different experience because the research was my own memory. That required a lot of horizontal position in sofas or hammocks, where it was more about getting lost in my memories. But when the actual writing process begins, after that, there’s a lot of process that is again on the sofa or a hammock that can be extended, and walks, and just doing domestic activities while thinking out, thinking out, thinking out.

I have to say, once I write a screenplay, I think that all the screenplays I’ve written have been written maybe in three weeks. The thing that takes longer is the thought-out process. Once I’m writing, the process is generally one more time. So, I would put my feet on a coffee table or something, and computer on the legs, just writing like that. Once in a while I try to pretend I’m disciplined I sit down with the computer at a table.

Any screenwriter is writing for the screen, you know, writing for all of that stuff that is there to be conveyed in pictures ultimately. So, one way or another, all writers have to visualize. I believe the more visual the screenplay is, it just makes an easier journey for the director. So yes, and of course, I’m visualizing. When I’m writing stuff, I’m seeing that stuff.

I have collaborated with other writers or directors in writing, and when doing that, I’m describing stuff, and the director may do it differently, but there’s already a rhythm in terms of the flow of the film. So, I think it’s very important to think in terms of pictures.

Every single thing I’m going to write, there’s almost a fear of diving into the water. But once you start the scene, everything flows. It’s like if you jump into the water and start swimming—you enjoy the water. But the toughest thing is that first line, and how you’re going to start because once you have that first line, everything starts to make sense. But that’s always the hardest thing. 1

I spend a lot of time thinking about the elements that will make up the film, and most of these elements are in the screenplay. That’s what I love about screenwriting. I don’t consider myself a writer in the traditional sense—I’m not sure I could write a book. What I aim to do is create those elements on the page that can be transformed into a cinematic experience. I love the combination of sounds, characters, dialogue, and the context surrounding everything.

But I also try to convey a sense of time on the page. I’m not a fan of the minimalist approach to writing, where descriptions and dialogue are kept to a bare minimum. I feel that can sometimes distort the flow of time. I prefer that if something is going to last four minutes on screen, it’s represented fully on the page.

That’s why I don’t enjoy screenplays that simply describe a big battle with filler words to give a sense of the battle. A battle, like anything else, has a structure in time. Even if the director doesn’t follow every beat exactly, it’s important to have that sense of rhythm and flow on the page. 4

The Inspiration To Become A Film Director

To quote the opening of Goodfellas, “For as long as I can remember I always wanted to be” a film director. When I was a kid, my friends found me to be very annoying because while they wanted to play soldiers, I was pretending to film a movie about soldiers. I was staging them and trying to direct their actions. Later, as soon as I was able to hang on the streets by myself, I would go to the cinema at least once per day.

I always enjoyed the experience of going to the cinema and loved the moment of expectation before the curtain rose. I have always been enamored not only by the stories but also by the language of cinema; how stories and performances but also visuals and sounds could project emotions. I would see movies over and over, deconstructing the scenes. I was obsessed with trying to figure out the mystery behind it. 5

I wanted to be an astronaut. But soon, I knew I wanted to make movies, though I didn’t know what that meant. Then I saw two documentaries: one of Sergio Leone making a Spaghetti Western, and the other about George Roy Hill making “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” And I got it! There was this person making all these decisions, and all the trickery behind the scenes, the balsa wood and the explosions that wouldn’t hurt anybody. I thought, “That’s what I want to do.” My mom was very supportive. She found it cute, I guess. But she said I had to have a career, so I studied philosophy at (the) university. As if that would solve my career problems!

But (mom) was happy. I entered film school at 16 or 17. Chivo (Emmanuel Lubezki), the cinematographer, started two years later, and we started collaborating. At that time the big directors were Bergman, Fellini and Kurosawa. Then I was in love with Coppola, Spielberg and Scorsese, and films from the 1950s, plus Billy Wilder, Lubitsch and John Ford. That’s been a curse in my filmmaking. Some of my peers and friends have a consistent trait in their films, but mine go from one to the other. Maybe I’m a movie director and not an auteur. 6

I have this first glimpse of a memory of a film that I saw, but for many years I only remembered one second of it. It was Merlin getting his beard stuck in the door in The Sword in the Stone.

But as a child, I didn’t differentiate between films, make-believe, what an actor or a director was, or what a screenplay was. Everything was kind of the same thing for me. Cinema was all one thing—it was some sort of make-believe. The films I watched, everything was make-believe, and I was addicted. I wanted to see more, whether in the cinema or on television.

As a child, I also got into certain TV shows of that period. But again, there wasn’t much of a difference between one thing and another. Then I started going to the cinema more often, or as often as I could, or watching films on television.

One night, my parents went out for dinner, and my cousin was staying with me. We decided to break into my parents’ room and watch television, hoping to watch adult shows. A film was about to play—films used to air late at night—and it had a warning that it was only for adults. For some reason, I didn’t understand, but I watched that film, and it completely changed my perception of cinema. That film was Bicycle Thieves, and I found myself crying, completely moved.

I was exposed to something very different from what I had known before. At that point, I already knew what a director’s job was because I had seen a documentary about the making of one of the Sergio Leone films and also the making of El Cid. So I knew that the director was that person, and that’s what I wanted to do.

However, with Bicycle Thieves, I was very confused. I didn’t understand what the director had done. It was a story that was very emotional but, at the same time, very grounded in reality without any ornaments. That film pretty much sparked my curiosity to see more of those kinds of films. So, I would try to sneak in at night to watch those films. 7

Finding Joy In The Screenwriting Process

Joy is the thing that has to lead the process. If I have to define the moments of joy in the process of filmmaking for me, it is writing. Because in the moment that you are alone, there are no limitations, there’s no constraint of time, there’s no constraint of money—unless you have to pay the rent and then you have to deliver the draft. But that is the moment.

I love when you get lost, and if you have to travel, instead of falling asleep on the plane or watching a movie—it’s fantastic to watch movies, bad movies on planes, not good movies, bad, bad, bad movies—and you cry. So it’s great, but you don’t even do that because you just want to keep on writing. It’s just such an amazing thing, and you just get lost in that zone. Because from then on, everything goes downhill. The rest of the process is painful. 8

The Essence Of Cinema

For me, cinema is this language in its own right, in which all of these other things around are just tools for the sake of that language. What I’m saying is that you have seen amazing films, masterpieces that have been done without sound, without music, without color, without actors, even without stories. But there is not one single masterpiece that has been done without images. The image as an image flowing in time—this is the thing. What matters are those images flowing in time.

But I have to say, most of contemporary mainstream cinema is the kind of cinema where you enter the theater, get your popcorn, sit down, the lights go off, you close your eyes, you eat your popcorn, the movie ends, and you didn’t miss one bit. It’s more like books for lazy people. When it’s about being cinematic, it’s when the dance between the elements is greater than the sum of the elements. That is what is amazing. That is what I consider cinematic. 8

I believe that cinema is a language in its own form, in its own right, it’s a language, that requires a lot of different tools. The different tools, you know you have sound, you have performance, and of course, for certain kind of films, the films that I do, the narrative films, the screenplay is kind of the fundamental tool.

But those screenplays should be serving, it’s very different to write, serving a literary material, meaning something that is going to be, that the purpose of that is to be read in a book. As opposed to something in which the goal and the end of it is to be seen on the screen.

So I think as screenwriters we need to recognise that film language, how that this particular art in which narrative is constraining time, and that’s something that I find very beautiful because, when you’re reading a book, a piece of, a novel, you get immersed, you get lost in those pages, but you’re not bound by time. And what I find is that, the sense of time binds us with the now.

When we are experiencing a film we are in one hand lost in that universe, in that experience, but by the same token we are breathing that experience for as long as it lasts. You know a book can last, you can read a book in two days or in four weeks; a film you end up watching just the length of it. And I think that that’s something that is so important in the process of screenwriting, is that sense of the experience that we’re going to have in real time. 4

Film is not just this thing of illustrative pictures, it is something way more complex than that. It also doesn’t owe anything to literature or to drama or to painting. Cinema is way more similar to music. It’s an art that flows in time, that is also an abstract language, and that flows with themes. 4

Embracing The World Of Harry Potter

I hadn’t read the books. I hadn’t seen the movies. All I knew is that it was a family film and the third part of a franchise. That sounded really bad to me. I was just not interested.

But then I read the book. I fell in love with it. I saw the potential. In a way, I was coming out of “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” which is the journey of two teenagers seeking their identity as adults. Here with Harry Potter, it’s the journey of a kid seeking his identity as a teenager. So I felt that I was in a very comfortable place.

When I read the book, I was — I don’t know why, but I was connecting with it. The structure of this book is very cinematic. So for me, I was not that concerned after that. I was concerned about the other elements that were already in place.

I really loved what Chris Columbus, the director of the first two films, left me. First and foremost, he chose Stuart Craig, the production designer, who’s someone I’ve always admired. I think he put together an amazing group of actors. So I felt very comfortable working with those actors, with those sets, knowing that I would be able to build more sets and cast new actors. 9

When I was deciding whether to direct Harry Potter or not, a good friend of mine, Guillermo del Toro, told me, “You have to do this. But don’t try to do your thing. Just try to serve the material. And if you serve the material, you may create your most personal film.”

It was an interesting process, actually. It was the opposite of any other creative process I’ve been through. It wasn’t about what I wanted to do; it was about what the material needed, what it was calling for. It wasn’t about making it different from the first two films; it was about serving the material. And when you offer yourself in that way, it’s interesting how many other creative doors open up — doors that you didn’t know existed. It was a very interesting experience.

For instance, I had to throw away my ego of what I would do or not do. I was just going to serve the material. Ultimately, everything was going to be influenced by that. 9

Guiding Actors Through Emotional Depth

I asked the three kids [the stars of Harry Potter] to write an essay in the first person from the standpoint of their characters, doing a bio of their characters from the moment they were born to the moment the movie starts, but investing emotionally — not with the character’s emotions, but with their personal emotions for these characters.

For me, it was important to ground the performances in a real place, not in a wizardry place, but in human emotions because my theory was that if you ground everything in reality, then the magic is going to spring out just because it is there. 9

Meeting Guillermo del Toro For The First Time

Guillermo is another blue-collar of cinema, and we share a lot of insecurities and ball and chains, you know, and I think it’s something that has bonded us from early in our lives. I was early on a boom operator—I did 12 films as a boom operator, for instance, a microphone holder, you know. And Guillermo was an assistant makeup artist. I heard everybody talk about this genius of Guadalajara, you know.

Even if I was just a blue-collar worker among the young generation of filmmakers, I was known as someone with possibilities, you know. So when I started hearing about this weird guy from Guadalajara that was full of possibilities, I got a little jealous. And I didn’t meet him for a long time. All my friends worked with him, and they all just thought wonders and how weird he was. It wasn’t until I was doing a TV show in Mexico before I did my first film, which was some sort of Twilight Zone—Guillermo and I called it the “Toilet Zone” because of the budgets and so on—that Guillermo and I met.

I did my first one, and you got to write and direct and do everything. You had all the freedom to do your little thing, you know, and I did it. You shot for three days, and I was so proud of the result. It was loosely based on a Stephen King short story. Then, when I was in the production office waiting for the producer in the waiting room, there was this guy—this weird guy—just looking at me, looking at me. He had done one too. I heard that Guillermo had done one of those, and it was this one awkward thing of two guys knowing who the other guy was but being cautious.

He literally says, “You’re Cuarón?” I said, “Yeah.” “You’re Guillermo?” “Yeah.” He says, “You did that thing that’s based on Stephen King?” I was surprised that he knew the reference. We started discussing Stephen King and how great that short story was. Then he takes a pause and says, “The short story is great, so why does your short suck so much?” And I was like, “What?” He started explaining to me why, and he was absolutely right. Then we became best friends ever since. 10

His First Directing Job In America

The first job I had in the U.S. was an episode of Fallen Angels, produced by Sidney Pollack. I was terrified. They gave me this—it was five short films. All of them were based on short stories of film noir crime classics from the 50s and 40s. Not only that, but they had top directors directing everything: Steve Soderbergh, who was famous after Sex, Lies, and Videotape; Jonathan Kaplan, who had won the Oscar for The Accused; Phil Joanou, who was the most famous young guy at the time; and also Tom Cruise directing one, and Tom Hanks directing another. And I was the new guy.

My English was so-so, and I was scared of everyone. On top of that, every time I had my six days to shoot, they would come back and say, “You know what? Now you have five because one of the Toms needs one more day.” And then I had my location that I loved. I prepared my location, and they said, “Hey, you know what? The other Tom likes your location. He’s going to take it.” So I had no location.

I was like the ugly duckling, and I was terrified. I was working with Laura Dern, Diane Lane, and Alan Rickman, and I was terrified of them. On top of that, the location—a beautiful Frank Lloyd Wright house—was under the Hollywood sign. I would arrive and say, “Oh!” And the thing is, Alan Rickman can be very intimidating. He could be very intimidating just because he’s very serious, with this super deep voice, and he’s very short in his expressions but very clever and sharp. I was terrified of all of them.

So the first day, I started shooting, and it was a mess. I completely lost it at the end of the shoot. I was really suffering. By the end of the shoot, I had only done a quarter of what I was supposed to do. So, I stayed at a terrible motel near the set, in the closest motel I could find—a very seedy motel in Hollywood. I wanted to cry—literally, I wanted to call my mom. And the next day, I arrived terrified. The AD, the assistant director, came and said, “Hey, Alan and Laura want to talk to you.” I was dreading the moment. I genuinely thought, “Okay, this is the moment that I’m fired.”

I walked to this room where they were, this office, and there they are. Alan says, “Hello, Alfonso,” and it was like… you know that character in Harry Potter? He was like that. So, I sit, and Laura starts very sweetly and says, “We’re here for you. The reason we’re here is we saw your film, and we know that you’re a great director.” Then Alan says, “We’re here for you. You have to tell us exactly what you want. We’re going to do it. We’re supporting you. You’re a great director.” They kept on telling me that—they saw, and they knew I was a good director. They said, “Please, just tell us without fear what you want.”

So, I came out of that, and what happened was nothing short of a miracle. We started shooting, and I said, “Okay, where do we start?” They said, “We’re going to repeat the whole day yesterday.” I responded, “You can’t. You’re already far behind.” They insisted, “I don’t care. We’re going to repeat the whole day.”

I’m sharing this because it’s an example of how people who cross your path in life and give you a vote of confidence can change everything. That day, I shot everything from the day before, everything from the second day, and half of the third day, all in one day, just because I had the embrace of those people.

I would be crazy if I talked about my career as something that’s only about myself. It’s about Sidney Pollack, about these people, about Luis Estrada in Mexico, José Luis García Agraz in Mexico—so many people who paved the way for me. In the end, I finished on time, and that was the show that won awards among all the others in the series. 7

Watching And Learning From Movies

I try to watch as much as possible. For me it’s not about making movies, it’s about getting older and taking on more responsibilities — family and stuff — so when I was in my youth I’d go to the movies every single day. Sometimes twice a day. Eventually, you don’t have the time for that. But I definitely still watch whenever I can. It’s almost like a need for me to be connecting with cinema. And I have eclectic taste, I like a good fun movie too, but it has to have something.

I don’t like generic films, they bore me to tears. The original Poseidon Adventure is one of my favorite films. I love that film. But then I also love Tarkovsky. When I saw The Poseidon Adventures as a kid I was surprised. I’ve seen it many times in my life now and every time it feels like an original film. There’s something specific about it that I truly enjoy.

Obviously, there’s a certain level of sophistication and engagement I can get with that kind of cinema. When I say I enjoy cinema it’s from something fun like that. But I am really engaged and deeply moved when I’m confronted with a challenging piece of cinema, and I try to keep on connecting. I try to keep more or less relevant to what’s happening every year.

I like to learn from the new masters, though I do like to revisit old films. There’s only so much you can learn from the old masters. There’s a point where you have to connect to the younger masters because they’re bringing the refreshing cinema. If you don’t learn from the young masters you’ll become stale. 11

The actual success of a film is only dictated by time. It is the only true judge of what films are successful and which ones are not. Young films are successful for one year and forgotten two years later. For me, the only reason that I’ll make a film is for what I’ll learn for the next one. The learning curve, for me, is what marks the success of my films. 11

Overcoming Doubt To Write His First Film

It took me a long time to direct my first film. I mean, there were many different factors—one was an insecurity about writing, I guess. It was interesting; yesterday, I had a conversation at a school, and you could see that anxiety about the writing, and I completely relate to them because it’s very daunting. I really thought that I couldn’t do it, and I was always trying to write a screenplay, and it didn’t work.

But the other important factor was that, very early on, I started having a career in different positions in film for survival, more than anything else, for money. Also, I had a son when I was very young—I was 20 when I had a son. So, film pretty much became my way of earning a living. I worked as a boom operator on like 12 films; I worked as an assistant editor; I worked as an assistant cameraman. I would do little gigs as an editor myself or as a cameraman in very, very small projects.

But my longest career then was as an assistant director, and I really thought that I was not going to have a career anymore. I would see all my peers, people I collaborated with in film school, directing films while I was an assistant. It was kind of a sad resignation.

I was very lucky that I was offered to do these episodes of a TV thing that was more like Twilight Zone, you know, little shorts. I could write my own short and direct it. So I wrote, directed, and photographed some of my own stuff, and I edited some of it.

It was then that Chivo [Mexican cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki] asked me, very candidly—without any intent to be offensive—he just asked, “So what’s your next step? After doing these things, are you going to do telenovelas?” I was so offended, but at the same time, he put me in my place because I was like, “What the heck am I doing?” That’s when my brother Carlos and I wrote my first film. 7

Key Takeaways

This section provides practical insights based on the quotes featured in the article, serving as a reference to inspire and guide you through your own creative journey while navigating challenges.

- Film as a Unique Language: Film is an art form of its own and not merely an extension of literature, drama, or painting. Focus on mastering film as a language that conveys meaning through images flowing in time.

- Stay True to Your Vision: Avoid being sidetracked by the industry. Always stick to the reason why you want to create films, and don’t compromise your vision for the sake of fitting into the industry.

- Writing Takes Time: Alfonso Cuarón’s writing process emphasizes deep thinking and reflection. Don’t rush the process; allow yourself to think deeply and visualize every detail before beginning to write.

- Fear of Starting: Overcoming the fear of starting a project is essential. Often, the hardest part is writing the first line, but once that is done, the process begins to flow.

- Embrace Cinematic Thinking: As a screenwriter, think visually. Writing should serve the purpose of creating a cinematic experience, and screenplays should be approached with the rhythm and flow of film in mind.

- Joy in Creation: Find joy in the writing process, especially the freedom of early drafts when there are no limitations or constraints. This joy is essential to sustaining the creative process.

- Learning from Films: Watch a wide variety of films, both new and old. Learning from the younger masters keeps your work fresh, and revisiting classics teaches you invaluable lessons.

- Trust in Collaboration: Working with actors or collaborators is about guiding them through human emotions rather than dictating every movement. Trust them and ground performances in reality.

- Use Failure as Growth: View failure as a tool to grow and learn. Cuarón acknowledges that some early mistakes happened because he didn’t have the right tools, but these failures shaped him.

Creative Challenge

This creative challenge encourages you to take action and apply insights from Cuarón’s quotes, helping you explore your creativity and overcome obstacles in the process.

Objective: Embrace Cinematic Visualization

Enhance your ability to think and write visually, focusing on how to communicate emotion, story, and flow through images.

Process:

- Scene Selection: Choose a scene from your current writing project or a short film idea you have in mind.

- Visual Breakdown: Before writing the scene, sit down and close your eyes. Visualize every element of the scene—how it will look, the colors, the movements, and the camera angles. Spend at least 10 minutes fully immersing yourself in this visualization.

- Write Cinematically: Now write the scene, focusing on the visual aspects. Don’t just describe what happens but focus on how it looks. Use minimal dialogue and rely on visuals to tell the story.

- Refine: After writing, read it over and see where you can cut out unnecessary words or dialogue, allowing the visuals to do the storytelling.

Outcome: Reflect on how focusing on the visual elements improved your scene. By emphasizing imagery over words, you will develop a stronger sense of cinematic storytelling.

Useful Resources

We’ve created two Letterboxd lists for easy reference, so you can ‘like’ each list to save it to your account or add individual films to your watchlist:

Next up: James Murphy on on How He Overcame Fear Of Failure

References

- Alfonso Cuarón on Writing the First Line of a Movie | On Filmmaking, Bafta Guru

- I am director Alfonso Cuaron of Gravity and other films. Preguntame casi todo. AMA!, Reddit AMA

- Alfonso Cuarón names his 30 favourite films of all time, Far Out Magazine

- BAFTA Screenwriters Lecture Series: Alfonso Cuarón, Bafta.org

- What inspires individuals to become film directors and why?, Alfonso Cuarón, Quora

- Alfonso Cuaron Q&A: ‘Gravity’ Director Reveals Early Influences, Variety

- In Conversation with Alfonso Cuarón – Filmmaking is an Instinctive Process, Locarno Film Festival

- Alfonso Cuarón on What “Cinematic” Means, Antoine Petrov

- Alfonso Cuarón, Charlie Rose Interview

- Festival de Cannes 2017- Masterclass with Alfonso Cuarón, YouTube

- Alfonso Cuarón Reveals His Ghost-Perspective, His Influences, and a Theory He Hates, nofilmschool.com