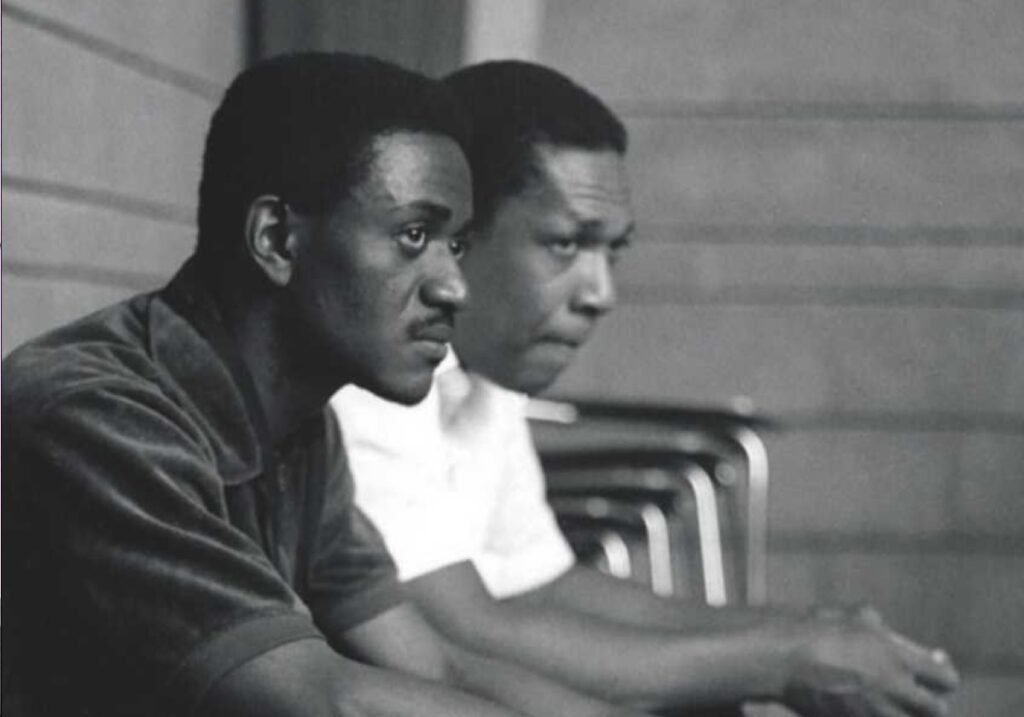

Pharoah Sanders on working with John Coltrane, honesty and self-expression, how to play music creatively, and spirituality.

Pharoah Sanders (1940–2022) was an Arkansas-born tenor saxophonist who fused free-jazz fury with deep spiritual lyricism. From Coltrane sideman to Karma auteur, his overblown multiphonics and Eastern rhythms re-wired modern jazz—and still echo on Floating Points’ 2021 collaboration Promises.

Quotes & Excerpts

This post features a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with references found at the end of the article.

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

I started playing drums first. Then I wanted to play clarinet. I went to church every Sunday, and there was this memo up in church that someone had a metal clarinet. That person just passed away maybe a few days ago. He was about ninety-three or ninety-four. That’s how I got my first instrument. Seventeen dollars!

In high school I was always trying to figure out what I wanted to do as a career. What I really wanted to do was play the saxophone—that was one of the instruments that I really loved. I started playing the alto. It’s similar to the clarinet—if you can play the clarinet, you can play the saxophone.

Tenor was the most popular instrument at that time to get work. I would rent the school saxophone. You could rent it every day if you wanted to. It wasn’t a great horn. It was sort of beat-up and out of condition. I never owned a saxophone until I finished high school and went to Oakland, California. I had a clarinet, and so I traded that for a new silver tenor saxophone, and that got me started playing the tenor.

The minute I bought it, I wanted an older horn, so I traded my new horn for an older model. I had to get it all together. I didn’t know enough about lots of things—basic things. I knew I needed to get some studying in, in order to get into playing saxophone, because I wanted to play jazz. So I had to cut out a lot of activities that I was doing and spend more time practicing scales and stuff like that. 1

When I finished high school, I went to college in Oakland, California, when I was about 18. At that time, I wasn’t planning to go to music school. I wanted to become a painter. I haven’t painted in years now and would like to get back to that. I can draw and paint, but then I started hearing other people play. Like Rollins, Charlie Byrd, Clifford Brown, and John Coltrane of course, and that has been taking me on and on into music. 2

The reason I switched from clarinet to alto saxophone to tenor saxophone is I wanted to be a player at the time; I wanted to learn how to play the blues and all that. I kept hearing the blues on the saxophone. I didn’t hear no clarinet in my hometown. And the only jobs around in the clubs were blues jobs. My father had a collection of records, and I would listen to tunes like ‘After Hours,’ ‘Blue Flame,’ ‘Caldonia’ with Louis Jordan. I learned a lot from playing the blues down in the South, and there were a lot of great blues singers in Arkansas, like Albert King and many others. 3

Surviving as a Musician

I’ve been getting publishing royalties and stuff like that. I have just been lucky. They come in at the right time. Sometimes they don’t, but I am not wealthy or anything like that. I just love to work. I would rather work three hundred and something days out of the year. I would rather be working. They don’t realise I love playing, because then I can really get my music together. If I don’t do that, then my chops go down and stuff goes down. 4

I would tell them to learn as much as you can, get your education. New York City, it’s a place where you’ve got to have money. You don’t need a car, there’s a subway, but you need money to eat, and that was my concern every day. 5

Working With John Coltrane

His whole demeanor reminded me of a minister. He didn’t act like a lot of musicians that I’ve met in my life. John, he was always extremely quiet. He didn’t say anything unless you asked him something. I never asked him anything about music.

He always had some kind of a way of looking to the future, like a kaleidoscope. He saw himself playing something different. And it seemed like he wanted to get to that level of playing—I don’t know if it was a dream that came to him, but that’s what he wanted to do. I couldn’t figure out why he wanted me to play with him, because I didn’t feel like, at the time, that I was ready to play with John Coltrane. Being around him was almost, like, “Well, what do you want me to do? I don’t know what I’m supposed to do.”

He always told me, “Play.” That’s what I did.

I loved being around him because I don’t talk that much, either. It was just good vibes between us both. We were just very quiet. All the time that I’d been listening to John, I’m hearing something else, just being around him. He would never start some kind of conversation—he would say something, but it wouldn’t last that long. He never would elaborate, or go deep into it. He said a few words, and that was it. 1

John has influenced me in my playing much longer than I’ve been playing with him, from much before. See, John is the kind of person who is trying to create something different all the time. He has a lot of energy and I learned a lot just from being around him, the way he moves around, things like that. The way John and I play. . it’s different, we’re both natural players and we have our own way of doing things.

Somebody like John is playing things on his horn that make you think a lot of things and he makes me think about doing something in my own way. A person is so involved with himself . . . like John, he’s an older person, like Sonny Rollins, much older than I am and they’ve been playing for a long time.

John knows a lot about music and about his horn and he has a lot of human wisdom. . . and to me, it is like he is trying to make me aware of things by playing his horn…I know that playing with Coltrane has made me much broader in my understanding and my thinking. 2

John plays lines too, but most of the time he will just start playing something, say in D minor, or G minor, and we will go on from there, free. We’re not thinking so much about lines or melodies, just about music. It’s very practical, you know, play right away, without making speeches. When John and I are playing together, it often gets to be more rhythmic. It calls for more rests, some more space. I’m spacing myself more when I’m playing with John. 2

Complement these quotes with John Coltrane in his own words, where he emphasizes how when it comes to music, “the emotional reaction is all that matters“.

Honesty and Self-Expression

I could only retrace myself, to where I first started out and before I started to learn about things, and these have been mostly good ones. Tunes I have written some time ago, I could play them over. What else could I do? Why should I go back and not use all the things I have learned? No, I couldn’t go back to say, Charlie Parker.

What I do now conveys whatever has been done before, and I am trying to put the music beyond all of that. I will never want to play what somebody might be asking me. They either accept what I’m doing, or they should go somewhere else where they can hear what they want to hear. But if somebody listens to me play, he can hear some of my experiences.

Personally, I am trying to be honest with what I am doing. I am trying to live in a peaceful way, and if anybody else can get anything out of my way of living, my way of expressing that state of mind, if they can use it, then that’s good. I’m not trying to convince anybody that what I’m doing is better than what they might be doing, but if we can communicate, we might learn from each other.

And I’m not just talking about music now, just in general. It’s not really about being better these days. It’s about people getting together and trying to make things happen through their spiritual values. It’s not a competitive state of mind anymore. There are still plenty of musicians hung up on that feeling, but they could never play with us. They wouldn’t be comfortable. 2

The Creative and Improvisational Process

Naturally, you have elements of music and musical skills to work with, but once you’ve got those down, I think you should go after feelings. If you try to be too intellectual about it, the music becomes too mechanical. For me, the more I play ‘inside,’ inside the chords and the tune, the more I want to play ‘outside,’ and free. But also, the more I play ‘outside,’ the more I want to play ‘inside’ too. I’m trying to get a balance in my music. A lot of cats play ‘out’ to start with. But if I, myself, start off playing ‘inside’ and then let the spirit take over, wherever it goes, it seems better to me. 6

This idea resonates with jazz pianist Bill Evans, who expressed, “Everything I’ve learned, I’ve learned with feeling being the generating force.”

A lot of time I don’t know what I want to play. So I just start playing, and try to make it right, and make it join to some other kind of feeling in the music. Like, I play one note, maybe that one note might mean love. And then another note might mean something else. Keep on going like that until it develops into—maybe something beautiful. 1

When I play, I try to adjust myself to the group, and I don’t think much about whether the music is conventional or not. If the others go ‘outside,’ play ‘free,’ I go out there too. If I tried to play too differently from the rest of the group, it seems to me I would be taking the other musicians’ energy away from them. I still want to play my own way. But I wouldn’t want to play with anybody that I couldn’t please with the way I play. 7

I just want to start out playing music and see wherever it will go into and let it do what it wants to. I’m not really planning what I’m going to do, as if I would be playing some commercial stuff. I’m just trying to let things happen. But then you need people with you who are able to realize when it starts to happen and who have the mental ability to release that energy you need to create.

You know, in music energy is really nothing but emotion . . . Sometimes when you’re playing with a lot of emotion, the strength becomes the emotion. . I’m still trying to understand that myself . . A lot of things that I do myself, I still don’t know . . well, I know, but I can’t really explain that yet. I can’t put it into words. 2

I’m trying to bring out everything when I play. I might sing a line, go on from there and play, and when I can’t find anything more to play, I’ll sing some more, over and over again, until I feel I have reached something. You know, the music has changed a lot during the last few years. I stopped playing on chord changes some time ago, long before I started playing with Coltrane. They limited me in expressing my feelings and rhythms. I don’t live in chord changes. They’re not expanded enough to hold everything that I live and that comes out in my music.

Just as you can’t really put a time clock on us these days. I don’t feel I can really create any music within a small length of time. Those 30, 40 minute sets in clubs, whatever their system is, that is very restricting and that whole business thing limits your thinking. But most of all, music should always be creative, and it takes a lot of energy to create. That’s really the most important change of all I find. A lot of people just don’t have that kind of energy to give to the music. Or they haven’t learned yet how to release it. 2

Mastering the Art of Tone

It has taken me a relatively long time to get where I am now and I feel that I haven’t even touched on so many things yet. Most of all I have been trying to get a tone…my tone, that seems to be one of the most important things now. The further I shape my tone, towards the way I want it to sound, it will also influence my further musical reactions. Actually, it’s all in the mouthpiece. That is really very important. A lot of people should be working at that much harder.

You should control your mouthpiece completely so that you can get out of the music whatever you want. I might take two notes and make 8 or 9 more notes out of them by putting them into the horn in different ways. Every note has to be shaped. It’s different from just playing a pattern, out of a book or something, but that’s not really being creative. Creativity is purely natural ability. I really couldn’t tell anybody how to do it. You can feel maybe just one note and you give that note so much feeling, as much as you can … and if you overblow it, it begins to go into something else. 2

How To Play Music Creatively

It’s not that I’m trying to play everything so perfect. You need of course a technical ability too, but I am trying to get to a higher state of feeling, of personal emotion. When you need to play a tune, you need technical control, of course. . . but there are a whole lot of people who have their technique very together but still they’re not happening, they’re not really creative. In order to play creatively you have to play good and bad, you have to try and play in as many ways as you can. There are more than just one idea. You just have to have more. . you have to take it as it comes, upside down, crossways. . there are so many things to do. 2

Individuality and Respect

I don’t go around talking to people much, and when I play, I can only be talking to myself, I’m meditating. And they don’t need to listen, really, if they don’t want to. I know for myself, if I go someplace and I don’t like what’s happening, I don’t stay. But if I do like it, I stay and I don’t care about people liking it.

To have respect toward other people and their abilities to hear and observe, you must have respect for yourself and your own abilities. I feel everybody should go their own way and not bother anybody else who wants to do what he likes. If somebody doesn’t want to do what I do, fine, don’t do it, but don’t bother me. 2

Collaboration and Spirituality

I like playing with different people. The ideas of other musicians make me discover different aspects and I can use them my way. There are a lot of people doing things right now. I listen to them. Many times we seem to have the same idea, but really, I’m still learning about so many things. I just try to fit in naturally with whatever is going on. I don’t try to put myself in any kind of bag. But I like to play with musicians who have a spiritual awareness and the creative people who are really trying to do all over again what has already been done. 2

Discipline and Energy

You have to work at that, you know, not only spiritually. You have to watch what you are eating. I eat a lot of natural foods, nuts, cheese, brown rice, and vegetables. That is also part of a personal discipline. People are eating a whole lot of garbage. And I’m studying yoga. The exercises are very good, and it really teaches you to get at your own center, at your own energy, and to combine your spiritual and physical energy. John Coltrane is very concerned with that too. 2

The Meaning Of His Music

I don’t like to talk about what my playing is about. I just like to let it be. If I had to say something, I would say it was about me. About what is. Or about a Supreme Being. 7

A short note

Each Sunday, I share a free email called The Creative Capsule featuring two carefully chosen works: one album and one film.

It’s short, ad-free, and designed to help you decide what to watch or listen to without scrolling.

Related Posts

- “If You’re in the Song, Keep on Playing”: An Interview With Pharoah Sanders, Nathaniel Freidman, New Yorker, 2020

- Pharoah Sanders – A philosophical conversation with Elisabeth van der Mei, Canada’s Coda July Issue Magazine, 1967

- Pharoah Sanders: Jewels of Thought, Jazztimes, 2019

- A Fireside Chat With Pharoah Sanders, All That Jazz

- Pharoah Sanders – The Creator’s Master Plan (Q&A), Pollstar, 2019

- Pharoah’s Tale by Martin Williams, 1968

- Jazz Changes, Martin Williams, 1968

Notes & Sources

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week. Download your free creative reset guide

Download your free creative reset guide