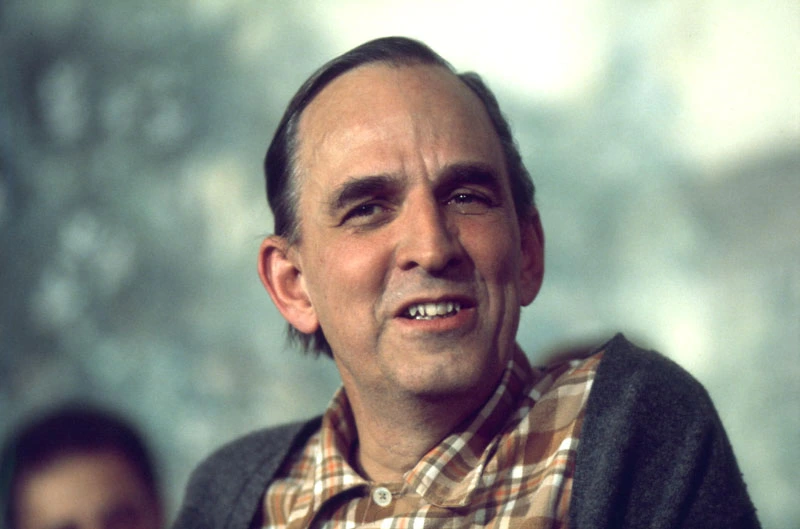

Ingmar Bergman on why you have to have something to say, trusting your intuition, and how to work with actors.

Ingmar Bergman (1918 – 2007) was a Swedish dramatist who probed faith, desire and death in stark chamber pieces. The Seventh Seal’s chess with Death, Persona’s identity bleed and Fanny and Alexander’s family saga forged a language of existential close-ups and Nordic chiaroscuro.

This post is a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with citations found at the end of the article.

Writing Process For Film

The best time in the writing, I think, is when I have no ideas about how to do it. I just play the game. I can lie down on the sofa and can look into the fire. I can go to the seaside and just sit down and do nothing. I just play the game and it’s wonderful. I make some notes, and I can go on for a year.

Then, when I have made a plan the difficult job starts. I have to sit down on my ass every morning at ten o’clock and write the screenplay. Then something very strange happens. Very often the personalities in my scripts don’t want the same thing I want. If I try to force them to do what I want them to do, it will always be an artistic catastrophe. But if I let them free to do what they want and what they tell me, it’s okay. So I think this is the only way to handle it. All intellectual decisions must come afterward. 1

Daily Routine

He followed the same schedule for decades: up at 8am, writing from 9am until noon, then an austere meal. After lunch, Bergman worked from 1pm to 3pm, then slept for an hour. In the late afternoon he went for a walk or took the ferry to a neighbouring island to pick up the newspapers and the mail. In the evening he read, saw friends, screened a movie, or watched TV (he was particularly fond of Dallas). “I never use drugs or alcohol,” Bergman said. “The most I drink is a glass of wine and that makes me incredibly happy.” 2

You Have To Have Something To Say

I think it is a relief to me to know that I have an intention. If I have a passion and an obsession, if I want to tell somebody something and if I want to touch somebody, then film helps me. But if I have nothing to say and I just want to make a film, I don’t make the film.

The craftsmanship of filmmaking is so terribly stimulating, dangerous and obsessing that you can be very tempted. But if you have nothing to come with—this is the most important of all for me—try to be honest with yourself and don’t make the picture.

But if you have something to come with, if you have emotion and passion—a picture in your head, a tension—you can know that even if you aren’t very technical, even if you don’t know where to put the camera, the strange thing is that having worked on the script and having worked with the camera for days and days and the whole time thinking of it, suddenly, when you see the rushes and when you have cut it together, the thing you wanted to tell is there.

I have a very good example and that is Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura. The picture is a mess. He had no idea where to put the camera. He had no money. The actors went away. I think he had enormous problems the whole time.

But he wanted to tell us something about the loneliness of the human being. I can see this picture time after time, and I don’t know what touches me most—how he succeeds without knowing how to do it, or what he wants to say. You have to have something to come with, to give other people. Picture making is some sort of responsibility—that is what I think. 1

The Audience

Making a film comprehensible to the audience is the most important duty of any moviemaker. It’s also the most difficult. Private films are relatively easy to make; but I don’t feel a director should make easy films. He should try to lead his audience a little further in each succeeding film. It’s good for the public to work a little.

But the director should never forget who it is he’s making his film for. In any case, it’s not as important that a person who sees one of my films understands it here, in the head, as it is that he understands it here, in the heart. This is what matters.

I don’t want to make merely intellectual films. I want audiences to feel, to sense my films. This to me is much more important than their understanding them. 3

Why He Made Films

I don’t know anything about messages or symbols or things like that. I am always surprised when people ask me about the message because I just want to get in touch with other human beings and tell them a story when I make a picture. 1

Sponsored: Canvas wall art paintings of nature and the cosmos.

How He Works With Actors

Some people claim I hypnotize my actors—that I use magic to bring the performances out of them that I get. What nonsense! All I do is try to give them the one thing everyone wants, the one thing an actor must have: confidence in himself. That’s all any actor wants, you know. To feel sure enough of himself that he’ll be able to give everything he’s capable of when the director asks for it.

So I surround my actors with an aura of confidence and trust. I talk with them, often not about the scene we’re working on at all, but just to make them feel secure and at ease. If that’s magic, then I am a sorcerer. Then, too, working with the same people—technicians and actors—in our own private world for so many years together has facilitated my task of creating the necessary mood of trust. 3

I just use my intuition. My only instrument is my intuition. When I work at the theater or in the studio with my actors I just feel—as I don’t really know how to handle the situation or how to collaborate with the actors.

One thing is very important to me, that an actor is always a creative human being. What your intuition has to discover is how to make free the creative power. Do you understand what I mean? I can’t explain how it works. It has nothing to do with magic, it has a lot to do with experience.

Some directors work with aggression. The director is aggressive, and the actors are aggressive, and they get marvelous results. But to me this is impossible. I have to be in contact with my actors the whole time, because what we first create when we start a work together is an atmosphere of security around us. And it’s not only me who creates this atmosphere, we create it together. 1

When He Figures Out How To Shoot Scenes

The evening before. When I come home in the evening I just sit down with the script and read the next day’s schedule very carefully. I make up my mind about it and then I just note the choreography of the actors and the camera. Then in the early morning when I meet Sven Nykvist [cinematographer]—you know, we have worked so many years together—in five minutes we go through the scene. I tell him about my ideas for different positions of the camera, for the different positions of the actors and for the atmosphere of the whole scene—and then we can go on the whole day. 1

Where Ideas For His Films Come From

Most of my films have grown from some small incident, a feeling I’ve had about something, an anecdote someone’s told me, perhaps from a gesture or an expression on an actor’s face. It sets off a very special sort of tension in me, immediately recognizable as such to me.

On the deepest level, of course, the ideas for my films come out of the pressures of the spirit; and these pressures vary. But most of my films begin with a specific image or feeling around which my imagination begins slowly to build an elaborate detail.

I file each one away in my mind. Often I even write them down in note form. This way I have a whole series of handy files in my head. Of course, several years may go by before I get around to transforming these sensations into anything as concrete as a scenario.

But when a project begins to take shape, then I dig into one of my mental files for a scene, into another for a character. Sometimes the character I pull out doesn’t get on at all with the other ones in my script, so I have to send him back to his file and look elsewhere. My films grow like a snowball, very gradually from a single flake of snow. In the end, I often can’t see the original flake that started it all. 3

Self-Taught Filmmaker

I’ve had to learn everything about movies by myself. For the theater I studied with a wonderful old man in Göteborg, where I spent four years. He was a hard, difficult man, but he knew the theater, and I learned from him. For the movies, however, there was no one.

Before the war I was a schoolboy, then during the war we got to see no foreign films at all, and by the time it was over I was working hard to support a wife and three children. But fortunately I am by nature an autodidact, one who can teach himself—though it’s an uncomfortable thing to be at times.

Self-taught people sometimes cling too much to the technical side, the sure side, and place technical perfection too high. I think what is important, most important, is having something to say. 3

Trusting Your Intuition

But for all those very difficult decisions—and you have to make hundreds of them every day [on a film set]—I never think. I have to go straight into it and I have to trust my intuition. If you do this, and train yourself not to start making intellectual discussions with your intuition, you are doing the right thing. Only afterward can you think over every step you have made by asking, “What was this? What was that?” 1

Why He Barred Visitors To His Film Sets

Do you know what moviemaking is? Eight hours of hard work each day to get three minutes of film. And during those eight hours there are maybe only ten or twelve minutes, if you’re lucky, of real creation. And maybe they don’t come. Then you have to gear yourself for another eight hours and pray you’re going to get your good ten minutes this time.

Everything and everyone on a movie set must be attuned to finding those minutes of real creativity. You’ve got to keep the actors and yourself in a kind of enchanted circle. An outside presence, even a completely friendly one, is basically alien to the intimate process going on in front of him.

Any time there’s an outsider on the set, we run the risk that part of the actors’ absorption, or the technicians’, or mine, is going to be impinged upon. It takes very little to destroy the delicate mood of total immersion in our work. We can’t risk losing those vital minutes of real creation. The few times I’ve made exceptions I’ve always regretted it. 3

The Opinion Of Film Critics

I’ve given up reading what’s written either about me or about my films. It’s pointless to get annoyed. Most film critics know very little about how a film is made, have very little general film knowledge or culture. But we are beginning to get a new generation of film critics who are sincere and knowledgeable about the cinema. Like some of the young French critics—them I read. I don’t always agree with what they have to say about my films, but at least they’re sincere. Sincerity I like, even when it’s unfavorable to me. 3

Filmmaking & Dreaming

When cinematography is at its best, it is very close to the state of dreaming. You know, in any other art you can’t create a situation that is as close to dreaming. Think only of the time gap. You can make things as long as you want, exactly as in a dream. You can make things as short as you want, exactly as in a dream. As a director, a creator of the picture, you are like a dreamer. You can make what you want. You can construct everything. I think that is one of the most fascinating things that exists. 1

Theater

When I was a teacher in the dramatic school in Sweden, we always started the first class with a discussion of what you need to make theater. On the blackboard we wrote down about a hundred things—stage, actors, tickets, clothes, money, spotlights, footlights, makeup, theater—more than a hundred different things that we thought we needed.

And then I said to them, “Now we take away everything that you think is not necessary.” We went on and went on and went on; we even took away the director. Three things remained.

What we need are actors, a message and an audience. If we have those things we have a performance, because the performance is not here on the stage. It is in the hearts of the audience, and it is very important to know that. 1

Theater fascinates me for several reasons; for one thing, it’s so much less demanding on you than making films. You’re less at the mercy of equipment and the demand for so many minutes of footage every day. You aren’t nearly so alone. It’s between you and the actors, and later on, the audience. It’s wonderful—the sudden meeting of the actor’s expression and the audience’s response. It’s all so direct and alive.

A film, once completed, is inalterable; in the theater you can get a different response from every performance. There’s constant change, always the chance to improve. I don’t think I could live without it. 3

His Camera Style

We have no camera style, Sven and I. What we are interested in is not a style for the camera because the solution of that is in the picture. What we are always interested in is in the light or the shadows, the rhythm in the light and the shadows of the picture. These we discuss a lot and we experiment. 1

Why He Only Made His Films In Sweden

What worries me about making a film in another country is the loss of artistic control I might run into. When I make a film, I must control it from the beginning until it opens in the movie houses. I grew up in Sweden, I have my roots here, and I’m never frustrated professionally here—at least not by producers. I’ve been working with virtually the same people for nearly twenty years; they’ve watched me grow up.

The technical demands of moviemaking are enslaving; but here, everything runs smoothly in human terms: the cameraman, the operator, the head electrician. We all know and understand one another; I hardly need tell them what to do. This is ideal and it makes the creative task—always a difficult one—easier. 3

Compromise

I used to think that compromise in life, as in art, was unthinkable, that the worst thing a man could do was make compromises. But of course I did make compromises. We all do. We have to. We couldn’t live otherwise.

But for a long time I wouldn’t admit to myself—although, of course, at the same time I knew it—that I, too, was a man who compromised. I thought I could be above it all. I have learned that I can’t. I have learned that what matters, really, is being alive. You’re alive; you can’t stand dead or half-dead people, can you? To me, what counts is being able to feel. 3

A short note

Each Sunday, I share a free email called The Creative Capsule featuring two carefully chosen works: one album and one film.

It’s short, ad-free, and designed to help you decide what to watch or listen to without scrolling.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week. Download your free creative reset guide

Download your free creative reset guide