John Updike on first drafts, his writing routine, the purpose of a novel, and his advice to young writers.

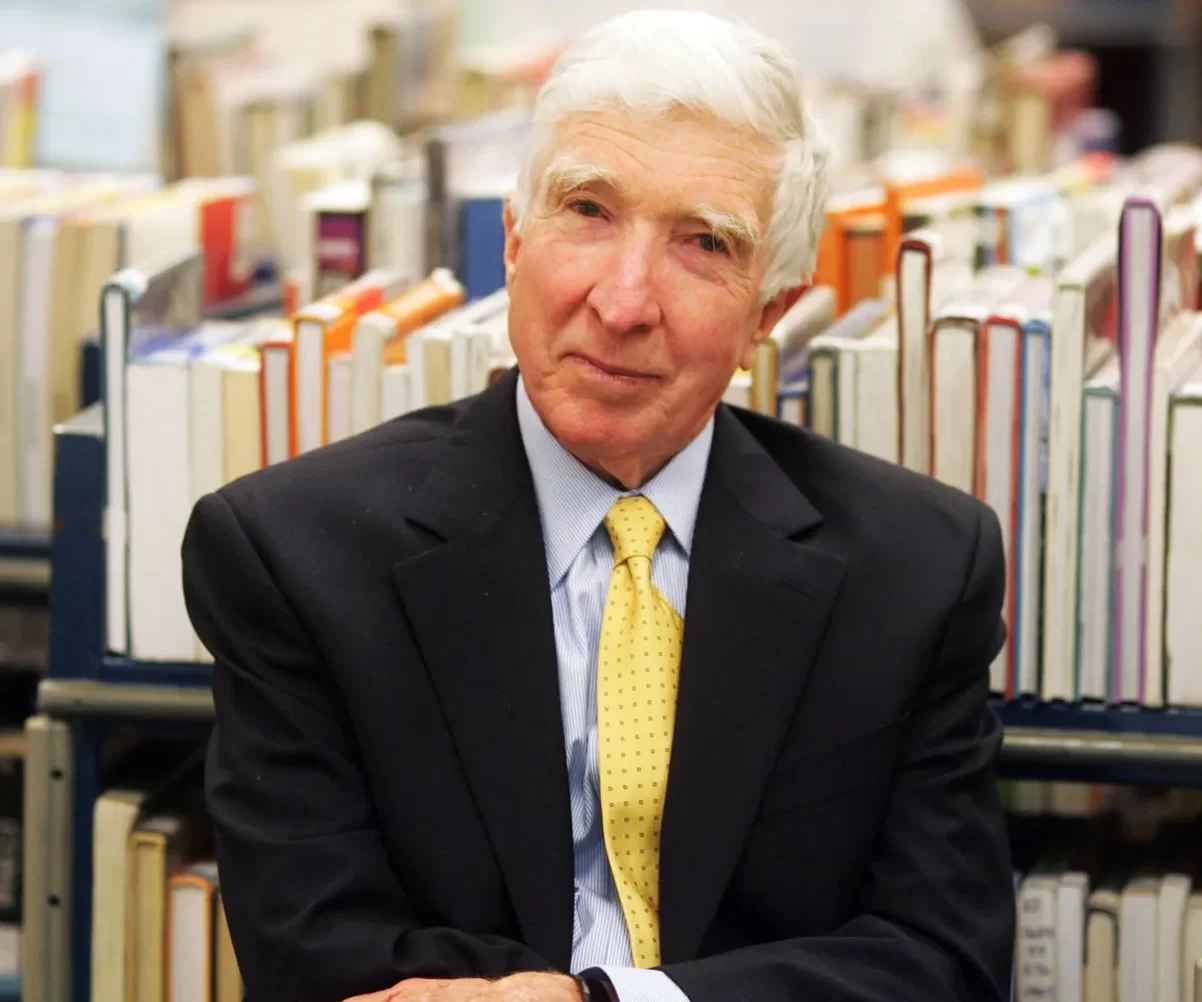

A brief overview of John Updike before delving into his own words:

| Who (Identity) | John Hoyer Updike, an American novelist, short story writer, essayist, and poet, recognized as one of the leading literary figures of the 20th century. He is known for his prolific and versatile writing career. |

| What (Contributions) | Updike’s contributions to literature encompass a wide range of genres, including novels, short stories, poetry, and essays. He is best known for his series of novels featuring the character Rabbit Angstrom, as well as works like “The Witches of Eastwick,” “The Centaur,” and “Couples.” His writing often delved into the complexities of human relationships, suburban life, and the American experience. |

| When (Period of Influence) | Updike’s writing career spanned several decades, from the 1950s until his death in 2009. His works were influential during the mid-to-late 20th century and continue to be studied and appreciated. |

| Where (Geographic Focus) | Born in Reading, Pennsylvania, USA, Updike’s writing often centered on American life and culture, particularly suburban settings. |

| Why (Artistic Philosophy) | Updike’s artistic philosophy involved a keen observation of everyday life and human behavior. He had a fascination with the ordinary, exploring the nuances of interpersonal relationships and the intricacies of the human psyche. |

| How (Technique and Style) | Known for his exquisite prose and detailed descriptions, Updike’s writing style is characterized by its lyrical and precise language. He often blended realism with a touch of symbolism, and his narratives featured introspective characters grappling with the complexities of their lives. |

This post is a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with citations found at the end of the article.

Trust Your Instincts

I think more works of art have been ruined by listening to good advice from other people than by indulging yourself. I do get advice. Of course, I have editors and so on. And sometimes I take it. But in general, I think a writer should have the courage of his own instincts. And believe that the way you wanted to go, and what you wanted to say, is probably the right way to go. 1

Advice To Young Writers

You hesitate to give advice to young writers, because there’s a limit to what you can say. It’s not exactly like being a musician, or even an artist, where there’s a set number of skills that have to be mastered. I marvel at musicians, by the way, that people can play the piano and the violin with that speed and that accuracy. Obviously they need a lot of training. Sometimes writers need no training, and some of the amateur ones who just jump in do better than the ones who have the Ph.D. in creative writing. Colleges are very willing now to teach you, to give you a whole course of creative writing classes. Although I took some when I was a student, I’m a little skeptical about the value.

Try to develop actual work habits, and even though you have a busy life, try to reserve an hour say — or more — a day to write. Some very good things have been written on an hour a day. Henry Greene, one of my pets, was an industrialist actually. He was running a company, and he would come home and write for just an hour in an armchair, and wonderful books were created in this way. So, take it seriously, you know, just set a quota.

Try to think of communicating with some ideal reader somewhere. Try to think of getting into print. Don’t be content just to call yourself a writer and then bitch about the crass publishing world that won’t run your stuff. We’re still a capitalist country, and writing to some degree is a capitalist enterprise, when it’s not a total sin to try to make a living and court an audience.

“Read what excites you,” would be advice, and even if you don’t imitate it you will learn from it. All those mystery novels I read I think did give me some lesson about keeping a plot taut, trying to move forward or make the reader feel that kind of a tension is being achieved, a string is being pulled tight.

Other than that, don’t try to get rich on the other hand. If you want to get rich, you should go into investment banking or being a certain kind of a lawyer. But, on the other hand, I would like to think that in a country this large — and a language even larger — that there ought to be a living in it for somebody who cares, and wants to entertain and instruct a reader. 2

Writing Stylishly

I don’t really think of myself as writing stylishly. I think of myself as trying to write with precision about what my mind’s eye conjures up. So if out of this the sentences become shapely and vivid, that’s great, but I’m really mostly concerned with trying to deliver to the reader my images and my sense of human behavior and of landscape. 3

The Purpose Of A Novel

D.H. Lawrence talks about the purpose of a novel being to extend the reader’s sympathy. And, it is true that upper middle class women can read happily about thugs, about coal miners, about low life, and to some extent they become better people for it because they are entering into these lives that they have never lived and wouldn’t want to lead but nevertheless it is, I think, the sense of possibilities within life. The range of ways to live that in part explains a novel’s value.

I mean, in this day and age, so late really in the life of the genre, why do some of us keep writing them and some of us keep reading them? And I think it is, in part, because of that, that it makes you more human. It’s like meeting people at a cocktail party that you had never met and wouldn’t have cared to meet. You wouldn’t have gone out of your way to meet, but suddenly they become real to you. You understand to some extent. 2

First Drafts & Rewriting

You write your first draft under a certain heat of inspiration. And I think it’s wise not to be too inhibited when you’re putting down that first draft, because you’re basically trying to see the imagined or remembered event. Don’t think too much or you’ll just get stopped and halted.

Rewriting gives the reader a chance to go back and take out repetitions or words that are clearly inexact, or words that are cliches, because cliches come to our mind first. And it’s hard often to know what a cliche exactly is. So my process is to try to write the first draft smoothly, I mean, not rapidly, but steadily. And then you look at it again and you take out everything that would offend you or anybody else. 1

I try to write in my head before I begin, enough so that at least a general shape is there. And I usually put a thing through two versions: the first, whether it’s typewritten or handwritten, and then a cleanly typed version, which I do myself. Some stories or passages are more difficult and demand more fussing with than others, but, in general, I’m a two-draft writer rather than a six-draft writer, or whatever. But the proofs I do take very seriously, as another opportunity to prove and to see with a fresh eye. 4

Writing Routine

The schedule is semi-fixed. I try to write in the morning and then into the afternoon. I’m a later riser; fortunately, my wife is also a late riser. We get up in unison and fight for the newspaper for half an hour. Then I rush into my office around 9:30 and try to put the creative project first. I have a late lunch, and then the rest of the day somehow gets squandered.

There is a great deal of busywork to a writer’s life, as to a professor’s life, a great deal of work that matters only in that, if you don’t do it, your desk becomes very full of papers. So, there is a lot of letter answering and a certain amount of speaking, though I try to keep that at a minimum.

But I’ve never been a night writer, unlike some of my colleagues, and I’ve never believed that one should wait until one is inspired because I think that pleasures of not writing are so great that if you ever start indulging them you will never write again. So, I try to be a regular sort of fellow—much like a dentist drilling his teeth every morning—except Sunday, I don’t work on Sunday, and there are of course some holidays I take.

I should mention something that nobody ever thinks about, but proofreading takes a lot of time. After you write something, there are these proofs that keep coming, and there’s this panicky feeling that this is me and I must make it better. A good deal of time is spent actually rewriting, rereading what you have written. 4

Sponsored: Canvas wall art paintings of nature and the cosmos.

Since I’ve gone through some trouble not to teach and not to have any employment, I have no reason not to go to my desk after breakfast and work there until lunch, so I work three or four hours in the morning. And it’s not all covering blank paper with beautiful phrases… I begin by answering a letter or two — there’s a lot of junk in your life as a writer, most people have junk in their lives — but I try to give about three hours to the project at hand and to move it along. There’s a danger if you don’t move it steadily that you kind of forget what it’s about, so you must keep in touch with it. 2

The Influence Of His Art Abilities On His Writing

I think I try harder to visualize the physical setting. The room, the dress, the face. I’m not sure I always succeed, and there’s a way in which you can suffocate an image under words by putting too many. You know, you can handle, say, “a pale, young lady with arched eyebrows,” but once you start going into the eyebrows hair by hair and do the earrings on top of it, you get sort of no image. You get no image, so you have to watch this tendency to over-specify.

But, I think it is good to — Conrad spoke about helping the reader, making the reader see, see, televise the word, and I think there is that in my writing. A belief that seeing is not quite all, but seeing is a lot of it, and so I hope to see it in my own mind and then to transfer it to the reader’s mind as best I can.

But you know, readers are different and they all have different experiences. “Bed,” the word “bed” means one thing to you, another thing to me, and where I would never have read exactly the word that you would have read yourself, but nevertheless we’re all in the same rough human ballpark here, and I think communication can occur. 2

Where He Got The Idea To Become A Writer

My mother had dreams of being a writer, and I used to see her type in the front room. The front room is also where I would go when I was sick, so I would sit there and watch her. Clearly she was making a heroic effort, and the things would go off in brown envelopes to New York, or Philadelphia even, which had the [Saturday Evening] Post in those years, and they would come back. And so, the notion of it being something that was worth trying and could, indeed, be done with a little postage and effort stuck in my head.

But my real art interest — my real love — was for visual art, and that was what I was better at. It was considered at first. My mother saw that I got drawing lessons and painting lessons. I took what art the high school offered. I went to Harvard still thinking of myself as some kind of potential cartoonist, and I got on the Harvard Lampoon as a cartoonist actually, not as a writer, but the writing maybe was more my cup of tea. There were some very gifted cartoonists over at the Lampoon. And, I saw that maybe there was a ceiling to my cartooning ability, but I didn’t sense the same ceiling for the writing because I had hardly given it a try. By the time I got out of Harvard I think I was determined or pretty much resolved to becoming a writer if I could.

I was prepared to fail. I was prepared to not be able to get things accepted, because I saw that happen to my mother. I knew that not everybody who tried to write actually got published, and in fact that’s kind of a long odds proposition, but I figured I’d give myself five years, and if I couldn’t get into print in five years I should know that I didn’t have what it took. But, as it turned out, I got into print pretty readily. 2

Write What You Know

I’ve not ventured too far from what I could verify with my own eyes. My own life has been my chief window for life in America, beginning with my childhood and the conflicts, the struggles, the strains that I felt in my own family.

I love mystery novels and I’ve tried to write them. When I was in my teens I began to write a mystery novel and tried to figure out how to plot it. You sort of plot it backwards, you know. You know who did it and then you try to hide that, and I couldn’t really do it. I’m not saying I couldn’t do it if a gun was put to my head, but it felt unnatural and felt like a very minor kind of witnessing. In other words, I was willing to be entertained by others, but I didn’t want to write entertainments myself.

I wanted to write books that told everything I knew, that were fully about life in my tame band of it. So quite early I began to try to become a serious writer. It’s a little puzzling. I’ve written some science fiction. That may not be well-known, but a couple of my novels are located in a hypothetical future. There is something about it that frees you up in a way. Your attempt is always to write about the world you know, but also to somehow get out of it, if only by a little jump or a trick. Something must be different so that your imagination is really engaged. You’re not just spilling your life, but you’re to some extent inventing another life.

If you can’t base your fiction upon ordinary people and the issues that engage them, then you are reduced to writing about spectacular unreal people. You know, James Bond or something, and you cook up adventures. The trick about fiction, as I see it, is to make an unadventurous circumstance seem adventurous, to make it excite the reader, either with its truth or with the fact that there’s always a little more that goes on, and there’s multiple levels of reality. As we walk through even a boring day, we see an awful lot and feel an awful lot. To try to say some of that seems more worthy than cooking up thrillers. 2

His Personal Rules For Literary Criticism

1. Try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt.

2. Give enough direct quotation—at least one extended passage—of the book’s prose so the review’s reader can form his own impression, can get his own taste.

3. Confirm your description of the book with quotation from the book, if only phrase-long, rather than proceeding by fuzzy précis.

4. Go easy on plot summary, and do not give away the ending.

5. If the book is judged deficient, cite a successful example along the same lines, from the author’s œuvre or elsewhere. Try to understand the failure. Sure it’s his and not yours?

To these concrete five might be added a vaguer sixth, having to do with maintaining a chemical purity in the reaction between product and appraiser. Do not accept for review a book you are predisposed to dislike, or committed by friendship to like. Do not imagine yourself a caretaker of any tradition, an enforcer of any party standards, a warrior in any ideological battle, a corrections officer of any kind.

Never, never … try to put the author “in his place,” making of him a pawn in a contest with other reviewers. Review the book, not the reputation. Submit to whatever spell, weak or strong, is being cast. Better to praise and share than blame and ban. The communion between reviewer and his public is based upon the presumption of certain possible joys of reading, and all our discriminations should curve toward that end. 5

Writing In A Linear Way

I’m a fairly linear writer. I read other writers, both living and dead, who write in patches and hop about from what seems to them a scene they can envision and then they work backwards. But to me that doesn’t produce a good novel. Although some good novels have been written that way.

I begin with the beginning and the end in mind and the general curve of the middle. And of course, you’re going to be surprised and disappointed as you go along. Some scenes don’t materialize, others do and so on. You obviously can’t pre plan everything. But I think if you don’t know the ending, how are you going to give the book that shape in the readers mind that it should have? In other words, you have toin some way see it as a thing in your mind with a beginning, middle and end. 1

Influences

Writers who have moved me to the point that I wish to emulate them vary from James Thurber, the humorist, to Proust, to Italo Calvino, to Nabokov, actually, whom I discovered by myself, kind of, and who amazed me and still amazes me: the man really tried to make language do several things at once. I think it’s nice since we have limited time—it’s nice to read a page that is truly intricately worked. It rewards attention. So much doesn’t reward attention; you wish you could read it faster.

In the American vein, I think I am pretty ragged in my education. I continue to be greatly moved by Hawthorne, who seemed to me to have the American shyness and limitedness, and yet a sort of beautiful man talking, a beautiful sense of breathing. I’m not doing it quite right, but I was amazed by “The Scarlet Letter,” and what a good woman this was. American fiction does not have many good women in it. Melville, I think, is a writer I admire for his wit, his ambitiousness, and again for something very masculine.

Recently, I found myself giving a lecture on Whitman and very much enjoying reading the early poems. I think he began to repeat himself, but this is a common American disease. Among moderns, I’m in the opposition of seeming to prefer Hemingway to Faulkner, perhaps because I haven’t read enough Faulkner. But I find that Faulkner, even in his best novels, just goes on too long and has something kind of uncontrolled. I found that the people who by and large really enjoy Faulkner are fellow Southerners and, since I’m not a Southerner, I seem to be outside the club of ardent Faulkner lovers. But, all these men are not great names for nothing.

Dreiser, I think, is another writer who, at least in his early books, really grabbed the bull by the right horns somehow. He has a wonderful ease of a frontal attack on a situation. He cut through a lot of sludge and I think that’s one of the perennial artistic problems—to cut through sludge, cut through the accretions of tradition and of convention and see freshly what the living reality is.

So, I try to be alert to the masterpieces or even the semi-masterpieces that exist; on the other hand, I’m different from those men, my times are different. To a large extent, we have to make our way alone, and often by lesser stars. That is, I think we’re often influenced by a lesser writer who happens to catch at something we need than by a greater writer who doesn’t. 4

The Role Of An Editor

An editor can sometimes suggest things that you might do without, but an editor can very rarely suggest putting something in. An editor is not a creative function. What my editors have done for me basically has been to cheer me on and encourage me and make me feel like this wasn’t terribly quixotic, and in a way, luxuriant enterprise.

The editor is your link to the real world in a way, because the editor then takes a piece of work from your trembling and innocent hand and passes it on to the iron hands of the printer, the salesman, and eventually the public. So an editor is kind of a midwife. Editors should not attempt to write the book, but maybe when they have a strongly negative reaction, they should register it. Otherwise encourage the poor, the poor author. 1

How He Would Like To Be Remembered

As a person who was not ashamed of American life and tried to live it and look at it as clearly as he could, and also who tried to make something beautiful out of the descriptions of it, who tried to lift the ordinary into the eternal realm of art. 1

Sunday Museletter (Free)

Ignite your creativity with hand-picked weekly recommendations in music, film, books, and art — sent straight to your inbox every Sunday.

Next up: Rainer Maria Rilke on Courage.

References

- John Updike: To Be a Novelist, YouTube

- John Updike Interview With The Academy of Achievement, 2004

- Arts: A Conversation with John Updike | The New York Times, YouTube

- ‘American Centaur‘, Književna Smotra, 1979

- Remembering Updike: The Gospel According to John“, The New Yorker online

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.