Bill Evans on the universal musical mind, technique, the creative process in jazz, simplicity, and the piano as a gateway to music.

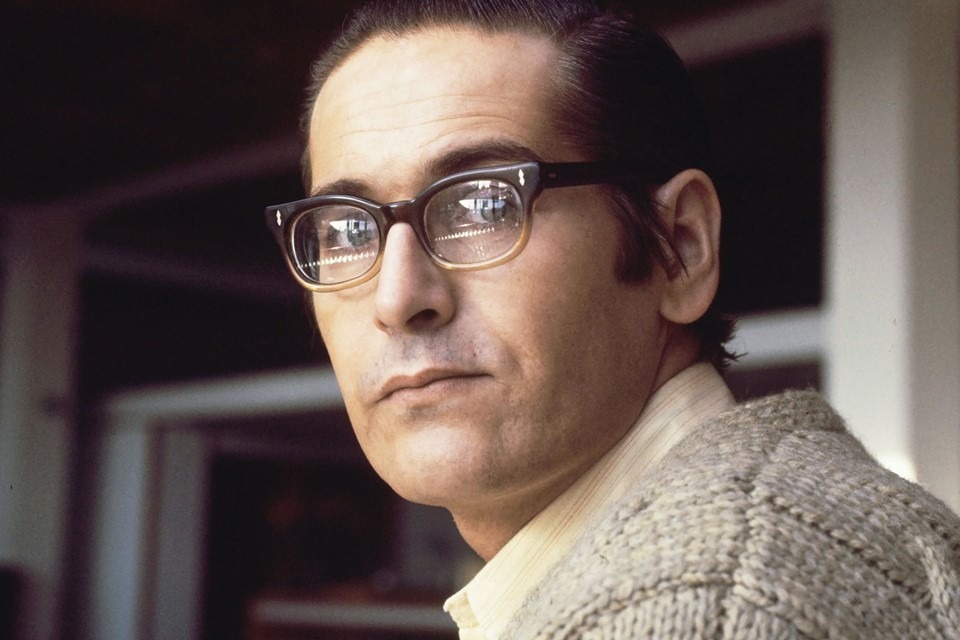

A brief overview of Bill Evans before delving into his own words:

| Who (Identity) | William John Evans, known as Bill Evans, an American jazz pianist and composer, celebrated for his innovative contributions to jazz music. |

| What (Contributions) | Bill Evans is renowned for his harmonic richness and innovative use of chord voicings, improvisation, and rhythmic interplay. His work has significantly influenced jazz piano and the development of modal jazz. Notable albums include “Sunday at the Village Vanguard,” “Waltz for Debby,” and “Portrait in Jazz.” |

| When (Period of Influence) | Evans was active in the music industry from the 1950s until his death in 1980. His career spanned three decades, during which he significantly impacted jazz music and its evolution. |

| Where (Geographic Focus) | Born in Plainfield, New Jersey, USA, Evans’ career was primarily centered in the United States, with a strong presence in the New York jazz scene. |

| Why (Artistic Philosophy) | Evans’ approach to music was characterized by a deep emotional expression and a quest for lyrical improvisation. His style blended classical influences with jazz harmonies, focusing on melodic invention and subtle interplay between musicians. |

| How (Technique and Style) | Bill Evans is known for his distinctive, impressionistic approach to jazz piano, marked by nuanced touch, complex chords, and innovative interpretations of jazz standards. He favored a collaborative trio format, which allowed for intimate, interactive musical conversations. |

This post is a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with citations found at the end of the article.

Feeling

Everything I’ve learned, I’ve learned with feeling being the generating force. I’ve never approached the piano as a thing in itself, but as a gateway to music. 1

Universal Musical Mind

I believe that all people are in possession of what might be called a universal musical mind. Any true music speaks with this universal mind to the universal mind in all people.

The understanding that results will vary only in so far as people have or have not been conditioned to the various styles of music in which the Universal Mind speaks.

Consequently, often some effort and exposure is necessary in order to understand some of the music coming from a different period or a different culture than that to which the listener has been conditioned. 2

Simplicity

It’s better to do something simple, which is real. It can still be satisfactory, but it’s something you can build on because you know what you’re doing. Whereas if you try to approximate something, which is very advanced, and don’t know what you’re doing, you can’t advance that, build on it. 2

The simple things, the essences, are the great things, but our way of expressing them can be incredibly complex. It’s the same thing with technique in music. You try to express a simple emotion — love, excitement, sadness — and often your technique gets in the way.

It becomes an end in itself when it should really be only the funnel through which your feelings and ideas are communicated. The great artist gets right to the heart of the matter. 3

Technique

Technique is the ability to translate your ideas into sound through your instrument. This is a comprehensive technique which goes beyond scales and so on. It’s expressive technique … a feeling for the keyboard that will allow you to transfer any emotional utterance into it. What has to happen is that you develop a comprehensive technique and then say, ‘Forget that. I’m just going to be expressive through the piano.’

You have to spend a lot of years at the keyboard before what’s inside can get through your hands and into the piano. For years and years that was a constant frustration for me. I wanted to get that expressive thing in, but somehow it didn’t happen.

When I was about twenty-six, that was the first time I had attained a certain degree of expressiveness in my playing. Believe me, I had played a lot of jazz before then. I started when I was thirteen. I was putting some of the feelings I had into the piano. Of course, having the feelings is another thing, another matter.” 4

His Development As A Musician

I started studying piano when I was six, but this was classical music. At the ages six to thirteen, I acquired the ability to sight read and to play classical music. So that actually, both of us {him and his brother Harry} as you know, were performing Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and so on, intelligently, musically. But yet, I couldn’t play My Country, ‘Tis of Thee without the notes.

Now, this is a fine thing to be able to play a masterpiece, intelligently, musically, and still not to be able to be creative and understand music enough to be able to play a simple thing like My Country, ‘Tis of Thee without having the music in front of you.

One night I got real adventurous {playing with a rehearsal band when he was younger} and I put in a little note that wasn’t written, and this was such an experience to make music that wasn’t that indicated. That really got me into starting to want to think about how to make the music.

I learned mostly on the job, and then I started to learn about changes in harmonics and how a tune was built harmonically, so that I could remember the harmony and be able to play without music. And be able to substitute one harmony for another or to change the harmonies and so on.

The whole process of learning to play jazz is to take these problems from the outer level and one by one to stay with them at a very intense conscious concentration level, until that process becomes secondary and subconscious.

Now, when that becomes subconscious, then you can begin concentrating on that next problem, which will allow you to do a little bit more, and so on, and so on. It wasn’t until I was 28, or something like that, that I began to feel a degree of expressive ability, the ability to now write out my feelings freely through some sort of a craft. That might give you an idea of how the problem is approached and what degree of time and effort is necessary to make all of this subconscious so that you can then express yourself. And I would certainly say more than worth it.

I can remember having coming to New York to make my break in jazz, and saying to myself now how should I attack this practical problem of becoming a jazz musician and making a living? And I said, well, ultimately, I came to the conclusion that all I must do is take care of the music, even if I do it in a closet. And if I really do that somebody is going to come and open the door of the closet and say, hey, we’re looking for you. This is the way I really approached the whole thing.

If I spread myself all over the place, I would have lost sight of everything. It’s like you say isn’t terrible there’s a war here and starvation and poverty. And now what am I going to do as a human being about this whole thing? Well, gosh, if you try to accept every problem, you’re just going to go insane.

So you have to choose some field in which you operate at your best capacity and which will then serve as an influence to deter all these other things. So I figured if I take care of the music as best I can with my truest beliefs, then all these other things will be affected as I desire them to be affected, as much as I can affect them. 2

Understand The Problem & Enjoy The Process

People tend to approximate the product, rather than attacking it in a realistic, true way at any elementary level – regardless of how elementary – but it must be entirely true and entirely real and entirely accurate. They would rather approximate the entire problem, then to take a small part of it and be real and true about it.

To approximate the whole thing in a vague way gives you a feeling that you’ve more or less touched the thing, but in this way you just lead yourself toward confusion, and ultimately you’re going to get so confused that you’ll never find your way out.

But it is true of any subject that the person that succeeds in anything, has the realistic viewpoint at the beginning and knows that the problem is large, and that he had to take it a step at a time and he has to enjoy the step by step learning procedure.

I think most people just don’t realize the immensity of the problem and and either, because they can’t conquer it immediately, think that they haven’t got the ability, or they’re so impatient to conquer it that they never do see it through. But if you do understand the problem, I think then you can enjoy your whole trip through. 2

Improvising

It’s very important to remember that no matter how far I might diverge or find freedom in this format [improvising while playing jazz music], that it only is free insofar as it has reference to the strictness of the original form. And that’s what gives it its strength.

In other words, there is no freedom without being in reference to something. If you take this form, and you find some way to get away from it, that gives it a meaning. 2

Reading

Evans loved to read, in particular humorous books, Thomas Hardy, and philosophy. His bookcases held works by Plato, Voltaire, Whitehead, and Santayana, as well as Freud, Margaret Mead, Sartre, and Thomas Merton.

He had introduced John Coltrane to the works of the Southern Indian spiritual leader and philosopher Krishnamurti. Middle and Far Eastern religions held a fascination for him, including Islam and Zen. 1

Sponsored: Canvas wall art paintings of nature and the cosmos.

How He Learned From Other Musicians

You see, you learn from everyone. From Nat King Cole I’d take rhythm and sparsity; from Dave Brubeck a particular voicing; from George Shearing also a voicing, but of another kind; from Oscar Peterson a powerful swing; from Earl Hines a sense of structure.

Bud Powell has it all, but even from him I wouldn’t take everything. I wouldn’t listen to a recording by Bud and try to play along with it, to imitate. Rather, I’d listen to the record and try to absorb the essence of it and apply it to something else.

Besides, it wasn’t only the pianists but also the saxophones, the trumpets, everybody. It’s more the mind “that thinks jazz” than the instrument “that plays jazz” that interests me. 5

Teaching Jazz

When you begin to teach jazz, the most dangerous thing is that you tend to teach style. The one time I attempted to teach was at Lenox at the jazz school, and I had 11 piano students. And I would say eight of them, didn’t even want to know about chords or anything, they didn’t want to do anything that anybody had ever done, because they didn’t want to be imitators, you know?

Well, of course, this is pretty naive, and an attempt to circumvent great problems of music. But nevertheless, it does bring to light the fact that if you’re going to try to teach jazz, you must try to teach principles which are separate from style, you must abstract the principles of music, which have nothing to do with style, and this is exceedingly difficult. 2

Allow the Idea To Express Itself

There is a Japanese visual art in which the artist is forced to be spontaneous. He must paint on a thin stretched parchment with a special brush and black water paint in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible.

These artists must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.

This conviction that direct deed is the most meaningful reflection, I believe, has prompted the evolution of the extremely severe and unique disciplines of the jazz or improvising musician. 6

Musical Influences

“I can remember, for instance, the 78 album of Petruschka which I got

early on in high school as a Christmas present-a requested Christmas present. And just about wearing it out, learning it. That was the kind of music that at that time I hadn’t been exposed to, and it just was a tremendous experience to get into that piece. I remember first hearing some of Milhaud’s polytonality and actually a piece that he may not think too much of- it was an early piece called Suite Provencale – which opened me up to certain things. 1

I was buying all the records … anybody from Coleman Hawkins to Bud Powell and Dexter Gordon. That was when I first heard Bud, on those Dexter Gordon sides on Savoy. I heard Earl Hines very early and, of course, the King Cole Trio. 7

On Nat King Cole:

Nat, I thought, was one of the greatest, and I still do. I think he is probably the most underrated jazz pianist in the history of jazz. 7

{On his pianism} one of the tastiest and just swingin’est and beautifully melodic improvisers and jazz pianists that jazz has ever known, and he was one of the very first that really grabbed me hard. 1

Classical Music:

The list of classical musicians Bill was influenced by is endless, but here are some he has mentioned: Mozart, Schumann, Rachmaninoff, Ravel, Gershwin, Villa-Lobos, Khachaturian, Milhaud, Chopin. Also a quote from Jean-Louis Ginibre’s interview with Bill: “Bach, Brahms, Debussy, Beethoven, Bartok, Stravinsky.”

Opinion Of The Layman

I do not agree that the layman’s opinion is less of a valid judgment of music than that of the professional musician. In fact, I would often rely more on the judgment of a sensitive layman than that of a professional sense of professional because of his constant involvement with the mechanics of music must fight to preserve the naivety that the layman already possesses. 2

Jazz

Jazz, as we we tend to look at it, is a style. But I feel that jazz is not so much a style as a process of making music. It’s the process of making one minute’s music in one minute’s time. Whereas when you compose, you could make one minute music and take three months to compose one minutes music. Now that’s the only basic difference.

Jazz is more of a certain creative process of spontaneity than a style. Therefore, you might say that Chopin or Bach or Mozart, or whoever improvised music, that is was able to make music of the moment, was in a sense, playing jazz. That’s the way I feel about it in an absolute sense.

I would like to say that one of the most thrilling things about jazz as a spontaneous creative process is, for instance, in recording it, and later hearing oneself and being so surprised at what has happened.

Any good teacher of composition will always tell the student that the composition should sound as if it’s improvised, it should have a spontaneous quality. So actually, the the art of music is the art of speaking with this spontaneous quality. And that is a thrilling part of jazz in that it has more or less resurrected the art of spontaneous creative music. 2

Music Must Say Something

The fact that music is polytonal, atonal, polyrhythmic or whatever doesn’t bother me – but it must say something. I work with very simple means because I’m a simple person, and I came from a simple tradition out of dance music and jobbing, and though I’ve sorta studied a lot of other music, I feel that I know my limitations and I try to work within them.

Really, there’s no limit to the expression I could make within the idiom if I had the inner need to say something. This is where I find the problem. More an emotional, a creative-emotional problem. 1

Sunday Museletter (Free)

Ignite your creativity with hand-picked weekly recommendations in music, film, books, and art — sent straight to your inbox every Sunday.

Next up: Stanley Kubrick on directing.

References

- Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings, Peter Pettinger

- The Universal Mind of Bill Evans: Jazz Pianist On The Creative Process And Self-Teaching

- Bill Evans – Intellect, Emotion, Communication – By Don Nelsen

- The Great Jazz Pianists: Speaking Of Their Lives And Music, by Lyons Len

- Bill Evans – Time Remembered: An Interview by Jean-Louis Ginibre

- Bill Evans, liner note to Kind of Blue

- DeMicheal, Bill Evans Plays.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.