Elia Kazan on directing actors, valuing cinematographers, what makes a director, screenwriting tips, and working with producers.

A brief overview of Elia Kazan before delving into his own words:

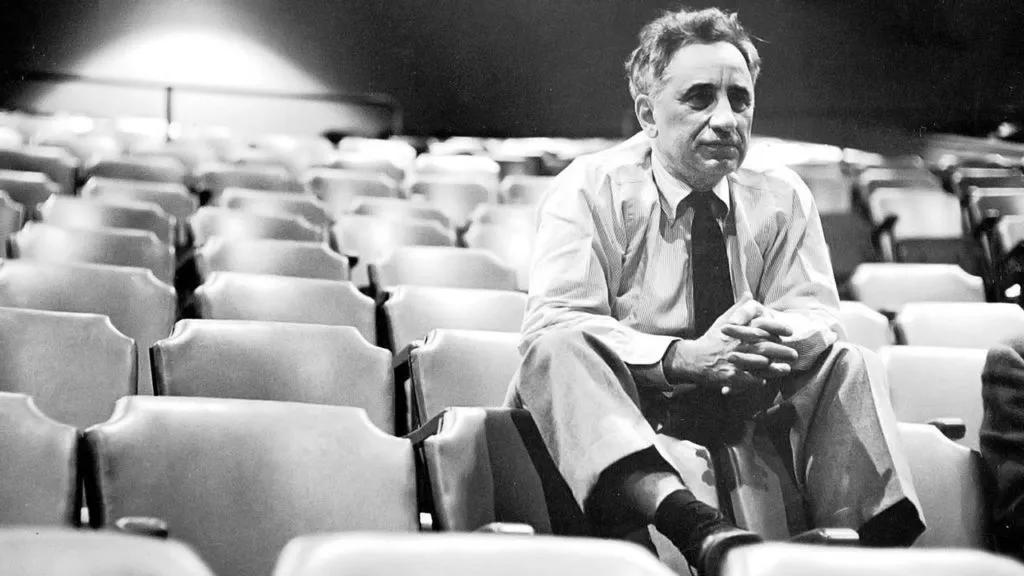

| Who (Identity) | Elia Kazan was an American film and theatre director, producer, screenwriter, and actor. He was a key figure in the post-war American theatre and cinema, with his works often reflecting and challenging the morals of contemporary society. |

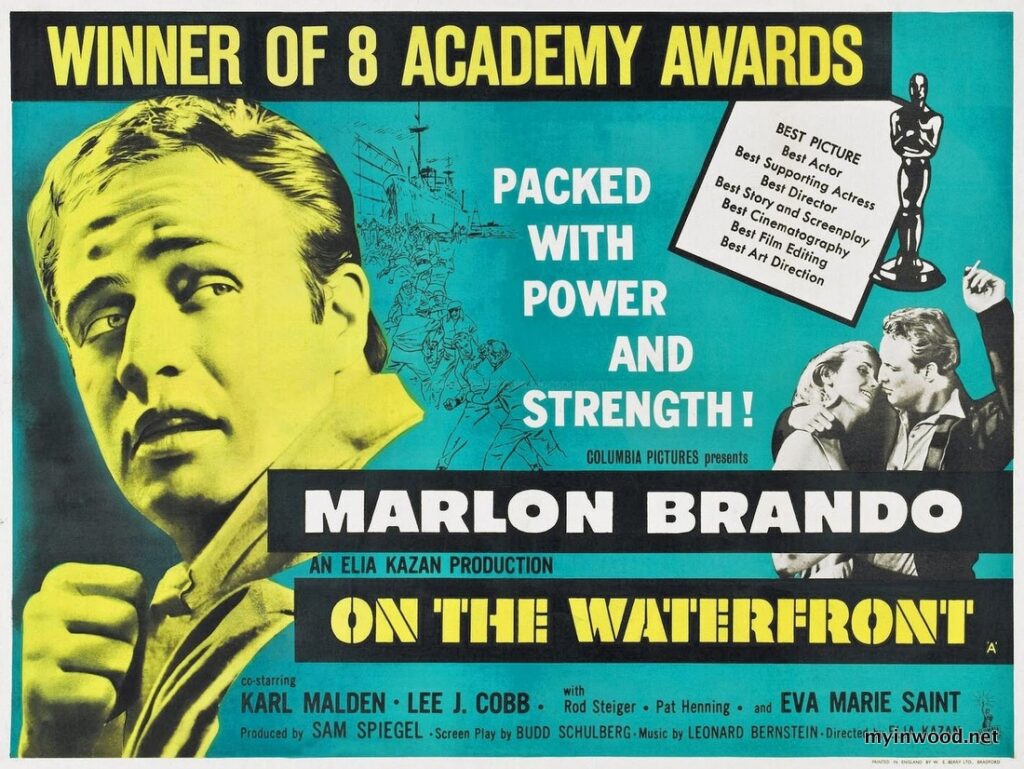

| What (Contributions) | Kazan is renowned for directing critically acclaimed films such as “A Streetcar Named Desire,” “On the Waterfront,” and “East of Eden.” He was instrumental in the development of method acting within Hollywood, working closely with actors to extract profound performance depth. His films are known for their emotional intensity and complex, morally ambiguous characters. |

| When (Period of Influence) | Kazan’s influence was most prominent in the mid-20th century, particularly during the 1940s to the 1960s. His films and theatrical productions during this era not only reflected the tensions of the times but also pushed the boundaries of storytelling and actor-director collaboration. |

| Where (Geographic Focus) | Though a Turkish immigrant, Kazan’s works primarily focus on American life, exploring themes of identity, morality, and the American dream. His narratives are often set against quintessentially American backdrops, from the urban landscapes of New York City to rural America, reflecting the diverse socio-economic environments of the United States. |

| Why (Artistic Philosophy) | Elia Kazan’s artistic philosophy revolved around the exploration of personal and societal conflicts. He aimed to craft stories that questioned traditional values and provoked thought about personal responsibility, integrity, and the societal pressures that influence human behavior. His direction encouraged actors to delve deeply into their characters, bringing an unprecedented level of realism and psychological depth to the screen. |

| How (Technique and Style) | Kazan’s technique and style were characterized by his use of method acting, a technique he honed during his time with the Actors Studio. He emphasized naturalistic performances and deep psychological exploration. His cinematic style often included tight framing and a close focus on characters, which intensified the dramatic tension and highlighted the inner turmoil of his characters. |

This post is a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with citations found at the end of the article.

Screenwriting

Keep A Diary

Keep a diary. It will force you to articulate your observations, and it will train your eyes and ears to see and hear and notice. Carry a pocket notebook. Always have a pen with you. A half-hour’s walk can be valuable. Every street in New York can provide an encounter, and all encounters that surprise you are precious. A bus or subway ride can be a treasure trip. Don’t take taxis. You see nothing and learn nothing in a taxi—it’s a waste of time. 1

Understanding Playwriting and Screenwriting

A director should know everything about playwriting and/or screenplay writing, even if he is unable to write, is incapable of producing anything worth putting before an audience. He must be able to see the merits but also anticipate the problems involved in producing a script. The director is responsible for the script. Its faults are his responsibility. There is no evading this. He is there to guide the playwright to correct whatever faults the script has. At the same time, he must respect the merits of the playwright’s work during the tensions of production. He is responsible for the protection of the manuscript.

Note that the word is not “playwrite,” it’s “playwright.” A play for the theatre is made as much as it is written. A film is made, not written. They are both constructions. The construction tells the story more than the words. In the movies, the director should be co-author (ideally) because that is what inevitably he is. He should work on the screenplay with the writer from the very beginning. The manner in which the story is developed tells more than the words do. 1

Sponsored: Canvas wall art paintings of nature and the cosmos.

Screenwriting: More Architecture Than Literature

The problems that arise during production are almost always problems of construction. Since so much of the story of a film is told by visual images, the director is the co-creator. A screenplay is not literature—a film is constructed of pieces of film joined together during the editing process. The most memorable films are not usually treasured for their literary values. But in film as well as in works for the stage, story construction is a major component.

A filmscript is more architecture than literature. This will get my friends who are writers mad, but it’s the truth: The director tells the movie story more than the man who writes the dialogue. The director is the final author, which is the reason so many writers now want to become directors. It’s all one piece. Many of the best films ever made can be seen without dialogue and be perfectly understood. The director tells the essential story with pictures. Dialogue, in most cases, is the gravy on the meat. It can be a tremendous “plus,” but it rarely is. Acting, the art, helps; that too is the director’s work. He finds the experience within the actor that makes his or her face and body come alive and so creates the photographs he needs. Pictures, shots, angles, images, “cuts,” poetic long shots—these are his vocabulary. Not talk. What speaks to the eye is the director’s vocabulary, his “tools,” just as words are the author’s.

A true artistic partnership between a writer and a filmmaker is an excellent solution, but it’s rarely arrived at. The dialogue remains an adjunct to the film rather than its central element. What can be told through images, through movement, through the expressiveness of the actor, what can be told without explicit and limiting dialogue, is best done that way. Reliance on the visual allows the ambiguity, the openness of life. 1

Some of you may have heard of the auteur theory. That concept is partly a critic’s plaything. Something for them to spat over and use to fill a column. But it has its point, and that point is simply that the director is the true author of the film. The director TELLS the film, using a vocabulary, the lesser part of which is an arrangement of words.

A screenplay’s worth has to be measured less by its language than by its architecture and how that dramatizes the theme. A screenplay, we directors soon enough learn, is not a piece of writing as much as it is a construction. We learn to feel for the skeleton under the skin of words.

Meyerhold, the great Russian stage director, said that words were the decoration on the skirts of action. He was talking about Theatre, but I’ve always thought his observations applied more aptly to film. 2

Writing For Film: Rules And Tips

The subject of writing for the theatre or screen defies easily formulated rules. The best rule of screen and play writing was given to me by John Howard Lawson, a onetime friend. It’s simple: unity from climax. Everything should build to the climax. But all I know about script preparation urges me to make no rules, although there are some hints, tools of the trade, that have been useful for me. One of these is “Have your central character in every scene.” This is a way of ensuring unity to the work and keeping the focus sharp. Another is: “Look for the contradictions in every character, especially in your heroes and villains. No one should be what they first seem to be. Surprise the audience.”

It is essential that the viewer be able to follow the flow of events. If you keep trying to figure out who is who and where it’s all happening and what is going on, you can’t emotionally respond to what’s being shown to you. But keep in mind that the greatest quality of a work of art may be its ability to surprise you, to make you wonder.

Another rule I have found useful is: Every time you make a cut, you improve a scene. Somerset Maugham, a wise old man, said that there are two important rules of playwriting. “One, stick to the subject. Two, cut wherever you can.” Another wise man said: “If it occurs to you that something might be cut, it should be cut.” Paul Osborn, an experienced and smart playwright and screenwriter, invited me to a screening of a movie made by the producer Sam Goldwyn. Sam asked Paul his opinion. “Needs cutting,” said Paul. This made Sam frantic because he thought the same but didn’t know what to do about it. “But where?” he asked. Paul answered, “Everywhere.” 1

Embracing The Unexpected

One of the purposes of improvisation—and it’s just as important in film as in theatre—is to free the wild impulses of people. It opens the possibility of surprises. It allows actors to surprise themselves.

Within each person is the life of the unexpected. A good writer will surprise us, and that arouses our interest and challenges us and awakens our sense of truth. The surprise is the thing. Play for it. Fuck up if you have to. Surprise yourself! A surprise will throw the movement off kilter, off the proper condition. And “proper” is a dangerous word in art—it has to be thrown out, and something beyond and altered has to be invited in. The great writers, the great actors, the great artists have the capability and even the practice of surprising us. They open the door to the unexpected.

Or another time when you began to laugh and couldn’t stop, and you didn’t really know why you found what was making you laugh so overwhelmingly funny. What is the opposite? Good sense. Control. Civilization. And in the case of preparation for a play, adherence to the lines, saying them meaningfully and not overdoing the suggestion of feeling apparently called for by the text. Good sense, when it takes over, is deadly. 1

Cinematography

Valuing the Cameraman’s Role

In my film work, the collaborators I valued most were the cameramen. Since I came from the theatre, where the spoken word is so essential, I had to be jolted into realizing that the eye, not the ear, was the most important sense, that a film’s story is told by a sequence of images, and that very often, the less dialogue there is the better, that if a film could be told entirely by pictures, that would be best of all. I was forced to learn this lesson straight off in my very first film, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. There I experienced the essential shock. My cameraman was a grumpy fellow whom I came to love. His name was Leon Shamroy, and his nickname with the crew was “Grumble-gut.”

He immediately set back the cocky young fellow from the New York stage (me) by arriving for work every morning with only the vaguest acquaintance with the text for that day’s work.

“What’s the garbage for today?” he’d ask in his rasping voice.

“Why the hell didn’t you read the script?” I’d come back.

“I’d rather watch a rehearsal,” he’d say. “That will tell the story.”

I soon came to see that his point of view, while extreme, was essentially the correct one, that I should photograph behavior, not “talking heads.” With this realization in mind, I began to study the work of the great directors. I marveled at how long Jack Ford would hold a long shot and how much it would tell, what imagination and daring he had. Watching his work and that of other directors I admired, I realized that all I’d been doing was photographing action of a kind that predominates the stage, staying mostly in medium shots with a close-up now and then to “punch home” a point or make an emphasis. In every difficulty, I’d rely on the spoken word rather than a revealing image.

So the cameramen became my friends in California. I thought most producers ignorant, inept bluffers. I thought the same of many directors, noting how heavily they relied on their cameramen to tell them where to put the camera down and what to do with it. Also, despite my reputation as an “actors’ director,” I did not find most actors stimulating artistic collaborators. There were exceptions, but if I were to choose a generalization that would be true to me, I’d say that my allegiance shifted from words to the camera and to the cameramen. I felt that, even more than the director, they were “on the spot,” they had to produce a piece of film every day that would be used in the final picture. They had to make good, as we say, and no excuse would be accepted.

The thing I like most about cameramen is a human quality: They actually enjoy the job of making a film, the work itself. Producers worry and wait for the end of shooting, sometimes to see if they can take the editing process away from the director. So they reveal themselves to be the director’s enemy. Actors worry about their performance, whether it’s a step forward or backward in the agent-market. Screenwriters sweat with fear, often believing that a director is lousing up their script. But the cameramen I’ve known and their crews come to work with joy; they come to “play.” They’re the men for me. Where a producer resents rain and smoke and snow and the movement of the clouds over the sun because they delay production, cameramen love these events of nature. Extreme cold or a burning sun makes an actor look less like an actor and more like an ordinary human being. 1

Costume Design

His Approach To Costuming

The first step in costuming is analysis of character and, even before that, defining the central motivation of the script and determining the style of the production to convey the intent of the work. Costuming must be a function of the whole, it must work in tandem with all the other visual elements. There are very few productions, as I see it, that should be realistic. And I doubt there is any such thing as “realistic.” The instant a choice is made, it is subjective; the costume reflects the director’s analysis of the character, which will be a personal, unique, and idiosyncratic view.

Start at the bottom. Study what people wear on the street. Remind yourself that they are “costumed;” their clothes were chosen to make a certain impression. Think of no apparel as casually chosen, as “innocent.” Think of it as functioning in a situation, one that you can only guess, or imagine, or make up. Think of it as worn for a purpose. This may be as simple as keeping out the cold or the rain. But within the practicality there is choice. 1

Actors

How To Direct Actors

One of the most important things in an acting scene, especially a short acting scene, is not to talk about the scene that precedes but to play out the scene that precedes. You play out where the actors have come from psychologically so their ride into a scene is a correct one.

Once you’ve done that, you divide the scene—or I tend to—into sections, into movements. Stanislavsky called them “beats.” The point is that there are sections in life. Sometimes even a short scene has a three-act structure. You lay bare the actor, you make him understand and appreciate the structure beneath the lines. That’s what’s called the subtext, and dealing with the subtext is one of the critical elements in directing actors. In other words, not what is said, but what happens.

In general, actors or actresses must have the art in the accumulation of their past. Their life’s experience is the director’s material. They can have all the training, all the techniques their teachers have taught them—private moments, improvisations, substitutions, associative memories, and so on—but if the precious material is not within them, the director cannot get it out. That is why it’s so important for the director to have an intimate acquaintance with the people he casts in his plays. If it’s “there,” he has a chance of putting it on the screen or on the stage. If not, not.

That is why the practice of making an actor read the lines of a part has no value for me and can even be misleading. The best line readers, I’ve learned, are not the best actors for my films, which is why I take actors for a walk or for dinner and probe into their lives. That is especially easy to do with actresses. Women are easily led to reveal to anyone who seems to be a friend the secrets of their intimate lives; it is their most essential drama. 1

I saw a lot of brilliant guys in the theater when I was stage manager making great speeches. They should have published the speeches instead of putting the show on. Directors show off a lot, it’s a terrible thing. If you could direct a whole movie without a word of direction, you’d be better off because then the actors would be doing it spontaneously. Sometimes (…) I didn’t do anything. I read once, but then that scene is so good, the personal intentions in it are so clear, and the actors so gifted, that I did nothing. The actors knew it all. It’s so human and so basic. 3

When I had very experienced actors (…), I gave them the basic overall objective and then each day reaffirmed it in relation to the scene that was played that day. 3

Actor And Director Relationship

Does a director ‘fall’ for members of his cast? Of course he does. How could it be otherwise? The director is on the most intimate terms with, a participant in the life experience of, each person involved with him in the effort. Even the most mechanical side of the work will relate to a fundamental choice of meaning and feeling. As to whether the director and the leading lady will fall in love, well, it’s inevitable. How could it be otherwise? It is a relationship where everything is at stake and nothing can be concealed.

The wise partners of the actor and director will expect this and understand and not resent whatever develops. The partner can be sure of one thing. The relationship between director and player will not last. What caused it to happen was the mutual effort to excel at any cost. And when the enterprise is completed, the effort will drain away and disappear. But while it goes on, the fact is this: My fate is in your hands, your fate in mine.

Nothing else, no other way of working on a project in art, is worth the time or the trouble. Totality, nothing held back, passion undiminished from beginning to end! And that is the pleasure of it. 1

Key Qualities Of A Good Actor

Everyone asks about acting. It’s not a stupid question. Everyone wants to know what makes a good actor; what makes a good director. No one asks these questions more often–and for longer periods of time–than actors or directors.

And no one has a definitive answer. The answer varies. The more you learn, the more you fail, the longer you live, the more the answers to things vary.

No one can teach anyone to act or to direct: An existing talent is only made stronger and clearer and smarter. So many people I could name came to me with extraordinary talents and instincts, and absolutely no clear idea how to utilize anything with which they had been gifted. A good director doesn’t tell an actor how wrong they are, or how muddled. A good director is like the good friend my father was: A friend of his was depressed, in a bad way. Almost everyone told him to buck up, snap out of it, but my father only told him how much he missed his good friend, the real man trapped in whatever sadness had consumed him. My father’s friend improved.

You do the same with any artist–actor, writer, designer: You remind them of what they have and what they’ve done and what they can do. You keep shining light on the path they’re taking, and you occasionally help them with the heavy load they’ve taken on.

If a director is smart, he admits that good actors are ahead of him on the path: I always play catch-up, playing a sort of relay race with their talents. I race toward them and try to help them make it to the end. Great talents–a Brando or a De Niro–are far ahead of me, almost to the finish line, but I can tell them what they did in the race. Or I try to.

A good actor is intelligent in a rustic, basic, almost feral way: He or she has been observing people in various behaviors for a lifetime, noticing how they operate, how they think, how they take in information. Almost all good actors are recessive, shy. In an audition or a meeting, you can see the way their eyes move and their hands work, and you instantly recognize the child they were and the artist they’re becoming. They are always studying, taking things in.

Some actors aren’t really artists, aren’t really good, but they have a quality, a look, that is ideal for a particular part. At that point the director merely keeps them in line and heading toward a goal, a performance, that is right for the material. Some actors receive acclaim for one of these performances, and then people wonder why they never repeated the goodness they once had. Well, it was used up for that one ideal performance. If they’re lucky, they will build a career on cleverly sustaining and repeating that one, effective performance. You know who these people are. They serve a purpose; they have been useful. Just don’t ever confuse them for a real actor, a real artist.

A good director or a good actor or a good writer–for film or theatre–has to have the capacity to love fully and messily; to really give of himself. A great deal of patience is required, and a rigorous maintenance of your mind and your body. You have to be alert. You have to be present.

The best performances–of all artists–have been loved into existence. 4

Producers

Working With Producers

All kinds of brilliant ideas, not those of the person who made the film, sprout in executive offices. Discussions are held between the producer and his agent, his wife, the money men, and sometimes even the stars, all in an effort to “save” the film, which means having the film make as much money as possible. These spurts of wisdom are the result of anxiety and nerves and have little to do with the filmmaker’s original intentions. Everybody has good ideas in this anxious, dangerous time, a time when good ideas are not the point. The point is to realize the original intention of the filmmaker.

A great film cannot be made by consensus. In the late 1920s and 1930s—the first great period of American films—it was the unquestioned right of the major directors to cut their own films. They developed the shooting script with the writers. But by the time I got to Hollywood in the mid-1940s, the power was shifting. The industry was increasingly dominated by producers. Everyone at MGM served the wishes of the elite producers, and these producers did everything upside down as far as I was concerned—they bought the novels and plays, commissioned original screenplays, oversaw the writers, and when they had what would pass for a shooting script, they found the director. The director of course should have come first, for he is the one to enforce unity of intention. For David O. Selznick, producing was not enough: No matter what the credit lines read, in the end he directed and edited the movie and wrote the screenplay—if the photographer or director didn’t do as he dictated, he fired them.

Today it is the people who put up the money who decide its use. They have turned an art into an industry, and the director into merely one of many functionaries. That is how these men will it, because in that contest they can rule everyone working on the film and they can supervise every choice. They select the film editor who, in most cases, becomes their servant. If they don’t like what the film editor does, they replace him with another who is more pliable. They select the cameraman, and often they demand that he make the film as “pretty” as possible, with candy colors and clear definitions of all events no matter what the director was trying to create. Mood is a curse word to them.

It’s a question of power. Nothing less. Don’t give anyone the power to distort what you’re making. If it’s a choice of control or money, take less money. You’re better off. “Produced and Directed” is what you want. It’s the only correct principle. Of course, a director needs staff help: set, office, financial assistants, and managers. And someone has to raise the money, enough money so that you can make the movie you want, but it’s better to slim the budget than to concede power to a producer. You must be the boss, however quietly you speak, however gentle your smile, however agreeable your manners.

I’ve had all types of producers. When asked to direct a completed script by a producer, I had to remind myself (and once stifled the thought with tragic consequences) that the producer will own the film you make and do what he wants with your work. At the start, he will be a gracious host (his specialty, often), promising to give you a free hand. (No matter what he says, get an astute lawyer to read the contract.) But in the end, when a serious difference arises (and all differences as the work nears the end are serious), he will win. You are just an employee. You both talked a good game, but the fact remains that he owns the negative, and he’ll do what he thinks necessary. He’ll have good reasons and bring in respected witnesses (who agree with him, of course) to back him, and you will find yourself powerless.

So when you’re looking for money, if a producer shows up promising what you need in exchange for ultimate control, cut your needs, find another way, reduce the budget. Generally, the more money you take for your services, the less power you’ll have. Take less than what you deserve; make the film on a smaller budget. Gamble on profit. The job itself is a gamble. If the film makes money, you will be well compensated; if not, you won’t be living with the shame of having sold yourself to someone who doesn’t share your aims. 1

Directing

A Director Has To Be Arrogant

Avoid being a nice guy, a decent guy, a conforming guy—stifle him. The portrait I am painting of the director is a vision of a completely arrogant man. It is an accurate and necessary portrait. Everyone around you will try to soften you. Show no shame when you’re accused of being arrogant. Say what you think no matter whom it might offend. You’re not about to guide a children’s summer camp. More likely you are related to a zoo-keeper. You need to have supreme confidence in the purpose, the intent, the content, the importance of your undertaking. Anyone who helps is a friend, everyone else an enemy who has to be won over. But if you can’t, fuck them.

Remember that everyone has to bow to you and heed your every wish. They should. Without that degree of arrogance there will be chaos. 1

What Makes A Director

Below is an address Kazan delivered at Wesleyan University on the occasion of a retrospective of his fims, September 1973.

It might be fun if I were to try to list for you and for my own sport what a film director needs to know as what personal characteristics and attributes he might advantageously possess.

How must he educate himself?

Of what skills is his craft made?

Of course, I’m talking about a book-length subject. Stay easy, I’m not going to read a book to you tonight. I will merely try to list the fields of knowledge necessary to him, and later those personal qualities he might happily possess, give them to you as one might give chapter headings, section leads, first sentences of paragraphs, without elaboration.

Here we go.

Literature. Of course. All periods, all languages, all forms. Naturally a film director is better equipped if he’s well read. Jack Ford, who introduced himself with the words, “I make Westerns,” was an extremely well and widely read man.

The Literature of the Theatre. For one thing, so the film director will appreciate the difference from film. He should also study the classic theatre literature for construction, for exposition of theme, for the means of characterization, for dramatic poetry, for the elements of unity, especially that unity created by pointing to climax and then for climax as the essential and final embodiment of the theme.

The Craft of Screen Dramaturgy. Every director, even in those rare instances when he doesn’t work with a writer or two – Fellini works with a squadron – must take responsibility for the screenplay. He has not only to guide rewriting but to eliminate what’s unnecessary, cover faults, appreciate nonverbal possibilities, ensure correct structure, have a sense of screen time, how much will elapse, in what places, for what purposes. Robert Frost’s Tell Everything a Little Faster applies to all expositional parts. In the climaxes, time is unrealistically extended, “stretched,”usually by clasps.

The film director knows that beneath the surface of his screenplay there is a subtext, a calendar of intentions and feelings and inner events. What appears to be happening, he soon learns, is rarely what is happening. This subtext is one of the film director’s most valuable tools. It is what he directs. You will rarely see a veteran director holding a script as he works – or even looking at it. Beginners, yes.

Most directors’ goal today is to write their own scripts. But that is our oldest tradition. Chaplin would hear that Griffith Park had been flooded by a heavy rainfall. Packing his crew, his stand-by actors and his equipment in a few cars, he would rush there, making up the story of the two reel comedy en route, the details on the spot.

The director of films should know comedy as well as drama. Jack Ford used to call most parts “comics.” He meant, I suppose, a way of looking at people without false sentiment, through an objectivity that deflated false heroics and undercut self-favoring and finally revealed a saving humor in the most tense moments. The Human Comedy, another Frenchman called it. The fact that Billy Wilder is always amusing doesn’t make his films less serious.

Quite simply, the screen director must know either by training or by instinct how to feed a joke and how to score with it, how to anticipate and protect laughs. He might well study Chaplin and the other great two reel comedy-makers for what are called sight gags, non-verbal laughs, amusement derived from “business,” stunts and moves, and simply from funny faces and odd bodies. This vulgar foundation – the banana peel and the custard pie – are basic to our craft and part of its health. Wyler and Stevens began by making two reel comedies, and I seem to remember Capra did, too.

American film directors would do well to know our vaudeville traditions.

Just as Fellini adored the clowns, music hall performers, and the circuses of his country and paid them homage again and again in his work, our filmmaker would do well to study magic. I believe some of the wonderful cuts in Citizen Kane came from the fact that Welles was a practicing magician and so understood the drama of sudden unexpected appearances and the startling change. Think, too, of Bergman, how often he uses magicians and sleight of hand.

The director should know opera, its effects and its absurdities, a subject in which Bernardo Bertolucci is schooled. He should know the American musical stage and its tradition, but even more important, the great American musical films. He must not look down on these; we love them for very good reasons.Our man should know acrobatics, the art of juggling and tumbling, the techniques of the wry comic song. The techniques of the Commedia dell’arte are used, it seems to me, in a film called 0 Lucky Man! Lindsay Anderson’s master, Bertolt Brecht, adored the Berlin satirical cabaret of his time and adapted their techniques.

Let’s move faster because it’s endless.

Painting and Sculpture; their history, their revolutions and counter revolutions. The painters of the Italian Renaissance used their mistresses as models for the Madonna, so who can blame a film director for using his girlfriend in a leading role – unless she does a bad job.

Many painters have worked in the Theatre. Bakst, Picasso, Aronson and Matisse come to mind. More will. Here, we are still with Disney.

Which brings us to Dance. In my opinion, it’s a considerable asset if the director’s knowledge here is not only theoretical but practical and personal. Dance is an essential part of a screen director’s education. It’s a great advantage for him if he can “move.” It will help him not only to move actors but move the camera. The film director, ideally, should be as able as a choreographer, quite literally .So I don’t mean the tango in Bertolucci’s Last or the High School gym dance in American Graffiti as much as I do the baffle scenes in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation which are pure choreography and very beautiful. Look at Ford’s Cavalry charges that way. Or Jim Cagney’s dance of death on the long steps in The Roaring Twenties.

The film director must know music, classic, so called-too much of an umbrella word, that! Let us say of all periods. And as with sculpture and painting, he must know what social situations and currents the music came out of.

Of course he must be particularly INTO the music of his own day – acid rock; latin rock; blues and jazz; pop; tin pan alley; barbershop; corn; country; Chicago; New Orleans; Nashville.

The film director should know the history of stage scenery, its development from background to environment and so to the settings INSIDE WHICH films are played out. Notice I stress INSIDE WHICH as opposed to IN FRONT OF. The construction of scenery for filmmaking was traditionally the work of architects. The film director must study from life, from newspaper clippings and from his own photographs, dramatic environments and particularly how they affect behavior.

I recommend to every young director that he start his own collection of clippings and photographs and, if he’s able, his own sketches.

The film director must know costuming, its history through all periods, its techniques and what it can be as expression. Again, life is a prime source. We learn to study, as we enter each place, each room, how the people there have chosen to present themselves. “How he comes on,” we say.

Costuming in films is so expressive a means that it is inevitably the basic choice of the director. Visconti is brilliant here. So is Bergman in a more modest vein. The best way to study this again is to notice how people dress as an expression of what they wish to gain from any occasion, what their intention is. Study your husband, study your wife, how their attire is an expression of each day’s mood and hope, their good days, their days of low confidence, their time of stress and how it shows in clothing.

Lighting. Of course. The various natural effects, the cross light of morning, the heavy flat top light of midday – avoid it except for an effect – the magic hour, so called by cameramen, dusk. How do they affect mood? Obvious. We know it in life. How do they affect behavior? Study that. Five o’clock is a low time, let’s have a drink! Directors choose the time of day for certain scenes with these expressive values in mind. The master here is Jack Ford who used to plan his shots within a sequence to best use certain natural effects that he could not create but could very advantageously wait for. Colors? Their psychological effect. So obvious I will not expand. Favorite colors. Faded colors. The living grays. In Baby Doll you saw a master cameraman – Boris Kaufman – making great use of white on white, to help describe the washed out Southern whites.

And, of course, there are the instruments which catch all and should dramatize all; the tools the director speaks through, the CAMERA and the TAPE RECORDER. The film director obviously must know the Camera and its lenses, which lens creates which effect, which one lies, which one tells the cruel truth. Which filters bring out the clouds. The director must know the various speeds at which the camera can roll and especially the effects of small variations in speed. He must also know the various camera mountings, the cranes and the dollies and the possible moves he can make, the configurations in space through which he can pass this instrument. He must know the zoom well enough so he won’t use it or almost never.

He should be intimately acquainted with the tape recorder. Andy Warhol carries one everywhere he goes. Practice “bugging” yourself and your friends. Notice how often speech overlaps.

The film director must understand the weather, how it’s made and where, how it moves, its warning signs, its crises, the kind of clouds and what they mean. Remember the clouds in Shane. He must know weather as dramatic expression, be on the alert to capitalize on changes in weather as one of his means. He must study how heat and cold, rain and snow, a soft breeze, a driving wind affect people and whether it’s true that there are more expressions of group rage during a long hot summer and why.

The film director should know the City, ancient and modern, but particularly his city, the one he loves like DeSica loves Naples, Fellini-Rimini, Bergman-his island, Ray Calcutta, Renoir-the French countryside, Clair-the city of Paris. His city, its features, its operation, its substructure, its scenes behind the scenes, its functionaries, its police, firefighters, garbage collectors, post office workers, commuters and what they ride, its cathedrals and its whore houses.

The film directors must know the country – no, that’s too general a term. He must know the mountains and the plains, the deserts of our great Southwest, the heavy oily, bottom – soil of the Delta, the hills of New England. He must know the water off Marblehead and Old Orchard Beach, too cold for lingering and the water off the Florida Keys which invites dawdling. Again, these are means of expression that he has and among them he, must make his choices. He must know how a breeze from a fan can animate a dead-looking set by stirring a curtain.

He must know the sea, first-hand, chance a ship wreck so he’ll appreciate its power. He must know under the surface of the sea; it may occur to him, if he does to play a scene there. He must have crossed our rivers and know the strength of their currents. He must have swum in our lakes and caught fish in our streams. You think I’m exaggerating. Why did old man Flaherty and his Mrs. spend at least a year in an environment before they exposed a foot of negative? While you’re young, you aspiring directors, hitch-hike our country! And topography, the various trees, flowers, ground cover, grasses. And the subsurface, shale, sand, gravel, New England ledge, six feet of old river bottom? What kind of man works each and how does it affect him?

Animals, too. How they resemble human beings. How to direct a chicken to enter a room on cue. I had that problem once and I’m ashamed to tell you how I did it. What a cat might mean to a love scene. The symbolism of horses. The family life of the lion, how tender! The patience of a cow.

Of course, the film director should know acting, its history and its techniques. The more he knows about acting, the more at ease he will be with actors. At one period of his growth, he should force himself on stage or before the camera so he knows this experientially, too. Some directors, and very famous ones, still fear actors instead of embracing them as comrades in a task. But, by contrast, there is the great Jean Renoir, see him in Rules of the Game. And his follower and lover, Truffaut in The Wild Child, now in Day for Night.

The director must know how to stimulate, even inspire the actor. Needless to say, he must also know how to make an actor seem NOT to act. How to put him or her at their ease, bring them to that state of relaxation where their creative faculties are released.

The film director must understand the instrument known as the VOICE. He must also know SPEECH. And that they are not the same, as different as resonance and phrasing. He should also know the various regional accents of his country and what they tell about character.

All in all he must know enough in all these areas so his actors trust him completely. This is often achieved by giving the impression that any task he asks of them, he can perform, perhaps even better than they can. This may not be true, but it’s not a bad impression to create.

The film director, of course, must be up on the psychology of behavior, “normal” and abnormal. He must know that they are linked, that one is often the extension or intensification of the other and that under certain stresses which the director will create within a scene as it’s acted out, one kind of behavior can be seen becoming the other. And that is drama.

The film director must be prepared by knowledge and training to handle neurotics. Why? Because most actors are. Perhaps all. What makes it doubly interesting is that the film director often is. Stanley Kubrick won’t get on a plane – well, maybe that isn’t so neurotic. But we are all delicately balanced – isn’t that a nice way to put it? Answer this: how many interesting people have you met who are not – a little?

Of course we work with the psychology of the audience. We know it differs from that of its individual members. In cutting films great comedy directors like Hawks and Preston Sturges allow for the group reactions they expect from the audience, they play on these. Hitchcock has made this his art.

The film director must be learned in the erotic arts. The best way here is through personal experience. But there is a history here, an artistic technique. Pornography is not looked down upon. The film director will admit to a natural interest in how other people do it. Boredom, cruelty, banality are the only sins. Our man, for instance, might study the Chinese erotic prints and those scenes on Greek vases of the Golden Age which museum curators hide.

Of course, the film director must be an authority, even an expert on the various attitudes of lovemaking, the postures and intertwining of the parts of the body, the expressive parts and those generally considered less expressive. He may well have, like Bunuel with feet, special fetishes. He is not concerned to hide these, rather he will probably express his inclinations with relish.

The director, here, may come to believe that suggestion is more erotic than show. Then study how to go about it.

Then there is war. Its weapons, its techniques, its machinery, its tactics, its history – oh my – Where is the time to learn all this?

Do not think, as you were brought up to think, that education starts at six and stops at twenty-one, that we learn only from teachers, books and classes. For us that is the least of it. The life of a film director is a totality and he learns as he lives. Everything is pertinent, there is nothing irrelevant or trivial. 0 Lucky Man, to have such a profession! Every experience leaves its residue of knowledge behind. Every book we read applies to us. Everything we see and hear, if we like it, we steal it. Nothing is irrelevant. It all belongs to us.

So history becomes a living subject, full of dramatic characters, not a bore about treaties and battles. Religion is fascinating as a kind of poetry expressing fear and loneliness and hope. The film director reads The Golden Bough because sympathetic magic and superstition interest him, these beliefs, of the ancients and the savages parallel those of his own time’s people. He studies ritual because ritual as a source of stage and screen mise-en-scene is an increasingly important source.

Economics a bore? Not to us. Consider the demoralization of people in a labor pool, the panic in currency, the reliance of a nation on imports and the leverage this gives the country supplying the needed imports. All these affect or can affect the characters and milieus with which our film is concerned. Consider the facts behind the drama of On the Waterfront. Wonder how we could have shown more of them.

The film director doesn’t just eat. He studies food. He knows the meals of all nations and how they’re served, how consumed, what the variations of taste are, the effect of the food, food as a soporific, food as an aphrodisiac, as a means of expression of character. Remember the scene in Tom Jones? La Grande Bouffe?

And, of course, the film director tries to keep up with the flow of life around him, the contemporary issues, who’s pressuring whom, who’s winning, who’s losing, how pressure shows in the politician’s body and face and gestures. Inevitably, the director will be a visitor at night court. And he will not duck jury duty. He studies advertising and goes to “product meetings” and spies on those who make the ads that influence people. He watches talk shows and marvels how Jackie Susann peddles it.

He keeps up on the moves, as near as he can read them, of the secret underground societies. And skyjacking, what’s the solution? He talks to pilots. It’s the perfect drama – that situation – no exit.

Travel. Yes. As much as he can. Let’s not get into that.

Sports? The best directed shows on TV today are the professional football games. Why? Study them. You are shown not only the game from far and middle distance and close-up, you are shown the bench, the way the two coaches sweat it out, the rejected sub, Craig Morton, waiting for Staubach to be hurt and Woodall, does he really like Namath? Johnson, Snead? Watch the spectators, too. Think how you might direct certain scenes playing with a ball, or swimming or sailing – even though that is nowhere indicated in the script. Or watch a ball game like Hepburn and Tracy in George Steven’s film, Woman of the Year!

I’ve undoubtedly left out a great number of things and what I’ve left out is significant, no doubt, and describes some of my own shortcomings.

Oh! Of course, I’ve left out the most important thing. The subject the film director must know most about, know best of all, see in the greatest detail and in the most pitiless light with the greatest appreciation of the ambivalences at play is – what?

Right. Himself.

There is something of himself, after all, in every character he properly creates. He understands people truly through understanding himself truly.

The silent confessions he makes to himself are the greatest source of wisdom he has. And of tolerance for others. And for love, even that. There is the admission of hatred to awareness and its relief through understanding and a kind of resolution in brotherhood.

What kind of person must a film director train himself to be?

What qualities does he need? Here are a few:

A white hunter leading a safari into dangerous and unknown country;

A construction gang foreman, who knows his physical problems and their solutions and is ready, therefore, to insist on these solutions;

A psychoanalyst who keeps a patient functioning despite intolerable tensions and stresses, both professional and personal;

A hypnotist, who works with the unconscious to achieve his ends;

A poet, a poet of the camera, able both to capture the decisive moment of Cartier Bresson or to wait all day like Paul Strand for a single shot which he makes with a bulky camera fixed on a tripod;

An outfielder for his legs. The director stands much of the day, dares not get tired, so he has strong legs. Think back and remember how the old time directors dramatized themselves. By puttees, right.

The cunning of a trader in a Baghdad bazaar.

The firmness of an animal trainer. Obvious. Tigers!

A great host. At a sign from him fine food and heartwarming drink appear.

The kindness of an old-fashioned mother who forgives all.

The authority and sternness of her husband, the father, who forgives nothing, expects obedience without question, brooks no nonsense.

These alternatively.

The illusiveness of a jewel thief – no explanation, take my word for this one.

The blarney of a PR man, especially useful when the director is out in a strange and hostile location as I have many times been.

A very thick skin.

A very sensitive soul.

Simultaneously.

The patience, the persistence, the fortitude of a saint, the appreciation of pain, a taste for self-sacrifice, everything for the cause.

Cheeriness, jokes, playfulness, alternating with sternness, unwavering firmness. Pure doggedness.

An unwavering refusal to take less than he thinks right out of a scene, a performer, a co-worker, a member of his staff, himself.

Direction, finally, is the exertion of your will over other people, disguise it, gentle it, but that is the hard fact.

Above all – COURAGE. Courage, said Winston Churchill, is the greatest virtue; it makes all the others possible.

One final thing. The ability to say “I am wrong,” or ‘I was wrong.” Not as easy as it sounds. But in many situations, these three words, honestly spoken will save the day. They are the words, very often, that the actors struggling to give the director what he wants, most need to hear from him. Those words, “I was wrong, let’s try it another way,” the ability to say them can be a life-saver.

The director must accept the blame for everything. If the script stinks, he should have worked harder with the writers or himself before shooting. If the actor fails, the director failed him! Or made a mistake in choosing him. If the camera work is uninspired, whose idea was it to engage that cameraman? Or choose those set-ups? Even a costume after all – the director passed on it. The settings. The music, even the goddamn ads, why didn’t he yell louder if he didn’t like them? The director was there, wasn’t he? Yes, he was there! He’s always there!

That’s why he gets all that money, to stand there, on that mound, unprotected, letting everybody shoot at him and deflecting the mortal fire from all the others who work

with him.The other people who work on a film can hide. They have the director to hide behind.

And people deny the auteur theory!

After listening to me so patiently you have a perfect right now to ask, “Oh, come on, aren’t you exaggerating to make some kind of point?”

But only a little exaggerating.

The fact is that a director from the moment a phone call gets him out of bed in the morning (“Rain today. What scene do you want to shoot?”) until he escapes into the dark at the end of shooting to face, alone, the next days problems, is called upon to answer an unrelenting string of questions, to make decision after decision in one after another of the fields I’ve listed. That’s what a director is, the man with the answers.

Watch Truffaut playing Truffaut in Day for Night, watch him as he patiently, carefully, sometimes thoughtfully, other times very quickly, answers questions. You will see better than I can tell you how these answers keep his film going. Truffaut has caught our life on the set perfectly.

Do things get easier and simpler as you get older and have accumulated some or all of this savvy? Not at all. The opposite. The more a director knows, the more he’s aware how many different ways there are to do every film, every scene.

And the more he has to face that final awful limitation, not of knowledge but of character. Which is what? The final limitation and the most terrible one is the limitations of his own talent. You find, for instance, that you truly do have the faults of your virtues. And that limitation, you can’t do much about. Even if you have the time.

One last postscript. The director, that miserable son of a bitch, as often as not these days has to get out and promote the dollars and the pounds, scrounge for the liras, francs and marks, hock his family’s home, his wife’s jewels, and his own future so he can make his film. This process of raising the wherewithal inevitably takes ten to a hundred times longer than making the film itself. But the director does it because he has t~who else will? Who else loves the film that much?

So, my friends, you’ve seen how much you have to know and what kind of a bastard you have to be. How hard you have to train yourself and in how many different ways. All of which I did. I’ve never stopped trying to educate myself and to improve myself.

So now pin me to the wall – this is your last chance. Ask me how with all that knowledge and all that wisdom, and all that training and all those capabilities, including the strong legs of a major league outfielder, how did I manage to mess up some of the films I’ve directed so badly?

Ah, but that’s the charm of it!” 2

Total Responsibility in Filmmaking

There is only one way of looking at this trade: The filmmaker is responsible for everything. To rephrase that thought: Everything is your fault, and only rarely will you be praised for anything. But face it, if something goes wrong with your work, you the filmmaker (director), who fought for total control, as we all do, should not have allowed it to happen. If you’re going to work in films, you must straight off accept total responsibility.

Final and absolute responsibility? That is not only a heavy obligation, but it is just the way we want it. It’s not a burden, it’s the rule of the game as we choose to play it. Making a film is an exercise in total control. My advice and my warning to people starting out in this field is to not surrender authority to anyone. Don’t be nice, don’t be cooperative, don’t be obliging. Be sweet-tempered, of course, cordial, sure, pick up the checks and send flowers to the wife of your star, why not, but don’t give in where it counts, not ever—and it counts, as I hope you’ll see, in every area of the job. 1

Commitment and Self-Reflection in Directing

A director commits himself to a project twice. The first time is from spontaneous enthusiasm. The second is after asking questions and overcoming doubts.

Don’t talk yourself into it, question yourself. And write down your answers. If you abandon the project, you will know why. If you decide to go on with it, your written answers will help you later, in times of difficulty and stress.

Why did you like the script or the novel or the idea when it was first presented? What was it that attracted you? What was it about the theme that touched your innermost being? If it didn’t stir you deeply, beware, because if you lack that kind of deep involvement, you may find halfway through that you have lost interest. You have become indifferent. The pleasure is gone.

Then get in trouble. Attack the project. That is often the best way to find out why you truly like it. Doubt yourself. Answer your worst questions. Don’t be afraid.

There is only one person you must give a bad time to, yourself. It is said that if a man has talent, it is only because he tells himself, from time to time, the truth he’s been trying to hide from himself. Do you truly like the project, or are you considering it for some curious, irrelevant reason? Be certain that your interest isn’t based primarily on showing off your facility: “I can make that work. I know how to solve these problems.” You are not building a house or doing summer stock. It’s part of your life, not show business.

This is when you must examine your own character, when you must force yourself to confront whether what you’re considering expresses your deepest wishes, your hopes, your longing, your anger. Does it speak for you? Does it touch some fundamental strain in you? Tell yourself the truth; don’t be an agreeable good guy. Be selfish. Be arrogant. Can it be made part of the current of your own life? You’re paying a big price to involve yourself—months, even years of your life. Can the finished project be thought of as a chapter in your autobiography? Can you make it speak for you? Will it stand as an expression of your own existence? Truly? In what way? Will you be proud that you’ve done it? You can be 100 percent only rarely, but you should feel the enthusiasm necessary to try to give the work your whole being. Is the theme in some way your theme? Is the story your story?

If you can’t find the you in the story, then it has no personal meaning for you. That’s an important discovery, because then you should immediately walk away from it. Don’t be lured into sticking with it by inertia or the sad faces of disappointed friends. They’ll find someone else.

Suppose your questioning comes out positive, and you believe your first enthusiasm was well-founded. Your notes on this project that you are fool enough to start will rekindle, reenlist, and reenlighten you when you later ask yourself what did you ever see in it. I’ve known them to be lifesavers, dispelling weariness and the crippling effect of doubt. And you will remember the pleasure you once felt. 1

Crafting Emotion

What a theatre or film director is essentially doing is conveying an emotion he has, arousing an emotion he feels in a group of other people. You must from the beginning recognize what audience you are addressing and how you propose to move them. What precisely you want to make them feel. Once this is done, take care not to tell them plainly what they should believe about what they’re being shown. Leave an element of doubt and mystery. Wonder is better than information.

Don’t patronize them. Don’t be a whore for them. Don’t tell them what they should think. But don’t play up to them. Let them come to their own conclusions. But know yourself what you’re reaching for in their feelings. This means isolating the theme. What it’s all about. What it should say in the end. But “say” is a dangerous word. “Convey” is better. Put down the theme, the meaning of the piece for you, in so many words. The size of a film or play depends on the size of its theme. One can have all kinds of conflicts, but if the central thematic issue is a small one, or petty, the clashes will be of no significance. 1

Practical Experience

As for the various functions of the craft you are involved with, the best way is to practice them yourself. It’s less important to read about acting and to study the advice of great teachers than to act yourself. If you can, work in a summer theatre. Or get a part in a play or a movie and submit to the will of the director. Design a set for a production, create the costumes for another. Knuckle down and do it.

Lighting is critical—you are creating another world, not a real world—and experience in this is absolutely necessary. You must know what the choices are and what the problems are and what the techniques are and what the available materials are before you can successfully guide others. Learn by doing. Fail, but try everything you can. Take subsidiary positions. Be an assistant director, a call boy, be a stage manager. Everything is relevant. 1

Personal Voice and Artistic Integrity

I believe I still have lots to learn from the many filmmakers whose work I admire. At the same time I have nothing to learn. My work prejudices have the merit of being my very own. My brother and sister filmmakers have various gifts and I admire them, but the whole thing is to speak your own language, whatever it is and wherever you come from, to make your own choices and be ready to stand alone.

I believe that filmmaking is one of the great arts, potentially the greatest, and perhaps the ultimate one. It hasn’t yet reached its full potential for artistic and social importance. You who labor in the field will find, as you progress, an ever deeper joy in this work. I think of filmmaking as a joyful privilege.

Who could ask for anything more than to have the opportunity—and the wherewithal—to convey by film a meaningful personal sentiment? Not the kind of message expressed by words only, but to pass on an experience dear to the writer, with the force of a poem, a communication that combines every expressive art—photography, language, music, acting, movement—devised by man, coming out of your own feelings and seeking to reach not only the few people who are close to you but the whole world.

The films that I don’t like are those where I don’t feel any personality. It doesn’t bother me that all Ingmar Bergman’s movies are alike. They should be because he made them. If he’s behind the camera I want to feel him, as I do in his films. The same with Antonioni and Fellini. I want to feel their own individual

personalities; I don’t want to be more eclectic or have fewer mannerisms (which I don’t try to have). But I do think you can see that all my films are made by me; for better or worse, I do the best I can. I don’t think any of them are perfect or wonderful, and some of the failures I like as well as, if not better than, the successes. 1

Most screenplays are adaptations of novels, stage plays, stories, news items, history. But the most interesting scripts verge on autobiography. The writer speaks to you, through the screen, using all the means of this form that are special to it, the succession of images as well as words. The best screen work has this element, even if the story appears to be objectively observed. The story is molded by the writer’s beliefs and feelings. 1

Artistic Rebirth And Emotions

An aging director must recognize that it is very difficult to fight one’s way back to the vanished self; it’s painful. But one day, in the spring or fall, those unstable months, suppose he surprises himself and wants it all back, whatever it was he once had. Suppose he is eccentric enough to want to test himself again. Suppose he merely wants to prevent the death he feels coming on him. He wants the old fire back, burning where it was in his good days. It’s a question of a rebirth. What he’s lost, he now recognizes, is the very source of what artistic inspiration he once had and enjoyed.

He looks at his last films and finds them disappointing, lesser stuff, in fact, failures. They seem to lack some essential emotion he once had that supplied the fuel that drove him. What was it? Anger, desire, competition? “Why,” he asks himself, “do I no longer feel what I once felt?” He knows the answer. He no longer really believes in himself, is no longer certain that he has that final energy—or that he can bring it back. Perhaps it’s gone for good. Which only makes him want it more.

Is it a question of isolating what he once had, reawakening it, and so perhaps coming to believe again that he has something special to say? He’s not sure he has. But he wants to give it a try, wants to make one final fundamental effort.

He finds that he has only one source for this intimate energy: his own life. He must make a film, however disguised, about a problem that is alive and kicking for him, that occupies every moment of his existence. His own feelings, however negative or devalued, are the most genuine he has: his anger and self-disgust, his essential unrest, his doubt about his own worth. He must put himself in danger, on the mortal block, and there, sacrificing all vanity, pride, until the life blood runs, there find rebirth through pain.

Then to his surprise he finds that those feelings of disappointment, fear, infinite sadness, all those black emotions are the realest he’s felt for a long time. His negativism is more worthy of respect than his old ebullient optimism. It is in his despair that he is in touch with truer emotions—and the most universal. They will, once expressed, affect all men because the theme of decline and failure that I have attributed to an aging director applies to us all. And the yearning for a reawakening, a leap back, is also universal.

When one’s belief in his or her own life fails, it can only be revived by delving deep into the subject, fearlessly, mercilessly. “Who the hell am I after all? Am I truly a successful artist? Who will in the end respect and remember me?” The answers are not flattering, but the very questions arouse the only true emotion he’s felt for a long time.

Such crises—“I have not lived up to my hopes for myself. I am not what I should be. I am worthless. I don’t know who I am anymore”—take place in the lives of all sensitive souls. Self-doubt is the curse of an artist’s life. Also his blessing. Often it is the key to his talent and so to his reawakening. His pain is the real thing—it is not just drama—and he should hold on to that emotion. And give it full dramatic play. Within his own darkness is the only place where the essential energy he now lacks can be found. That painful and shameful thing, that discouraging echo he hears bouncing off the cavern walls of his soul, is the essential energy he needs.

He must put himself and his talent and his career in mortal danger, and he will live again only as he emerges from it.

The Fountain of Youth is in yourself. 1

Sunday Museletter (Free)

Ignite your creativity with hand-picked weekly recommendations in music, film, books, and art — sent straight to your inbox every Sunday.

Next up: Alexander Payne on His Advice To Aspiring Filmmakers

References

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.