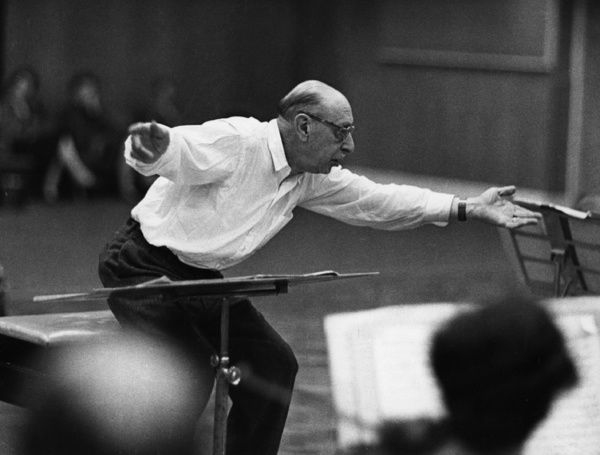

Igor Stravinsky on inspiration, advice for a young music composer, how melody is a gift, and why limitations enable freedom.

A brief overview of Igor Stravinsky before delving into his own words:

| Who (Identity) | Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky, a Russian-born composer, pianist, and conductor, renowned for his groundbreaking contributions to musical composition in the 20th century. |

| What (Contributions) | Stravinsky is famous for his diverse and innovative compositions, which spanned various musical styles including neoclassicism and serialism. Notable works include “The Rite of Spring,” “The Firebird,” “Petrushka,” and “Symphony of Psalms.” |

| When (Period of Influence) | Stravinsky’s career spanned the early 20th century, with his most influential period being from the 1910s to the 1950s. He played a key role in modernism in music. |

| Where (Geographic Focus) | Born in Oranienbaum, Russia, Stravinsky lived and worked in several countries, including Switzerland, France, and the United States, reflecting a global influence on his music. |

| Why (Artistic Philosophy) | Stravinsky’s work is characterized by its rhythmic energy, innovative orchestration, and ability to evoke a wide range of emotions and atmospheres. He sought to push musical boundaries and often drew inspiration from Russian folklore. |

| How (Technique and Style) | Known for his versatile and innovative approach, Stravinsky’s style evolved significantly over his career. His early works were marked by a vivid use of rhythm and orchestration, while his later works embraced a more structured and orderly form, influenced by classical music traditions. |

This post is a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with citations found at the end of the article.

Musical Creative Process

Long before ideas are born I begin work by relating intervals rhythmically. This exploration of possibilities is always conducted at the piano. Only after I have established my melodic or harmonic relationships do I pass to composition. Composition is a later expansion and organisation of material. 1

Daily Routine

“I get up at about eight, do physical exercises, then work without a break from nine till one,” Stravinsky told an interviewer in 1924. Generally, three hours of composition were the most he could manage in a day, although he would do less demanding tasks–writing letters, copying scores, practicing the piano–in the afternoon.

Unless he was touring, Stravinsky worked on his compositions daily, with or without inspiration, he said. He required solitude for the task, and always closed the windows of his studio before he began: “I have never been able to compose unless sure that no one could hear me.” If he felt blocked, the composer might execute a brief headstand, which, he said, “rests the head and clears the brain.” 2

Stravinsky worked at least ten hours a day for many years. Beginning by playing a Bach fugue on the piano, he would compose for four to five hours in the morning and then, after lunch, orchestrate and transcribe for the rest of the day.

His approach was very orderly; as his biographer Mikhail Druskin notes: “Stravinsky’s work table resembled that of a surgeon rather than that of a composer. The neatness and precision of his scores recalled those of a map, with every syllable, every note, and every rest perfectly drawn.”

He had available all conceivable writing implements and scoring paraphernalia he might need, and he used these like the most highly skilled craftsman. 3

Advice For A Young Composer

A composer is or isn’t; he cannot learn to acquire the gift that makes him one, and whether he has it or not, in either case, he will not need anything I can tell him. The composer will know that he is one if composition creates exact appetites in him and if in satisfying them he is aware of their exact limits.

Similarly, he will know he is not one if he has only a “desire to compose” or “wish to express himself in music.” These appetites determine weight and size. They are more than manifestations of personality, are in fact indispensable human measurements.

I would warn young composers too, Americans especially, against university teaching. However pleasant and profitable to teach counterpoint at a rich American Gymnasium like Smith or Vassar, I am not sure that that is the right background for a composer.

The numerous young people on university faculties who write music and who fail to develop into composers cannot blame their university careers, of course, and there is no pattern for the real composer, anyway.

The point is, however, that teaching is academic, which means that it may not be the right contrast for a composer’s non-composing time. The real composer thinks about his work the whole time; he is not always conscious of this but he is aware of it later, when he suddenly knows what he will do. 1

Inspiration

For me, as a creative musician, composition is a daily function that I feel compelled to discharge. I compose because I am made for that and cannot do otherwise. Just as any organ atrophies unless kept in a state of constant activity, so the faculty of composition becomes enfeebled and dulled unless kept up by effort and practice.

The uninitiated imagine that one must await inspiration in order to create. That is a mistake. I am far from saying that there is no such thing as inspiration; quite the opposite. It is found as a driving force in every kind of human activity, and is in no wise peculiar to artists. But that force is only brought into action by an effort, and that effort is work.

Just as appetite comes by eating, so work brings inspiration, if inspiration is not discernible at the beginning. But it is not simply inspiration that counts; it is the result of inspiration—that is, the composition. 4

Most music-lovers believe that what sets the composer’s creative imagination in motion is a certain emotive disturbance generally designated by the name of inspiration.

I have no thought of denying to inspiration the outstanding role that has devolved upon it in the generative process we are studying; I simply maintain that inspiration is in no way a prescribed condition of the creative act, but rather a manifestation that is chronologically secondary. 5

Limitations Enable Freedom

The creator’s function is to sift the elements he receives from her, for human activity must impose limits upon itself. The more art is controlled, limited, worked over, the more it is free.

As for myself, I experience a sort of terror when, at the moment of setting to work and finding myself before the infinitude of possibilities that present themselves, I have the feeling that everything is permissible to me.

If everything is permissible to me, the best and the worst; if nothing offers me any resistance, then any effort is inconceivable, and I cannot use anything as a basis, and consequently every undertaking becomes futile.

Will I then have to lose myself in this abyss of freedom? To what shall I cling in order to escape the dizziness that seizes me before the virtuality of this infinitude? However, I shall not succumb.

I shall overcome my terror and shall be reassured by the thought that I have the seven notes of the scale and its chromatic intervals at my disposal, that strong and weak accents are within my reach, and that in all of these I solid and concrete elements which offer me a possess field of experience just as vast as the upsetting and dizzy infinitude that had just frightened me. It is into this field that I shall sink my roots, fully convinced that combinations which have at their disposal twelve sounds in each octave and all possible rhythmic varieties promise me riches that all the activity of human will never exhaust.

What delivers me from the anguish into which an unrestricted freedom plunges me is the fact that I am always able to turn immediately to the concrete things that are here in question. I have no use for a theoretic freedom. Let me have something finite, definite matter that can lend itself to my operation only insofar as it is commensurate with my possibilities. And such matter presents itself to me together with its limitations. I must in turn impose mine upon it.

My freedom thus consists in my moving about within the narrow frame that I have assigned myself for each one of my undertakings.

I shall go even further: my freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles. Whatever diminishes constraint, diminishes strength. The more constraints one imposes, shackle the more one frees one’s self of the chains that shackle the spirit. 5

Sponsored: Canvas wall art paintings of nature and the cosmos.

Expanding On A Musical Idea

You should not suppose that once the musical idea is in your mind you will see more or less distinctly the form your composition may evolve. Nor will the sound (timbre) always be present.

But if the musical idea is merely a group of notes, a motive coming suddenly to your mind, it very often comes together with its sound.

When my main theme has been decided I know on general lines what kind of musical material it will require. I start to look for this material, sometimes playing old masters (to put myself in motion), sometimes starting directly to improvise rhythmic units on a provisional row of notes (which can become a final row). I thus form my building material. 1

Getting & Remembering Ideas

Ideas usually occur to me while I am composing, and only very rarely do they present themselves when I am away from my work. I am always disturbed if they come to my ear when my pencil is missing and I am obliged to keep them in my memory by repeating to myself their intervals and rhythm.

It is very important to me to remember the pitch of the music at its first appearance: if I transpose it for some reason I am in danger of losing the freshness of first contact and I will have difficulty in recapturing its attractiveness. Music has sometimes appeared to me in dreams, but only on one occasion have I been able to write it down. 1

The Audience Reaction To His Compositions

When I compose something, I cannot conceive that it should fail to be recognised for what it is, and understood. I use the language of music, and my statement in my grammar will be clear to the musician who has followed music up to where my contemporaries and I have brought it. 1

Composing & Mathematical Thinking

It is [music], at any rate, far closer to mathematics than to literature — not perhaps to mathematics itself, but certainly to something like mathematical thinking and mathematical relationships. (How misleading are all literary descriptions of musical form!) I am not saying that composers think in equations or charts of numbers, nor are those things more able to symbolize music.

But the way composers think — the way I think –is, it seems to me, not very different from mathematical thinking. I was aware of the similarity of these two modes while I was still a student; and, incidentally, mathematics was the subject that most interested me in school.

Musical form is mathematical because it is ideal, and form is always ideal, whether it is, as Ortega y Gasset wrote, “an image of memory or a construction of ours.” But though it may be mathematical, the composer must not seek mathematical formulae. 1

Music vs Painting

The plastic arts are presented to us in space: we receive an over-all impression before we discover details little by little and at our leisure. But music is based on temporal succession and requires alertness of memory. Consequently music is a chronologic art, as painting is a spatial art. Music presupposes before all else a certain organisation in time. 5

Piano Lessons

I learned to play the Mendelssohn G-Minor Concerto with Mile. Kashperova [his piano teacher], and many sonatas by Clementi and Mozart, as well as sonatas and other pieces by Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, and Schumann. Chopin was forbidden, and she tried to discourage my interest in Wagner. Nevertheless, I knew all Wagner’s works from the piano scores, and when I was sixteen or seventeen, and at last had the money to buy them, from the orchestral scores.

I am most in Kashperova’s debt, however, for something she would not have appreciated. Her narrowness and her formulae greatly encouraged the supply of bitterness that accumulated in my soul, until, in my mid twenties, I broke loose and revolted from her and from every stultification in my studies, my schools, and my family. The real answer to your questions about my childhood is that it was a period of waiting for the moment when I could send everyone and everything connected with it to hell. 6

What He Read In His University Years

Russian literature mostly, and the literature of other countries in Russian translation. Dostoievsky was always my hero. Of the new writers, I liked Gorky most and disliked most Andreyev. The Scandinavians then so popular —Lagerlof and Hamsun—did not appeal to me at all, but I admired Strindberg and, of course, Ibsen.

Ibsen’s plays were as popular in Russia in those years as Tchaikovsky’s music. Sudermann and Hauptmann were also in great vogue then, and Dickens, and Mark Twain (whose daughter I later knew in Hollywood), and Scott, whose Ivanhoe (pronounced in Russian as a four-syllable paroxytone—Ivanhoye ) was as popular a children’s book as it ever was in the English-speaking countries.

An Artist Must Avoid Symmetry

Mondrian’s Blue Façade (composition 9, 1914) is a an example of what I mean [image below]. It is composed of elements that tend to symmetry but in fact avoids symmetry in subtle parallelisms. Whether or not the suggestion of symmetry is avoidable in the art of architecture, whether it is natural to architecture, I do not know.

However, painters who paint architectural subject matter and borrow architectural designs are often guilty of it. And only the master musicians have managed to avoid it in periods whose architecture has embodied aesthetic idealisms, i.e., when architecture was symmetry and symmetry was confused with form itself.

Of all the musicians of his age Haydn was the most aware, I think, that to be perfectly symmetrical is to be perfectly dead. We are some of us still divided by an illusory compulsion towards “classical” symmetry on the one hand, and by the desire to compose as purely non-symmetrically as the Incas, on the other. 1

What Is Technique?

The whole man. We learn how to use it but we cannot acquire it in the first place; or perhaps I should say that we are born with the ability to acquire it. At present it has come to mean the opposite of “heart,” though, of course, “heart” is technique too. A single blot on a paper by my friend Eugene Berman I instantly recognise as a Berman blot.

What have I recognised — a style or a technique? Are they the same signature of the whole man? Stendhal (in The Roman Promenades) believed that style is “the manner that each one has of saying the same thing.” But, obviously, no one says the same thing because the saying is also the thing. A technique or a style for saying something original does not exist a priori (A priori is a term applied to knowledge considered to be true without being based on previous experience or observation), it is created by the original saying itself.

We sometimes say of a composer that he lacks technique. We say of Schumann, for example, that he did not have enough orchestral technique. But we do not believe that more technique would change the composer. “Thought” is not one thing and “technique” another, namely, the ability to transfer, “express,” or develop thoughts.

We cannot say “the technique of Bach” (I never say it), yet in every sense he had more of it than anyone; our extraneous meaning becomes ridiculous when we try to imagine the separation of Bach’s musical substance and the making of it.

Technique is not a teachable science, neither is learning, nor scholarship, nor even the knowledge of how to do something. It is creation and, being creation, it is new every time. 1

His Favourite Music

I play the English virginalists with never-failing delight. I also play Couperin, Bach cantatas too numerous to distinguish, Italian madrigals even more numerous, Schütz sinfoniae sacrae pieces, and masses by Josquin, Ockeghem, Obrecht, and others.

Haydn quartets and symphonies, Beethoven quartets, sonatas, and especially symphonies like the Second, Fourth, and Eighth, are sometimes wholly fresh and delightful to me.

Of the music of this century I am still most attracted by two periods of Webern: the later instrumental works, and the songs he wrote after the first twelve opus numbers and before the Trio-music which escaped the danger of the too great preciosity of the earlier pieces and which is perhaps the richest Webern ever wrote. 1

Melody

Melody, Melddia in Greek, is the intonation of the melos, which signifies a fragment, a part of a phrase. It is these parts that strike the ear in such a way as to mark certain accentuations. Melody is thus the musical singing of a cadenced phrase. I use the word cadenced in its general sense, not in the special musical sense.

The capacity for melody is a gift. This means that it is not within our power to develop it by study. But at least we can regulate its evolution by perspicacious self-criticism.

The example of Beethoven would suffice to convince us that, of all the elements of music, melody is the most accessible to the ear and the least capable of acquisition. Here we have one of the greatest creators of music who spent his whole life imploring the aid of this gift which he lacked.

So that this admirable deaf man developed his extraordinary faculties in direct proportion to the resistance offered him by the one he lacked, just the way a blind man in his eternal night develops the sharpness of his auditive sense.

I am that melody must keep its place at the summit of the hierarchy of elements that make up music. Melody is the most essential of these elements, not because it is more immediately perceptible, but because it is the dominant voice of the symphony not only in the specific sense, but also figuratively speaking. 5

Sunday Museletter (Free)

Ignite your creativity with hand-picked weekly recommendations in music, film, books, and art — sent straight to your inbox every Sunday.

Next up: Kurt Vonnegut on the purpose of art.

References

- Conversations with Igor Stravinsky by Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft

- Daily Rituals by Mason Currey

- Creating Minds: An Anatomy of Creativity Seen Through the Lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Ghandi, Howard Gardner

- An Autobiography, Igor Stravinsky

- Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons by Igor Stravinsky

- Memories and Commentaries, Igor Stravinsky & Robert Craft

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.