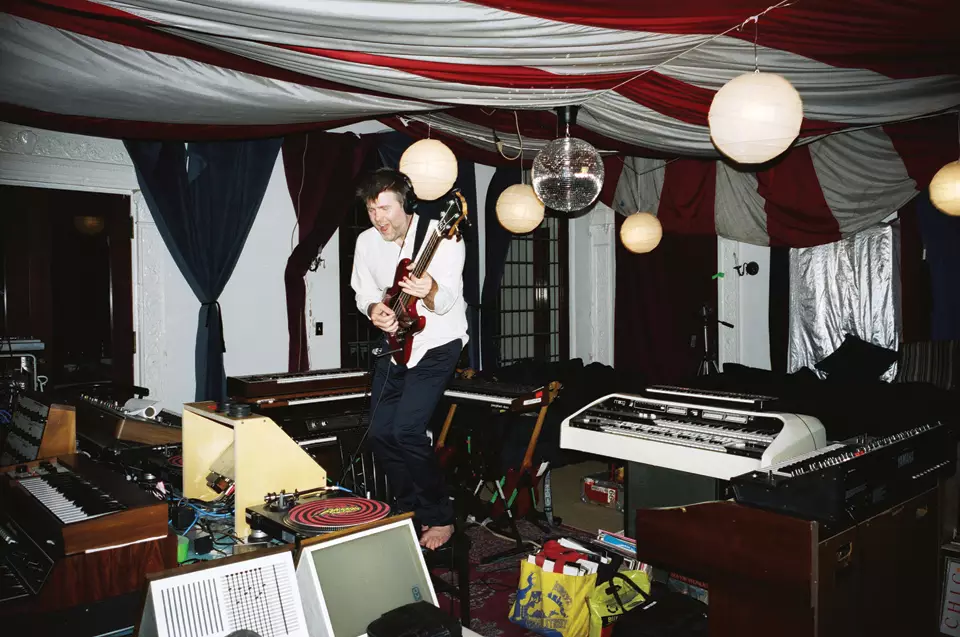

James Murphy on his creative process, musical influences, discovering dance music, and his favourite drum machine and synths.

James Murphy (b. 1970) is a LCD Soundsystem mastermind who turned Brooklyn dance-punk into middle-aged catharsis. With DFA Records, cowbells and sardonic lyrics (“Losing My Edge”), he bridged indie rock and club culture, paused in 2011, then roared back with 2017’s chart-topping American Dream.

This post is a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with citations found at the end of the article.

Good Idea vs. Talent

A good idea is more important than being naturally talented, I think it’s much more important. A good idea, an open mind, and hard work beat talent any day. Talent usually is just someone who is afraid to fail and stays at home. 1

His Journey From Failure To Success

I was really a failure. I dropped out of college to make music but then I stopped making music. I was not even an epic failure, but a sad pathetic failure. A real epic failure you could get behind, like “I tried this big thing and it failed and I lost everything”. No, I just frittered my years away doing nothing, being in dead-end relationships and dead-end bands. I didn’t take responsibility for much; I just felt bad for myself and wondered why my life wasn’t better.

When I was about 26, I realized that my life was not at all going the way I wanted it to go. This was not what I expected. I was always the youngest guy. When I was 16, I was in a band where everybody else was in their 20s. I was the songwriter and singer who played guitar, always the kid. Then suddenly at 26, I wasn’t doing anything and I thought that just seemed too old to be doing nothing.

Not long after, David Foster Wallace put out the book “Infinite Jest” and it floored me. It really depressed me because I thought if I started right now, he’s older than me but if I started right now, I wouldn’t get it done in time to be done with something like that by the time I was his age and have it come out. It’s not possible. So I was pretty disappointed with myself. I went to therapy with an amazing person and admitted, “I’m not good at my life. I’m just bad at it. I don’t care what it is. I just want to not do this anymore. I need to do something else.”

I started realizing I was lazy, but lazy never felt right when I heard that. It wasn’t that I was lazy; I was just really afraid. I was really afraid of failing. All my life I’d been precocious. I was supposed to be smart and creative. Hearing those things makes you scared that you’re going to do something stupid or uninteresting and no one will see you as smart or creative anymore.

I’ve never been given credit for being hardworking or diligent. All my credits were based on attributes I had no control over, like being tall. I realized that I had been so afraid of failing and looking bad that I didn’t do anything. I did nothing. I could claim some sort of safety in doing nothing, but then I decided that’s pathetic. I need to work against all of my instincts and start doing things.

That’s when I started a record company, built a studio, and became aggressive in engaging with culture, which was fun. I never really engaged with culture before. If there were cool people in New York City, I would be sour grapes about it. I’d be bitter, thinking, “I don’t want to go to that place. It’s lame. Those people think they’re so cool.”

I decided to go and see if 10 percent of those people were fun. Like every other group, 10 percent are pretty alright. Ninety percent of most groups are kind of terrible, but 10 percent are decent. So I started going to different types of things and meeting different people, started throwing parties and suddenly, I was kind of cool. I’d never been cool. I’d always been a total nobody, invisible, sad, and shy.

Then one night, I went to see a band and someone else was playing the records that I was playing. Nobody else was playing those records before; that was my thing. I got really mad and defensive, thinking, “That’s my thing. What the hell? Some 22-year-old kid?” I got really embarrassed because I didn’t write those records; I just owned them. You can’t be proud of yourself for owning them. But I was mad because I knew that kid was at one of my parties, and it was a dense conflict I couldn’t resolve.

That’s where “Losing My Edge” came from. I was angry, but also pathetic for being angry. It felt dense and easy to write from, easy to make something from.

I made that song and everybody thought it was terrible. I remember playing it for people and they would give me this face like they didn’t want to say anything. They’d ask technical things like, “What’s the one on the drums?” and I’d think, “Okay, you don’t like this.” Only Phil Mossman, the original LCD guitar player, liked it. He was older than me and found it really funny. So we put it out. My partners Tim and John thought I was making a big mistake and would look like an idiot. It was the B-side until the last minute, but I insisted it should be the A-side. I wanted to sink or swim with that.

It had a huge impact on the scene. I know how many we made and it’s not that many, about four or five thousand twelve inches. To me, that was huge, but it kind of became a song that everybody knew. I realized people got music from the internet. We only sold about four thousand copies, so clearly some of them didn’t go home with people.

I started meeting people, making friends with other musicians. It was kind of the story of their lives too. I met the Optimo guys from Glasgow early on, and they felt it was the story of their lives too, this sad period of time wondering what to do with yourself. I had a job for the first time. I had made music my whole life, but this was the first time I made music that wasn’t trying to be something else. I was just trying to be as much myself as possible for the first time and people liked it. That was remarkable and a big change for me.

I’ve become an intense proponent of my friends. I’m hardworking and effective, making good decisions and being reliable. People now see me as on top of things, but I was a disaster. I try to encourage my friends, saying, “Just make something. Don’t worry about it. Stop overthinking. Just make it and put it out.” They think it’s easy for me, but I tell them, “When I was your age, I was still five years from putting out ‘Losing My Edge’. I was five years from complete failure. You’re doing great. You’re actually doing fine.” 2

Creative Process

Whether I compose lyrics beforehand or just improvise – The short answer is that it depends on the song. The longer answer would be is that the most normal way it goes, is while I’m working on the music there’s some lyrics– maybe a hook– that are kind of bouncing around. And I’m unconsciously kind of singing that to myself while I’m working on a song. So like, things start to expand and get meaning and have an overall kind of intent or tone. Then when it comes time to sing, I’ll just set up a microphone and just go sing. Just do a take where I’ll just make it up– just automatic singing. And then I’ll listen to that and there’ll be things that I like. And probably what’s going to happen is I’m going to keep that take just so I have something to work with, then I’ll go back and fix things that I don’t like. Or re-do the whole thing or write it out, but usually it starts from a position of honesty.

With revision then, it depends on the song. Usually if I go back and rework them, they tend to get square in shape. Meaning I start getting obsessed with each verse being a certain number or syllables or something. But when I just go sing, they have very different shapes from verse to verse. Which I like better. I don’t think it’s something that you notice necessarily but if it wasn’t there, it would feel very different. 3

Discovering Dance Music

Dance music changed my life because I realized that making people dance had a point that had nothing to do with art. I mean that in the most positive way, meaning that it’s like food. If they’re not eating it, you’ve screwed it up. If they’re not dancing, you’re not doing a good job. It made a very simple set of goals for me, which allowed me to calm down and stop wondering if what I was doing was good or worthwhile. I could make people dance, make people have fun. That was a great weight off my back after years of self-mythologizing, thinking, “Am I good? Am I going to be like David Bowie? Can I ever be like all these people? I’m never going to be in Velvet Underground. What am I? Who am I?” This silenced that voice long enough for me to make some songs. 4

Persevering Through Limited Options

Limited options kept me hanging in there. I dropped out of college and was in a bad band. The only thing I knew how to do was run sound, build sound systems, and fix them. I was a live engineer for bands, making money by working for 80 bucks a night at places like Maxwell’s in Hoboken or Brownies on Avenue A. Sometimes, I’d go on tour with a band.

I was around music all the time. I had a studio in DUMBO, paying $375 a month for a space in a really fancy building on the Waterfront in Brooklyn. I was the only tenant and had a little studio where I could make music. Every penny I earned went into equipment. I was kind of stuck; I didn’t know what else I could do. That was it.

In ’93, I did a guy a favor. He moved to New York with a bunch of studio equipment and had no place to put it, so I let him store it in my studio. He could use my studio once in a while if he wanted to. I kind of forgot about it. Then, when I got kicked out of my studio so they could build luxury high-rises, I had to tell him to take his stuff back. He said he had just gotten a space, and I asked if I could store my stuff there temporarily. We ended up combining our equipment, and I told him if he knew a space where I could build a new studio, to let me know. He said, “Totally.” He asked if I knew someone who could design a studio because he wanted to build one. I said, “I can do that here,” and that became DFA Studios.

Tyler Brody is one of those people without whom my whole situation wouldn’t exist. He helped build the label and the studio, giving me a place to work. 4

Music Discovery, Technology, And Taste Engines

I love the internet for finding things, but it’s not quite the same as like just finding a record that has a cool cover and that being what draws you to it. And you buy it and it’s horrible, and the next one you do that to is amazing. What’s going to be missing is like the unconscious peer pressure that guides people into different forms of taste. What’s going to be replaced by is lifestyle marketing and taste engines, which scares the crap out of me. As much as I hate like proto-fascist punk rock peer pressure, I fear lifestyle marketing and taste, you know, demographic generation engines. That kind of freaks me out.

Will they ever have the kind of specific influence that record clerks and local DJs did? I don’t see where that comes from. Like, I get it. People can be led to different music through these kind of taste engines. But the taste engine isn’t a qualitative judgment. It’s sort of a theme judgment. And some of the best records I found weren’t because some dude’s like, “Dude, you like Dinosaur Jr.? You love Sade.” It was more like just a guy behind a counter that’s playing Terry Riley in the background and you not having ever heard anything as crazy as that and needing to buy it even though you mostly listen to new Romantics. 5

Journey From Ego To Perspective

I started out as a singing guitar player, which is another way of saying I was a terrible egomaniac jerk as a youth. Then I stopped. I became a drumming engineer, which was a sort of self-imposed penance for making terrible music in my childhood. I thought, “I’m awesome. Things are going to work out so great for me. I don’t need to go to college or really take anything seriously. It’s just a matter of time.” Then I realized it really is a matter of time in a totally different way. My first life as a singing guitar player ended in tears and began my 22-year-old life as a drumming engineer, which ended in quitting. This led to my early 30s life, realizing, “Okay, get your head out of your ass. You don’t have a college degree and you don’t really have a good job because you make music, yet you’re not making music.”

Finding success later in life is one of the best things that ever happened to me for sure, because I don’t think I would have been a very happy person if I had been successful when I was young. I know a lot of people who were successful when they were young and some of them are happy and some of them are really, really not happy. I think it’s hard. I think life is really hard. I think happiness is really hard. Satisfaction is really hard. And if you get all the things that you’re supposed to look forward to and that make you feel great really early, you might not work out a lot of other stuff. You might not work out some things that are a little more, you know, maybe a little more fundamental than having people like you.

That’s why you meet crazy musicians. Musicians aren’t crazy because crazy people make music. Musicians are often crazy because making music makes you crazy, and being very successful at it can make you totally crazy. I’ve met so many people with faraway eyes, still carrying on a grudge from some other time. “Yeah, I remember in ’96 in that other band, Pearl Jam said we sucked, so fuck those guys.” I’m like, “Didn’t you just buy an island? Relax.” It makes people crazy because you don’t suddenly become happy. So you start finding problems when there really aren’t any.

Whereas if you learn that you’re not happy and that’s part of being human, you can appreciate it when good things happen and enjoy them. I’ve been lucky enough to have worked out a bunch of that stuff before getting the great niceness of having people like what I do. Now, I can enjoy it and have some perspective on it. It’s not something I deserve or something like, “Where’s the guy that’s supposed to tell me I’m awesome and give me a bunch of money? Where’s that guy?” If somebody had done that when I was a kid, and then when I was 24, they weren’t doing it anymore, I would have been so angry. I would have been the worst guy. Maybe not. 4

Discovering The Power Of Hypnotic Music

For about an hour, I was a very trancy kid. I was a really psychedelic little kid. I was very into the physicality of music, and “Tomorrow Never Knows” was always my favorite Beatles song because it wasn’t cerebral. It wasn’t like, “And here’s another clever chord change.” It was just this relentless, hypnotizing thing. I was always entranced with things that were really hypnotizing. I used to listen to humming machines, anything repetitive and loopy, like Chopin’s barcarolles, lullabies, things that were monotonous. When I found the band Can, I was in heaven because it was like, here’s this for 30 minutes. 4

Favourite Drum Machine

My favourite drum machine is probably the 808 or the 606 for different reasons. And the Wurlitzer Sideman has this incredibly deep kick drum that I use a sample of all the time when you need something underneath that doesn’t take up any space. It just makes you feel like the bottom dropped out. It’s like adding subwoofers to something. And I really like that. Rather than making too big of a kick drum, I can just slide the Sideman underneath. 4

The Moment That Changed My Musical Life

There are a lot of moments, to be honest. Dating back earlier, there are people and moments that have made an impact. I was working with a guy who was making music, taking all these chances, and it wasn’t very good. I was complaining about it a lot, thinking, “He’s doing all this stuff, he thinks he’s so great.” Then I realized, what was I doing? I thought, “Okay, I’m that guy. I don’t like this guy. If I make a movie and the character doesn’t make music, sits around listening to records, and complains about other people, I don’t like that guy. That guy sucks.”

That moment made me realize, maybe I should just make things instead of complaining. I didn’t effectively shut up, but I did start making things, which was better. There are many moments, a lot of nights out where my life changed, a lot of waking up in the middle of the night. One seemingly insignificant revelation came after making the first LCD Soundsystem record. I woke up three months before making the second record and thought, “I have to make the next record so much better.” When I said it, I realized it didn’t mean much, but to me, it meant a lot. I figured out that I could try and make things better rather than settling on an idea.

Reading the book “Outliers” by Malcom Gladwell woke me up to how many different people and very lucky circumstances changed my life into making music. Before, you might believe in self-hype that you worked really hard and made this for yourself, but I am very aware that’s not the whole truth. It’s more about other people than specific moments. 4

Early Musical Influences

Early on, I really loved the Beatles. When I was really little– six or seven. But I have older brothers and sisters. So I was picking from a menu that was already there. I’m the youngest by a lot. My brother was into, like, Todd Rundgren, Utopia, Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, and Yes. He had a couple other records that I was more into than he was. He had David Live— the David Bowie live record– which I always found really terrifying. My other sister had some pop-rock records like Kansas; there was some Blue Oyster Cult floating around.

Across the street, my best friend had a bunch of older brothers who all had pretty different taste. Like, one brother was into new wave really early– like, the Knack. The other brother was into metal– pretty heavy sludgy shit. And the third brother was really into the Stooges, the Dead Boys, the Dolls, Velvet Underground. So I had a pretty amazing wide range of music. A range of what it was like to be a kid in the 70s.

But some of the first songs that I was really attached to were… I really liked Harry Belafonte when I was really little. Like “Day-O”. All the early Harry Belafonte stuff just sounds awesome. And “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.” Things like that, really floaty music. Then “Love Is Like Oxygen” by Sweet was my favorite song for a while. I don’t know why. I liked Cat Stevens when I was little. I liked Yes a lot. For my birthday when I was eight I got a record player and two Yes albums. But before that, when I was seven, my first two records I bought were seven inches of “Fame” by David Bowie and “Alone Again Naturally” by Gilbert O’ Sullivan.

I was mostly spending my time being into Yes. I was pretty dedicated. Like, “I’m into Yes.” But I was just always really into music. Really into sounds. Trying to make my stereo louder somehow. I consider getting into what I would call “my” music around Talking Heads’ 77, Violent Femmes’ Violent Femmes, the first Clash record. The B-52s, the Police– I really liked the Police. Ghost in the Machine was a pretty big record so I was liking them up through that, Synchronicity was like too pop in a weird way. Clark Kent, OMD, the first Ministry records– the very first Ministry new wave stuff. New Order, Joy Division, this was around eighth grade. The first Sisters of Mercy twelves I really, really liked. 3

Favourite Synths

I go through phases in some ways, but there are a few that have been long standing essentials for me. First has to be the EMS Synthi A.

I got one of these back in ’98 on the recommendation of either Tim Goldsworthy or Jagz Kooner to use on a David Holmes record. It was a baffling machine at first. Tim showed me the basics, which kind of exploded my mind (thanks, Tim) and since then I’ve just gone deeper and deeper with it. I love the output filters, which people seem to ignore. They’re just a fixed Q hi/lo tilt, but they’re critical to the sound, in my opinion. The interface is really intuitive and has pretty limitless potential routings, which makes this thing much more powerful than almost any other hardware synth. And its capacity for musicality and melody are often overlooked. After years of using it for sound treatments and crazy effects, I started using it for core musical elements and melodies, which was a revelation. The swooping chords in the LCD song “Someone Great” are the EMS.

I programmed the corners of the ranges for the joystick to control osc1 (x axis pitch) and osc2 (y axis pitch) to make up the various chords, while using the volume out of osc3 manually to blend in a fixed, lower note. The ability to flux the notes into freeform chaos during the transitions and then snap them into the next chord was really only possible with the joystick.

I’ve also used it to filter just about everything I could run through it. It still goes with me whenever I’m asked to show up and “produce” someone, etc. It’s a magical beast with beautiful possibilities, and I’m glad I spent the time to understand it over the past 20 years. A few years ago I was working on a funny track with Dave and Steph Dewaele, and we talked about making some animal noises for it, a la Cerrone’s “Supernature”, and I was quickly able to make monkeys, birds, roaring big cats, etc. It’s just such a versatile thing, which is fun to be “adept” with. Makes me feel like a weird old watchmaker.

For sheer beauty and the ability to pull on my heart I’m going to also say the Roland Jupiter 4. Nothing sounds as soft and lush. It has a very distinct color, but can do a pretty wide variety of things, but each of those things have this lovely, gentle harmoniousness, which can only come from the 4. I’ve recently had one of mine MIDI’d up, but I’m desperate to get this other specific MIDI mod which is eluding me. Apparently someone came up with a way to control every parameter in greater detail (as well as generate a far greater number of user memory presets) with an i/o, but that hardware has been harder to come by. I’ve been looking for years. There’s not much to say about it other than it sounds better to my ears to almost any other synth.

There are a few weird machines that I love, which I’m looking for, also. I used a Powertran Polysynth on the last LCD LP. It’s a funny 4 osc synth with a simple interface which is different from most synths. More independent control of the oscillators. Really unstable and wonderful. Instant Chris and Cosey sounds. And a Maplin matrixsynth, which is a big dumb box with a Synthi style patchbay. Used that also, but I don’t own it, which makes me jealous.

I guess, lastly, I use the shit out of my Roland System 100M, mixed with a few SH-101s. It’s a bassline killer. Wait—there’s more. I’m being stupid here. The Yamaha CS-60 has been the staple of early DFA mixes since the beginning.

Rayna Russom modded ours to take audio in the back and turn it into useable voltages, which is pretty useful. And the Oberheim OB-8… there’s a lot of synths I really love, frankly.

The outlier is the Korg microKORG. We use that live for almost everything, and I can program that idiot box like nobody’s business. Honestly, I can get nearly any sound out of it that I need. I make sounds on the grip of powerful vintage synths in the studio, then copy them—remarkably effectively—on the Korg for live. It’s an amazing machine. I’ve NEVER “generated” a sound on it. I don’t like it for that at all. But as a clinical tool for copying live sounds, there’s never been anything like it. I just wish there was a 16 voice version. 6

A short note

Each Sunday, I share a free email called The Creative Capsule featuring two carefully chosen works: one album and one film.

It’s short, ad-free, and designed to help you decide what to watch or listen to without scrolling.

Next up: Scott Adams on How To Become Successful.

- Electric Picnic – 2010 LCD Soundsystem, RTE2fm, YouTube

- Interview with James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem about how to deal with Failure, YouTube

- LCD Soundsystem Interview, Joe Colly, Pitchfork

- James Murphy talks LCD Soundsystem and Disco Drums | Red Bull Music Academy, Red Bull Music Academy, YouTube

- James Murphy, LCD Soundsystem, m ss ng Interview 2006, YouTube

- Interview with James Murphy, Synth History

Notes & Sources

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week. Download your free creative reset guide

Download your free creative reset guide