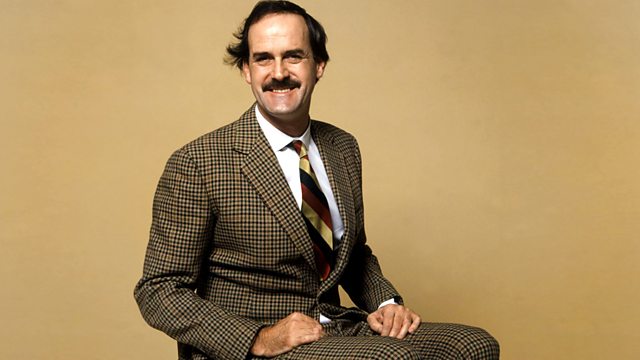

John Cleese on his rules for comedy, advice for writers, creativity, and why a good sense of humour is the sign of a healthy perspective.

A brief overview of John Cleese before delving into his own words:

| Who (Identity) | John Marwood Cleese, a British actor, comedian, writer, and producer, best known for his work on the Monty Python comedy series and the sitcom “Fawlty Towers.” |

| What (Contributions) | Cleese is renowned for his innovative and influential work in comedy. He was a co-founder of the Monty Python comedy troupe, contributing to the TV series “Monty Python’s Flying Circus” and films like “Monty Python and the Holy Grail.” Cleese also co-created and starred in “Fawlty Towers,” one of the most acclaimed British sitcoms. |

| When (Period of Influence) | Cleese’s career began in the 1960s, and he became a prominent figure in British comedy, particularly through the 1970s and 1980s. His influence on comedy, with his unique brand of humor, extends to contemporary comedy writers and performers. |

| Where (Geographic Focus) | Born in Weston-super-Mare, England, Cleese’s career mainly took place in the United Kingdom, though he gained international recognition and influence. |

| Why (Artistic Philosophy) | Cleese’s comedy style is characterized by its surreal, satirical, and often absurd humor. He has a penchant for exploring the boundaries of comedy, often incorporating intellectual and literary references into his work. |

| How (Technique and Style) | Known for his tall stature and flexible physicality, Cleese’s comedic technique involves exaggerated mannerisms, precise timing, and a distinctively deadpan delivery. He often plays uptight, eccentric characters, using his physical and verbal comedy skills to create memorable and iconic comedic moments. |

This post is a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with citations found at the end of the article.

Advice For Writers

So if I may give a word of advice to any young writer who, despite the odds, wants to take a shot at being funny, it is this: Steal. Steal an idea that you know is good, and try to reproduce it in a setting that you know and understand.

It will become sufficiently different from the original because you are writing it, and by basing it on something good, you will be learning some of the rules of good writing as you go along. Great artists may merely be “influenced by” other artists, but comics “steal” and then conceal their loot. 1

Rules For Comedy

Falling over is always entertaining.

The shorter the funnier. I began to experience that whenever you could cut a speech, a sentence, a phrase or even a couple of words, it makes a greater difference than you would ever expect.

Always put the key funny word in a sentence at the end of it, as this will give it maximum impact; any words that follow it will soften its effect, causing the audience momentarily to hold back their laughter so that they do not miss what is still to be said.

Jokes are about stupidity, greed, envy, malise, lust, vengefulness, anger, obsession, humiliation.

The best advice I was ever given came from David Attenborough in the early seventies: he said, “Use shock sparingly.” So I now permit myself a “fucking” here and there: maybe four in a two-hour show. 1

The Greatest Killer of Creativity

The greatest killer of creativity is interruption. It pulls your mind away from what you want to be thinking about. Research has shown that, after an interruption, it can take eight minutes for you to return to your previous state of consciousness, and up to twenty minutes to get back into a state of deep focus.

But perhaps the biggest interruption coming from your inside is caused by your worrying about making a mistake. This can paralyse you. ‘Oh,’ you say to yourself, ‘I mustn’t think that because it might be WRONG.’ Let me reassure you. When you’re being creative there is no such thing as a mistake.

You can’t possibly know if you are going down a wrong avenue until you’ve gone down it. So, if you have an idea, you must follow your line of thought to the end to see whether it’s likely to be useful or not. You must explore, without necessarily knowing where you’re going. 2

Sponsored: Canvas wall art paintings of nature and the cosmos.

Favourite Books

What is your favourite book?

Confessions Of A Philosopher, by Bryan Magee. 3

Clarissa: John, are you reading anything at the moment? Have you got anything on your bedside table?

John: Yes, I’ve got two or three, because I tend to do that. I’m just reading Seize the Day by Saul Bello. I haven’t read that for a long time.I’ve just bought a book by Anatole France called The Gods Will Have Blood. He won the Nobel Prize.

Let me think what else I’m reading. There’s one I’ve just finished called The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes.

I just read a book very recently by woman called Susan Cain, about introversion (Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking). And that gave me, since I’m basically introverted, the confidence to understand my cast of mind a little better than I have before.

I read a book 34 years ago by Eysenck (The Biological Basis of Personality) and that was all extroversion-introversion too. I think that it told me an enormous amount about how my mind worked; so that was very helpful. And in more recent years, I’ve read The Black Swan, and I was quite shocked to realize how bad we all are at forecasting the future. And then I recently read a book called The Drunkard’s Walk.

I was going to suggest that Memories, Dreams and Reflections was a book that changed me but I’m not sure how. I think it was about rearranging my priorities. 4

The Master and His Emissary by Iain McGilchrist

This is probably the most interesting, most important book I’ve ever read. McGilchrist is a quite extraordinary man. He taught English at Oxford but decided he didn’t like the way people talked about poetry. So he became a psychiatrist, and worked on the neuro-imaging of the brain. His book is about the brain’s distinct hemispheres. He believes that they have different ways of living, of being in life, and that, in our present civilization, they’ve fallen out of balance.

Popper by Bryan Magee

To me, Karl Popper is the best philosopher of science of the last century. This little book taught me more about the philosophy of science than any other.

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

It’s been many years since I read this one, but I can still remember certain sequences: men riding horseback into battle, and the way they try to distract themselves from the fact that they could be dead or wounded terribly in an hour’s time.

The Bonfire of the Vanities by Tom Wolfe

Wolfe’s big novel about 1980s New York City is an absolutely superb book. It delighted me, and told me so much about a certain part of American society.

Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky by Maurice Nicoll

Nicoll, a British psychiatrist, was a pupil of Armenian philosopher and mystic George Gurdjieff. His multi-volume book contains, I think, the best advice on understanding one’s own psychology as looked at through the Esoteric Christian tradition.

Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis

I met Amis once and liked him very much. He was rather sour, but he wrote beautifully, and he did really manage to describe certain personalities. His first novel is about a fellow called Dixon, a history lecturer at a minor university. Dixon has wonderfully funny fantasies, and Margaret, his sometime girlfriend, is one of the most awful human beings in fiction. I remember reading this by the side of a swimming pool in Spain, and I was really quite bothering the people around me because I kept bursting into hysterical laughter. 5

Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-Term Fulfilment by George Leonard

Howard Gardner’s Frames of Mind.

Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence.

Laughter by Henri Bergson

J. B. Priestley’s Man and Time.

My friend William Goldman, whom I regard as one of the greatest of all screenwriters (and author of the best book about Hollywood, Adventures in the Screen Trade). 1

Why Artists Are Sometimes More Original When Younger

The Buddhists have a phrase for this — ‘Beginner’s Mind’ — expressing how experience can be more vivid when it’s not dulled by familiarity. It’s the psychological equivalent of the Law of Diminishing Returns.

This is why even the very best minds seem to produce work that can divide itself into three stages.

First, they produce original work as they learn their craft; second, when they’ve mastered their craft, they begin to express their mature ideas in their best works; third, there’s a tailing-off of their powers, as their insights become more familiar. 2

Recreating From Memory & The Unconscious

I learned that Peter Cook and Dudley Moore had just done a couple of wonderfully funny series called Not Only … But Also and I listened to their records over and over again, even setting myself exercises in which I tried to write their sketches out from memory, carefully checked what I had written against the recordings, and then tried to recall them again from scratch. I like to think I learned a lot about sketch construction from those two. 1

I sometimes collaborated with my friend Graham Chapman, and we had written a parody of a Church of England sermon. Graham and I thought it was rather a good sketch. It was therefore terribly embarrassing when I found I’d lost it. I knew Graham was going to be cross, so when I’d given up looking for it, I sat down and rewrote the whole thing from memory. It actually turned out to be easier than I’d expected.

I discovered that the remembered version was actually an improvement on the one that Graham and I had written. I was forced to the conclusion that my mind must have continued to think about the sketch after Graham and I had finished it. And that my mind had been improving what we’d written, without my making any conscious attempt to do so. So when I remembered it, it was already better.

So I began to realise that my unconscious was working on stuff all the time, without my being consciously aware of it. 2

How Creativity Develops

Research has shown that constant relocation in childhood is often associated with creativity. It seems that the creative impulse is sparked by the need to reconcile contrasting views of the world. If you move home, you start living a slightly different life, so you compare it with your previous life, note the divergences and the similarities, see what you like better and what you miss, and as you do so, your mind becomes more flexible and capable of combining thoughts and ideas in new and fresh ways.

There’s also another way creativity can develop: if important people in your life, especially parents, have different ways of viewing the world, you find yourself trying to understand what they have in common, and how they contrast, in an attempt to make sense of their conflicting views. 1

Two Sides Of The Brain

‘Your logical, thinking side balances your creative side. Almost everyone has one side stronger than the other.’ This caught my curiosity, and over the years I came to the conclusion he was right, because the people who were more creative than me didn’t seem very strong at analysis or construction, especially when it came to plot and to the careful building of emotion within a scene; whereas the ones who analysed well were good at verbal wit and parody, but seemed very constrained creatively, unable to make the non-logical jumps (or even hops) over to where the richest comedy lay. Perhaps this explains why some witty people aren’t very funny, and why some very funny people can’t think straight. 2

What To Do When You First Get An Idea

It is very important that when you first have a new idea, you don’t get critical too soon. New and ‘woolly’ ideas shouldn’t be attacked by your logical brain until they’ve had time to grow, to become clearer and sturdier. New ideas are rather like small creatures. They’re easily strangled.

There’s quite a good way of telling when your creative period has done its job and it’s time to move on. If you find that you’ve had lots of vague new ideas and are starting to feel a bit overwhelmed and confused, that’s the moment to start work on clarifying them, prior to bringing your logical thinking to bear. Now you’re in a logical, critical period.

After a time there, however, when you’ve assessed everything, you will get a bit bored. That’s a sign that now is the moment to go back into your creative thinking mode again. And so you go backwards and forwards between the creative mode of thinking and the analytical mode of thinking until, finally, you get to something that’s a bit special. 2

Fear & Humour

What was so funny, I decided later, was not the anger itself, but the fear that underlay it. Basil’s {Fawlty from Fawlty Towers} anger is almost always underpinned by fear. Then, because of the stress caused by his fear he starts, at the beginning of each episode, by making small mistakes.

As his efforts to correct the fearful situation misfire, he becomes increasingly panicky and desperate and consequently his decision-making becomes worse and worse, until he has dug a hole, or several holes, for himself from which there is no real escape.

It’s just good, old-fashioned farce: (1) the protagonist has done something he has to cover up; (2) he makes increasingly poor choices due to his building panic; (3) he finishes up in ridiculous situations; (4) his sins are finally revealed (or he just escapes detection) and all’s well that ends well. 1

Creative vs Uncreative People

{In reference to a study of what separated creative architects from uncreative ones} The conclusion he came to was that there were only two differences between the creative and the uncreative architects.

The first was that the creative architects knew how to play. He describes this ability as ‘child-like’. Children at play are totally spontaneous. They are not trying to avoid making mistakes. They don’t observe rules. It would be stupid to say to them, ‘No, you’re not doing that right.’ At the same time, because their play has no purpose, they feel utterly free from anxiety (perhaps because adults are keeping an eye on the real world for them).

The second was that the creative architects always deferred making decisions for as long as they were allowed. They are able to tolerate that vague sense of discomfort that we all feel, when some important decision is left open, because they know that an answer will eventually present itself. 2

His Mothers Anxiety

And the reason for this was not that she was unintelligent, but that she lived her life in such a constant state of high anxiety, bordering on incipient panic, that she could focus only on the things that might directly affect her. It took me decades to realise that it was not the analysing of her worries that eased them; it was the continuous contact with another person that gradually calmed her. 1

Four Questions To Ask When Showing Someone Your Work

If you are an experienced writer, and you show people your work, there are four questions you need to ask:

1. Where were you bored?

2. Where could you not understand what was going on?

3. Where did you not find things credible?

4. Was there anything that you found emotionally confusing?

Once you have the answers to these, then you go away, decide how valid the problems are … and fix them yourself. 2

Learning to Say No

Because I wanted everyone to like me and to approve of me, I tried to be nice to everyone all the time and this proved a remarkably efficient way of losing control over my life. And all this agonising—this ridiculous time-wasting—was because it took me another thirty years to learn that if you say “No” in a friendly, chatty way, people accept it with great grace and goodwill, and do not hate you, or send death squads after you, or report you to the Daily Mail.

Nowadays I have a simple rule: you can ask me anything you like, provided I can say “No.” 1

How To Fake Self-Confidence

Self-confidence seemed to me more mimicry than anything else and I suggested visiting Clifton Zoo to watch the leaders in a group of baboons, and learn from them: make your gestures slow and deliberate; cultivate a deeper voice; appear casual at all times; eschew all rapid movements.

That was all you had to do to look confident. I also knew that I could “do” confident, and it helped enormously socially that I appeared to be able to fake it no matter how insecure, anxious, or inferior I actually felt. And I did feel insecure. It was the Bartlett effect: the sense that I should be formidably well informed about everything, when in reality I was quite ignorant. 1

Creativity & The Open Mode

We’ve become fascinated by the fact that we can usually describe the way in which people function at work in terms of two modes: open and closed.

By the “closed mode” I mean the mode that we are in most of the time when at work. We have inside us a feeling that there’s lots to be done and we have to get on with it if we’re going to get through it all. It’s an active (probably slightly anxious) mode, although the anxiety can be exciting and pleasurable. It’s a mode which we’re probably a little impatient, if only with ourselves. It has a little tension in it, not much humor. It’s a mode in which we’re very purposeful, and it’s a mode in which we can get very stressed and even a bit manic, but not creative.

By contrast, the open mode, is relaxed… expansive… less purposeful mode… in which we’re probably more contemplative, more inclined to humor (which always accompanies a wider perspective) and, consequently, more playful. It’s a mood in which curiosity for its own sake can operate because we’re not under pressure to get a specific thing done quickly. We can play, and that is what allows our natural creativity to surface.

But let me make one thing quite clear: we need to be in the open mode when we’re pondering a problem but once we come up with a solution, we must then switch to the closed mode to implement it. Because once we’ve made a decision, we are efficient only if we go through with it decisively, undistracted by doubts about its correctness.

Once we’ve taken a decision we should narrow our focus while we’re implementing it, and then after it’s been carried out we should once again switch back to the open mode to review the feedback rising from our action, in order to decide whether the course that we have taken is successful, or whether we should continue with the next stage of our plan. Whether we should create an alternative plan to correct any error we perceive. And then back into the closed mode to implement that next stage, and so on.

How to get into the open mode:

1. Space

Let’s take space first: you can’t become playful and therefore creative if you’re under your usual pressures, because to cope with them you’ve got to be in the closed mode. So you have to create some space for yourself away from those demands. And that means sealing yourself off. You must make a quiet space for yourself where you will be undisturbed.

2. Time

It’s not enough to create space, you have to create your space for a specific period of time. You have to know that your space will last until exactly (say) 3:30, and that at that moment your normal life will start again.

And it’s only by having a specific moment when your space starts and an equally specific moment when your space stops that you can seal yourself off from the everyday closed mode in which we all habitually operate.

It’s easier to do trivial things that are urgent than it is to do important things that are not urgent, like thinking. And it’s also easier to do little things we know we can do, than to start on big things that we’re not so sure about.

So when I say create an oasis of quiet know that when you have, your mind will pretty soon start racing again. But you’re not going to take that very seriously, you just sit there (for a bit) tolerating the racing and the slight anxiety that comes with that, and after a time your mind will quiet down again.

But don’t put a whole morning aside. My experience is that after about an hour-and-a-half you need a break. So it’s far better to do an hour-and-a-half now and then an hour-and-a-half next Thursday and maybe an hour-and-a-half the week after that, than to fix one four-and-a-half hour session now.

3. Time

Yes, I know we’ve just done time, but that was half of creating our oasis. Now I’m going to tell you about how to use the oasis that you’ve created.

Well, let me tell you a story. I was always intrigued that one of my Monty Python colleagues who seemed to be (to me) more talented than I was {but} did never produce scripts as original as mine. And I watched for some time and then I began to see why. If he was faced with a problem, and fairly soon saw a solution, he was inclined to take it. Even though (I think) he knew the solution was not very original.

Whereas if I was in the same situation, although I was sorely tempted to take the easy way out, and finish by 5 o’clock, I just couldn’t. I’d sit there with the problem for another hour-and-a-quarter, and by sticking at it would, in the end, almost always come up with something more original. My work was more creative than his simply because I was prepared to stick with the problem longer.

The most creative professionals always played with a problem for much longer before they tried to resolve it, because they were prepared to tolerate that slight discomfort and anxiety that we all experience when we haven’t solved a problem.

Now the people I find it hardest to be creative with are people who need all the time to project an image of themselves as decisive. And who feel that to create this image they need to decide everything very quickly and with a great show of confidence. Well, this behaviour I suggest sincerely, is the most effective way of strangling creativity at birth.

4. Confidence

When you are in your space/time oasis, getting into the open mode, nothing will stop you being creative so effectively as the fear of making a mistake. Now if you think about play, you’ll see why. To play is experiment: “What happens if I do this? What would happen if we did that? What if…?”

The very essence of playfulness is an openness to anything that may happen. The feeling that whatever happens, it’s ok. So you cannot be playful if you’re frightened that moving in some direction will be “wrong” — something you “shouldn’t have done.”

So you’ve got risk saying things that are silly and illogical and wrong, and the best way to get the confidence to do that is to know that while you’re being creative, nothing is wrong. There’s no such thing as a mistake, and any drivel may lead to the break-through.

5. Humor

Well, I happen to think the main evolutionary significance of humor is that it gets us from the closed mode to the open mode quicker than anything else.

I think we all know that laughter brings relaxation, and that humor makes us playful, yet how many times important discussions been held where really original and creative ideas were desperately needed to solve important problems, but where humor was taboo because the subject being discussed was {air quotes} “so serious”?

No, humor is an essential part of spontaneity, an essential part of playfulness, an essential part of the creativity that we need to solve problems, no matter how ‘serious’ they may be.

Well, look, the very last thing that I can say about creativity is this: it’s like humor. In a joke, the laugh comes at a moment when you connect two different frameworks of reference in a new way.

Example: there’s the old story about a woman doing a survey into sexual attitudes who stops an airline pilot and asks him, amongst other things, when he last had sexual intercourse. He replies “Nineteen fifty eight.” Now, knowing airline pilots, the researcher is surprised, and queries this. “Well,” says the pilot, “it’s only twenty-one ten now.”

We laugh, eventually, at the moment of contact between two frameworks of reference: the way we express what year it is and the 24-hour clock. Now, having an idea, a new idea, is exactly the same thing. It’s connecting two hitherto separate ideas in a way that generates new meaning.

Connecting different ideas isn’t difficult, you can connect cheese with motorcycles or moral courage with light green, or bananas with international cooperation. You can get any computer to make a billion random connection for you, but these new connections or juxtapositions are significant only if they generate new meaning.

So as you play you can deliberately try inventing these random juxtapositions, and then use your intuition to tell you whether any of them seem to have significance for you. That’s the bit the computer can’t do. It can produce millions of new connections, but it can’t tell which one smells interesting.

So, to summarise: if you really don’t know how to start, or if you got stuck, start generating random connections, and allow your intuition to tell you if one might lead somewhere interesting. 6

Humor

When James Thurber described humour (or humor) as “emotional chaos remembered in tranquility” he was only pointing out that things that seem very important at the time usually aren’t, and that it’s not unkind to laugh at temporary upsets, especially when they’re our own. In fact, it’s rightly considered healthy to be able to laugh at oneself, and we all much prefer people who do not take themselves “too seriously.”

A good sense of humour is the sign of a healthy perspective, which is why people who are uncomfortable around humour are either pompous (inflated) or neurotic (oversensitive).

Pompous people mistrust humour because at some level they know their self-importance cannot survive very long in such an atmosphere, so they criticise it as “negative” or “subversive.” Neurotics, sensing that humour is always ultimately critical, view it as therefore unkind and destructive, a reductio ad absurdum which leads to political correctness. 1

Never Stop Learning

As a general rule, when people become absolutely certain that they know what they’re doing, their creativity plummets. This is because they think they have nothing more to learn. Once they believe this, they naturally stop learning and fall back on established patterns. And that means they don’t grow.

The trouble is that most people want to be right. The very best people, however, want to know if they’re right. That’s the great thing about working in comedy. If the audience doesn’t laugh, you know you’ve got it wrong. 2

Suppressed Anger Is Funny

It is suppressed anger that is funny. If Basil ever fully lost his temper, and started screaming at people, the audience wouldn’t laugh. It’s when he tries to control it, but shows tell-tale signs that he is failing (profitless sarcasm, smacking his own bottom, flogging a car, speaking in an exaggeratedly deliberate way, suddenly slamming down a phone), that he is funny. Real anger can work in real life; it won’t work as comedy. Funny anger is ineffectual anger. 1

Extending Pauses For A Bigger Laugh

I watched Ronnie Corbett like a sparrowhawk, because he played with his timing, sometimes taking risks by extending pauses longer than I would ever have dared, and I noticed how, by waiting this fraction more, he would build the tension just before he triggered his line, and get a bigger laugh as a result. 1

Sunday Museletter (Free)

Ignite your creativity with hand-picked weekly recommendations in music, film, books, and art — sent straight to your inbox every Sunday.

Next up: Charlie Kaufman on authenticity and screenwriting.

References

- So, anyway…: the autobiography, by John Cleese. 2015.

- Creativity: A Short and Cheerful Guide, by John Cleese. 2020.

- John Cleese Interview, The Guardian.

- John Cleese talks books, Pen Factor.

- Feature Article, The Week.

- Creativity in Management – John Cleese Speech.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.