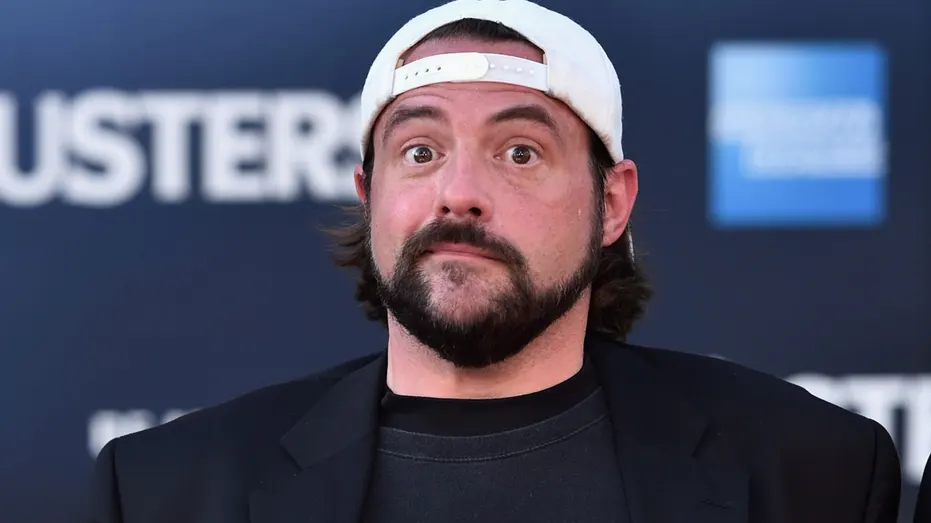

Kevin Smith on his advice for aspiring filmmakers, favourite films, the value of your unique voice, and “good enough” filmmaking.

A brief overview of Kevin Smith before delving into his own words:

| Who (Identity) | Kevin Smith is an American filmmaker, actor, comedian, and writer, renowned for his contributions to independent cinema. He is best known for his witty dialogue, humor, and for creating the “View Askewniverse,” a shared universe populated by recurring characters across multiple films. He first gained attention with his low-budget indie film Clerks in 1994. |

| What (Contributions) | Smith is a pivotal figure in the independent film scene of the 1990s. His debut film Clerks became a cult classic and launched his career. Smith’s View Askewniverse includes films like Mallrats, Chasing Amy, Dogma, Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, and Clerks II. He is also known for his candid, humorous podcasts, comic book writing, and as the creator of Comic Book Men. |

| When (Period of Influence) | Smith’s influence started in the early 1990s with the release of Clerks, which became a major success at the Sundance Film Festival. His films and public presence have remained relevant over several decades, and he continues to direct, write, and produce films into the 2020s, as well as hosting numerous podcasts and live events. |

| Where (Geographic Focus) | Born and raised in New Jersey, Kevin Smith’s films often feature settings in suburban areas of New Jersey, particularly Red Bank and Leonardo, which are close to his personal roots. His influence, however, extends across the U.S. and globally through his films, podcasts, and public speaking engagements. |

| Why (Artistic Philosophy) | At the heart of Smith’s artistic philosophy is a focus on dialogue and humor. He often writes characters who are conversational and relatable, blending humor with reflections on life, love, and personal identity. Smith’s films celebrate everyday, ordinary characters, especially from geek and fan subcultures, and emphasize the value of friendship, community, and personal expression. |

| How (Technique and Style) | Smith’s style is defined by quick-witted, snappy dialogue, often filled with pop culture references. His directing style is simple and character-focused, with a reliance on long takes and static shots to emphasize the conversations. Smith’s budget-conscious approach to filmmaking, especially in his early works, became a hallmark of the DIY ethos of independent cinema in the 1990s. He is also known for reusing characters, primarily Jay and Silent Bob, across his films, creating a unique interconnected cinematic world. |

Quotes & Excerpts

This post features a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with references found at the end of the article.

Secrets To A Successful Life

It doesn’t even take TALENT to do what I did; I’m living proof of that. All you need to do is identify what you love to do and monetize that.

If you like dogs, monetize your canine interest. Lazy people like me will always pay someone to wash his dog(s). Some people will pay you to babysit ’em!

If it never feels like work, it’s NOT work. Life is mutable; the rigidity of working for someone else doesn’t allow for much flexibility. So create your own ideal universe. That’s all I’ve been doing now for nearly 20 years.

I didn’t want to have to go to my relatives houses if I didn’t want to – as my parents would make me do when I lived with them. So I wanted to find a way to be able to say “I’m not going” for which I wouldn’t catch shit. Being a filmmaker seemed like an excellent excuse to not go to relatives houses if I didn’t want to.

The secret to a successful life is hardly a secret; it requires you to be self-centered. So long as it’s not at the expense of others, make yourself the center of your universe. You only get to do this ONCE, so try to take as much stress out of the process as you can. Why stress out in some office wearing clothes you hate, when the REAL stress lies ahead, as we face an inescapable grave. Doubt I’m gonna go quietly into that good night, so I’ll save the stress for then.

Sadly, as far as I’ve learned, we can do NOTHING to alter death; it’s GONNA happen. But life? We can shape & change the fuck out of life!

Sometimes, the path isn’t direct. It’s like folks who start movie websites: they just love movies. Not sure what their end-game’s gonna be, but writing about them & hosting trailers is a start, right?

For some, the end-game will be to make a film. For some, just having people read what they have to say about a subject they love is good enough. Regardless, the smart ones will always find a way to earn off it. Because once you’ve got a taste for working for yourself, doing what you love doing? You’ll work 10x as hard as any brick-layer or paralegal, but you’ll NEVER feel it, never recognize it. And let the cranks cat-call from the sidelines; they lack balls of any element, let alone brass.

Ignore the flock of naysayers, focus on what you love to do, and earn off it. And remember: Opinions don’t pay rents. If you get paid to do what you love, you’re a pro.

The work is long & will take you away from lots of other people & things. But you will never know/feel/realize it’s work – not until you look back. This Sundance marks 17 years since the CLERKS debut changed my life.

But from the moment we got our foot in the door, the workload intensified a thousand fold. And I never noticed – because I loved it so much. For 15 of those 17 years, I didn’t stop. Cranks will tell you I’ve been living off CLERKS forever, but that’s dismissive self-deception.

We got our foot in the door & I never stopped. And while the changes were imperceptible to some, each time out, we worked a little harder at developing the various muscles of storytelling. In that analogy, RedState is the most physically fit of all the stories I’ve told. It’s the sum total of nearly two decades of hard work (for which, most times, I was handsomely overcompensated, monetarily & otherwise).

And it never felt like work when we were crafting them. What made them feel like work was slugging it out with jackasses over opinion, or getting by the fear-driven gatekeepers who finance, market, or rate the stories I’ve tried to tell. Like hockey, film used to be a simple, fun game that grown-up kids loved to play. Then, someone figured out how to make a buck off it. Now it’s a business.

Rage against the darkness all you want: at the end of the day, it’s called the movie BIZ. Bitching about that fact’s akin to bitching about sharks in the ocean: if you’re stepping into the surf, you’re stepping into the food chain. Don’t be a dummy: make sure you’re in a boat.

Start with a small boat and one day, you realize you’re Cap’n Stubbing. Or in my case, Cap’n Crunch. Then you can put a dog in a sailor suit & cock-block French pirates.

It’s summed up on this dopey yoga wall hanging the wife has in the house that I only really understood this year: MAY YOU REALIZE YOUR DIVINITY IN THIS LIFETIME. That’s worth working for.

It took me 40 yrs, but I finally realized my divinity in this lifetime. Not talking “Clapton is God” or Lennon’s “We’re bigger than Jesus” when I say this: but we can each …hell, we SHOULD… each make of ourselves… a god, for lack of better expression. And I’m not talking the drag some kid into the woods and cut his heart out bullshit; I’m talking about finding for ourselves the same reverence the faithful reserve for the divine.

And what better to shoot for than mortal divinity? And not that angry god bullshit, either: if the X-Men taught me anything, God loves & man kills. 1

Favourite Films

Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975)

JFK (Oliver Stone, 1991)

A Man For All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966)

Do The Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

The Last Temptation of Christ (Martin Scorsese, 1988) 2

Raising Arizona (Joel and Ethan Coen, 1987)

The Business (Nick Love, 2005)

Coal Miners Daughter (Michael Apted, 1980)

Labyrinth (Jim Henson, 1986) 3

Is Film School Worth It?

Absolutely not. It also depends on what you want to do. I wanted to write and direct. I really didn’t want to direct all that much—basically I wanted to write. But I soon realized that to get the exact vision you’ve written up on screen, you have to take charge of the script, so that’s where the directing end came from. But they can’t teach you writing and directing in film school. They can teach you format, but you can teach yourself that by looking at scripts. In terms of directing, either you’re good with people or you’re not good with people. 4

Importance Of Writing Your Own Films

I think more as a writer. I just don’t think I have a directorial instinct. I think it all comes from writing and that’s why the films don’t have a fantastic visual style to them. In fact, there’s no visual style to them. There’s a lot of banter and a lot of talk.

In my estimation, writing is the best path to directing. Because that’s really all I know, but again I came from a different school of thought in terms of directing. I come from the school of thought that you write what you direct.

Sometimes I can’t figure out the people who don’t write what they direct. I mean traditionally that’s pretty much what the director is, some guy who’s directing someone else’s script, but I always have a problem with that. There are people like Martin Scorsese, people of that cut…and you’re just, “wow.” They can take somebody else’s script and make something tremendous with it.

As far as me, I just don’t. I can never visualize people asking, “Would you direct someone else’s script?” I just don’t see how I could. I’m not a visual stylist. The only reason I can direct what I write is because I’ve written it; I know how it should sound. 4

What Is Good Dialogue?

Good dialogue for me is when it just pops. Nothing can be happening in a movie, and two people can be sitting in a room for the whole flick and as long as the dialogue pops, it’s there. It’s back and forth to me. It’s banter. Right now to me, good dialogue is something I listen to and go, “Gee, I wish I’d written that.” That feeling’s few and far between, that you ever hear stuff like that.

Jerry Maguire is a good example. Larry Flynt’s another one. Fargo, of course. 4

Advice for Aspiring Filmmakers

You don’t need anyone of significance to look at your script. Just make it yourself. It’s what I did with Clerks: I had a script but I didn’t think anyone would financially back it (and I had zero connections anyway). So I just made the flick on my own credit cards. That was 20 years ago. Shit’s even easier and cheaper to do now, with the current tech. Don’t wait for help: help is never coming. Just do it yourself.

And if it’s too expensive to do it yourself, then start making changes to your script and lower your expectations. You can either have an awesome screenplay that never leaves your laptop or you can have a film that’s less than you hoped it’d be, but still a far better expression of self than your light hidden under a bushel, waiting for assistance that’s never coming. You can say ‘easier said than done’ to lots of people – just not the guy who made Clerks. He knows better. 5

There’s a fine line you’ve got to walk as a filmmaker—or, if you dare to call yourself an artist—and you’re listening to that voice inside you. You know how it should be, you know what it should look like. You have a very specific vision in mind. I think there is an acceptable amount of that—the filmmaker should be allowed to get their image on the page or on celluloid.

But it doesn’t include abusing people around them by any stretch of the imagination. You have to have a reasonable amount of unreasonability to even become a filmmaker. Reason would dictate, “Hey man, you’re not from Los Angeles, you don’t work near a movie studio, you weren’t born into this business, you can’t be a filmmaker—that’s for other people.” But you have to be unreasonable enough to say, “No, it doesn’t have to be that way.” Not unreasonable like, “I’m going to change the world,” but just enough to say, “I’m going to do it, screw what they say.”

You need a bit of that unreasonability, but you also need to know when to let things go and which hills you’re willing to die on. That’s what filmmaking is. As a director, your job is to answer a never-ending series of questions because everyone’s asking you questions. They’re trying to make your vision come to life, they’re trying to help you. You always have to have an answer for them.

They come up to you, and you have to give them an answer right away. You can’t sit there and go, “Umm, I mean, is that important?” If you hesitate, they’ll smell blood in the water and think, “This guy doesn’t have a clue.” As long as you’ve got an answer for them, it doesn’t matter if it’s right or wrong—because that’s all subjective, right? At the end of the day, you just have to know your job and be able to tell them what you want. They’re trying to help you.

Now, if you’re making a movie for $20,000 or $10,000, there might be things in your script or in your head that you feel are essential. You might think, “Without this, there’s no point in making the movie.” But you have to be willing to let things go. You have to be willing to make concessions. If someone’s writing you a check, that’s great, but if it’s not a big enough check to do what you need to do, you have to decide: Do you hold on to that money until you have something that fits the budget, or do you tailor your project to fit those financial confines?

Some filmmakers get really tight about that. You meet filmmakers who refuse to cut their movie—they’ve got a two-and-a-half-hour cut, and they say, “It’s all essential.” They think, “If I take this out, the whole puzzle falls apart.” 6

Why Editing Is Essential

But as a filmmaker, your job is to entertain, get the message across, and move people. You need to give them something to think about, something intangible they can take away from the theater, something here (in the head) or here (in the heart). But you have to do it as economically as possible. You can’t make them sit there longer than necessary, or the magic starts to dissipate. You sit there and watch a magician for two hours, and eventually, you’ll figure out where the rabbit came from. But if it’s only 15 minutes, you’re still amazed, thinking, “Where did that rabbit come from?”

That’s what it’s about—leaving them wanting more. Make the illusion happen, but if your movie is too chunky, flabby, or bloated, it loses its impact. You can say what you want about the movies I’ve done, but all of my movies are cut to the bone. I pride myself on that. I kill my darlings, and that’s a big part of editing.

A lot of people say, “You have to learn how to kill your darlings.” I don’t just kill them—I cut their throats, pull their heads off, and suck the marrow from their bones. That’s how serious I am about the cut. It’s not about, “Oh, but I really want this scene in there because I like it.” It’s about telling the story tightly and sharply. Get in front of the audience, tell the story, and get out.

If it works, great. If it doesn’t, well, I’ll get another chance down the road. But I’m not going to let it fail because it was flabby, bloated, or self-indulgent. I’m not going to be Tim Burton or Martin Scorsese. Tim makes long movies, and Scorsese’s films just feel long, but they’re not. 6

Avoiding Filmmaking Pitfalls

When it comes to preparing for a movie, some of the pitfalls people can avoid might be little things. It could be energy being focused, or having enough time. Honestly, the biggest pitfall is that you’ll never have enough time or money. It doesn’t matter what your budget is. Whether you have $3 million or $300 million, every filmmaker and every producer always has the same complaint: not enough time and not enough money. Even if you’ve got more money, you think that’ll fix it, but it just winds up being the same problem—economy of scale.

So, don’t worry about that stuff. This is what you need to think about: be prepared. If you’re starting for the first time and you’ve never done this before, rehearse the hell out of everything. For Clerks, Mallrats, and Chasing Amy, we rehearsed for a month before we went near a set. That way, your take ratio is going to be low. Some people may ask, “What does that matter in the age of digital video?” Back when you were shooting film, it was expensive to process film. Time is money on a movie set, so if you can accomplish it in one take, move on. 7

“Good Enough” Filmmaking

The story of my life, and I’ve told it before publicly so this might not be news to some, is how I’ve been able to keep doing what I’ve been doing for 30 years. People might say, “I hate him, why does he keep working?” This is why: I don’t strive for excellence. I’m no Christopher Nolan. Believe me, every critic will tell you that. Christopher Nolan strives for excellence. I, from the beginning of my career with Clerks forward, was never like, “Let’s make it perfect.” If I was striving for perfection, I don’t think I’d have ever made my first film yet. I’d still be sitting there frozen, asking myself, “Will it be good enough?”

“Good enough” will take you very far. “Good enough” has taken me 30 years. On the set of Clerks, we’d shoot a scene, and I’d say, “Cut. Alright, that’s good enough. Let’s move on.” “Good enough” has gotten me here, all the way to this chair. “Good enough” will get you as far as you need to go.

Now, I know that’s probably not “winner talk.” If you want to win an Oscar, you’ve got to leave it all on the table. You’ve got to make those movies where Leonardo DiCaprio fights a bear in the snow because everyone’s got to be miserable in order for it to read right. But I’m not that guy. I’m not that committed to it. I just like to make pretend, maybe get a little money for it, and that’s it.

I can’t authentically go in with that mentality where everything has to be perfect at the cost of everybody else. There are directors who do that, and I guess I respect them a little bit, but I wouldn’t do that to my crew. Those movies are successful because they’ve got a vision, a drive, and the passion of a filmmaker. If I ever tried to make one of those films, it wouldn’t happen. Number one, I don’t have the talent. Number two, I don’t have the patience. And number three, I can’t do that to other people.

I want people leaving my set saying, “I had a good time.” That’s how I keep my budgets low. The crew comes back and works for scale because they know they’re going to have a good time on set. They know they’ll have happy memories. “Good enough” gets me to the set. If I’ve rehearsed enough before we shoot, when I’m on set, it’s one or two takes tops, and then I say, “Good enough, moving on.” All that saved time adds up—and that’s money.

Striving for perfection is something you can aim for at some point in your career, I guess. But I never have. And I’ve been doing this for 30 years. Some people out there, like the Letterboxd crowd, might be disgusted by that idea, thinking, “Oh, he doesn’t even try.” But I’ve been doing this for 30 years, so clearly, I show up and deliver. I just don’t make everyone’s life miserable to do it.

If you’ve got a vision or an idea of where you’re going, why not have a good time doing it? Otherwise, what’s the point? If people are miserable on a set when you’re making pretend for a living, everybody has failed. You shouldn’t be doing this if it’s not fun. It should be fun. It’s make-believe for a living.

I get that some people think, “Art is pain, and pain is good,” but not really. This is an art form, don’t get me wrong, but it doesn’t have to be painful. It’s very cathartic, and some folks can’t pivot away from that belief that it has to be painful. I don’t believe in that. I’m the guy who says, “That’s good enough, let’s move on.” Every one of my movies is “good enough.” They don’t have to be great.

I saw somebody on Twitter the other day saying something like, “There’s one or two really brilliant ideas in this movie, and the rest is just some horseshit.” And I’m like, yeah, that’s it. You don’t have to keep watching my films if you don’t like that kind of thing, but I’m lucky I got one or two good ideas in the horseshit.

If you’re an indie filmmaker out there thinking, “Nobody’s ever heard my story, they’ve never heard my voice, they’ve never seen what I can do,” then use me as your example.

If you’re sitting there hating on me, thinking, “Kevin Smith makes the same movie every time—30 years in the business and all he’s done is make Clerks and Jay and Silent Bob,” well, now’s your time to shine. Don’t waste your time hating on me. Use me as your stepping stone. If that “talentless idiot” can do it, then you can do it too.

Now is the time for another indie filmmaking movement. It feels like there’s frustration among real filmmakers. I know people who make millions to make movies, and now they’re sitting on their asses because nobody’s making movies right now. Could you imagine if the only way you got to do your show was if someone told you, “Okay, now you can go”? No, you enjoy the independence of saying, “This podcast is going to happen when I want it to happen.” You’re your own boss.

A lot of people never figured out how to do that. They never came from indie film, so they couldn’t pivot back to indie film. They’ve just been spoiled by working for a studio. Now, with studios not making anything, they’re lost, like, “What do I do?” I’ve always been able to pivot back to indie film, and I feel like I’ve been in indie film for a while now. Everyone knows every variation of the story I could possibly tell. Every once in a while, I’ll whip out something weird like Tusk, but generally speaking, people know me for the Jay and Silent Bob movies.

Now is the time for an indie filmmaker to come out and say, “Here’s a story nobody’s ever heard.” If you’re a filmmaker, make your film. Now is the time to take your shot because there’s an empty space in the marketplace for that type of storytelling. 7

Direct-to-Consumer Filmmaking

Everything has gone mainstream. Streaming is now mainstream. People telling offbeat stories on streaming platforms are essentially working for studios. When I started in indie film, we were outside of Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox, and Paramount saying, “Well, they’ll never let us play.” But that didn’t mean we couldn’t do it on our own. The streamers are the gatekeepers now. So if Netflix isn’t giving you a shot, great—go do it on your own. Hang your own shingle. People are hungry for unique, independent stories.

It’s a good idea to sell directly to consumers. [Talking to comedian Theo Von] Imagine you go on a comedy tour, but instead of just stand-up, you show a movie first. You say, “Hey, welcome, we’re going to watch the movie, and then we’ll talk about it after.” You step away for 90 minutes, come back, and do crowd work—answering questions.

You have the ability to do that. Why do you need anybody else? You’ve already built an audience. You could go into an AMC theater like Taylor Swift and say, “I guarantee you I can make people show up to see this movie because my podcast has 200 million downloads.” Even if AMC says no, you go to Fathom Events and say, “I want to put my movie in theaters for two days.” You could make $10 million and people would write stories about how smart you are.

You don’t need anyone, Theo. You already have the distribution mechanism in place. You’re a loaded gun—you just have to point your audience in the right direction. Point them to the next show or live gig. If you make a movie with David Spade, don’t sell it until you’ve milked it for everything you personally can, just like you juice your own stand-up shows. Then, after you’ve gotten everything out of it, you can sell it to a streamer or a home video company.

The big mystery in this business is how to get people to show up. You already know how to get people to show up. Now, you’re just saying, “When you show up this time, we’re going to do things a little differently—we’re going to show you a movie first, then do a comedy show after.” Charge the same price, and all that money goes straight to the flick. 7

The Economics of Independent Film

If we’re talking about a Jay and Silent Bob type movie or Clerks 3, I can get between $8 and $10 million. The Clerks 3 movie cost $3 million to make, and that’s coming out on September 13th. Saban financed that, just like they financed Jay and Silent Bob Reboot a few years ago.

You can make your money back and a little extra. I think that’s how I’ve managed to stay in the business for as long as I have—three decades, well past my “expiration date.” I can always pivot to making a less expensive movie. A lot of people say, “It’s got to be $20 million or nothing.” I’m the opposite—I say, “We’ll do it for $3 million,” whether we can or not. We’ll cram it into that number.

It’s a privilege to be able to make a movie. It’s a weird proposition to ask someone for a lot of money just to make pretend. Most people are like, “Why don’t you just make pretend for free?” But I’ve realized my job is full of BS—it’s a pack of lies. What I try to do is artificially capture a moment that happened to me, a moment that made my head or heart feel something overwhelmingly wonderful. I think to myself, “If I can capture that and put it in a movie, other people will identify with that feeling.” 7

Facing The Reality Of Filmmaking

That’s why, after everything I do—whether it works or doesn’t work—there are two things I always say to myself. This is especially true if something didn’t work. The first thing I tell myself is, “You wanted this.” You changed the course of events to make this movie happen. You dreamed about this, somehow found millions of dollars, and convinced people to give up their time to make pretend with you. So, it doesn’t matter if it didn’t do what you wanted—it’s what you wanted, so you better enjoy it because it’s going to pass quickly.

The second thing I tell myself is, “What was the alternative?” Did you even have an alternative? Was the alternative to not do the thing? That’s not an option, because knowing I could do it and then not doing it would eat at me like a cancer. It’s sad when you know you can accomplish something, but you don’t do it because you’re afraid somebody won’t like it. 7

Overcoming Fear of Rejection

I’ve mentioned this before—dropping something you’ve created is scary. All creativity is, in a way, exposing yourself, making yourself vulnerable. But that’s why this is a safe environment. You’ve built a system for yourself where you don’t have to worry about rejection or hearing “no.” You’ve created a world of “yes” for yourself.

You don’t have that trepidation before every show because you’ve engineered it to be easy, like breathing. But when you’re making a movie, it’s different. There are way more people involved, and you’ve often been dying to make the movie for years. Sometimes, it takes a decade to get to that point where you’re finally on set. 7

The Magic of Charisma in Actors

Is there such a thing as “that person’s got it”? I absolutely believe there is. The ones with charisma are the people you always notice. They work a lot because they’ve got this natural charisma. It’s like the camera loves them. They know how to exist in front of the camera.

Take someone like Brad Pitt. That guy was born to be in front of a camera. You might argue that over time he learned how to be there, but even from the start, he had something special. First, he’s attractive, and in movies, we like to look at attractive people. But beyond that, he’s also very relaxed and natural. He never looks like he’s acting. It often feels like he’s underacting, but not in a bad way. He’s just there, not phoning it in, and not trying too hard.

He’s casual, always eating in movies, just sitting there, and yet, he’s a movie star because he’s dripping with charisma. So, when you reach that level, you’re casting people who are all Jedi in their own right. It’s just a matter of how powerful they are. Everyone at that level can do it, but some are exceptional. 7

Creating Iconic Moments

Here’s a story I’ve told a lot, so I apologize if you’ve heard it before, but when I was making Clerks 3—or the “4:30 movie” as I call it—I was shooting a scene with the three boys in the car. They were just goofing around, dancing while they drove, playing Chaka Khan’s “I Feel for You.” I went over to the car and said, “Kids, you’re just goofing around, dancing, do whatever you want—just make it iconic.” Then I walked away.

That really messed with their heads. Nick, who plays Bernie in the movie, came up to me and said, “That’s your direction? ‘Make it iconic’? That’s a little pressure, don’t you think?” I didn’t realize it at the time, but I have the benefit of 30 years of experience. I meant it when I said “make it iconic” because every decision they were making in real time was like dropping a stone in water and watching the ripple effect.

You never know what’s going to stand out years from now. Some weird little moment in the movie could become the thing people latch onto. I told them to make it iconic because someone will be watching that scene forever. Even if it’s a teenager today, they’ll sense the joy in that scene and connect with it. The moment may pass, and it’s just a Kevin Smith movie, but for someone out there, it could be their life preserver. It could be the thing that keeps them from drowning.

Movies are special in that way. They have a weird impact that’s different from anything else. It doesn’t matter what you do in other media—when it comes to movies, people cherish them because they’re an immersive experience. They’re in and out, a 90-minute to two-hour ride that takes you somewhere and then brings you back. Over the course of their lives, people turn to movies in times of trial or just for comfort.

When I told the kids to “make it iconic,” I was trying to emphasize that even the smallest moments in a movie can become important to someone. Every moment, even the ones that seem insignificant, could end up being the thing that keeps someone from drowning. 7

Adapting Expectations And Being Flexible

The best piece of advice I can give to anyone—especially young creatives—is to modify your expectations. There’s nothing wrong with that.

A lot of people in this business say, “You can’t compromise. You’ve got to stick to your vision as a director.” I’m supposed to talk about my vision and how we have to pursue it to the ends—where the means justify the ends in telling the story. But I don’t subscribe to that at all.

I’ve always been easy to work with because I know how to be pliable. If somebody’s giving you money to make a movie, you can’t just say, “Hey, screw you, man, I’ve got my story to tell.” You have to hear them out. If their input works, you adapt it into what you’re doing. If it doesn’t, you make your case and hope that maybe you can accommodate it somewhere down the line.

A lot of folks in my line of work would say, “You can’t ever compromise. Once you’ve got the money, forget them all.” But I don’t feel that way at all, man. Especially because my job is so goofy. If I could express myself in another way, it’d be so much cheaper. If I were a singer, I could open my mouth, and you’d hear how I felt. If I were a painter, I’d take a blank canvas, throw some color on it, and that would be my self-expression.

But I chose directing, which is the dumbest form of self-expression. It’s where you say, “I need to self-express. Give me $25 million and Ben Affleck, or I can’t do the job.” So, you find different ways to adapt over time. You become better, and yes, it does improve with time.

Some people might hear this and say, “You can’t compromise, you can’t bend, because if you bend, that’s when they get you.” But that’s not true at all. It’s not about bending or compromising; it’s about modifying expectations. 8

The Value of Your Unique Voice

Tell that story that is only yours. There’s a predilection toward people wanting to imitate what they’ve seen before or what is successful. Case in point: I wouldn’t have thought of making Clerks had I not seen Slacker, but those two movies don’t look a thing alike. They’re not alike. I didn’t think, “Well, I’ll just make Slacker again because that worked for him, so it’ll work for me.”

A lot of people think that way, where they’re like, “I want to do this because it worked over here, so obviously, this is the quickest path to success.” I don’t subscribe to that. After being in this business for nearly 30 years, based on my own experience and the experiences of those around me, I’ve learned this: Your story is your true value.

Your unique, only-you perspective—that’s your currency in this life. Nobody else has that. Your voice is your currency. That’s all you’ve got, man. If you’ve got good looks, enjoy them while they last, because you’ll get old and they’ll go away. If you’ve got money, try to hold on to it, because the world is constantly trying to take it from you. But you know what’ll never go away? Your perspective. It’s uniquely yours.

Your voice is your currency, and you need to spend that currency. A lot of people are afraid to do that because they think, “What if they don’t like my story?” Screw that. They want your story. Particularly now. This is something I’ve been saying for nearly 30 years, and I was saying it back when there was just an indie film movement. We live in a world now where content is king.

There are so many places to tell a multimedia story at this point, and you can even get paid to do it, which is a bonus. But don’t count on money. The best reward in this job—or any creative job—is self-expression. You get to do something that so many people in this world will never know: the joy of getting something off their chest and telling the world who they are.

My father sat in movie theaters with me for decades, watching movies, and never once thought, “We should tell our story.” It just never occurred to him. There are people out there who will never think that way. But for everyone in this room, it has occurred to us that what we have to say is so impossibly important that we’re willing to rearrange the universe to make sure people hear us.

We’ll travel from different countries to get educated, so we can go out there in the world and do that thing we know deep down we’re meant to do. If you’ve ever sat in a movie theater past the movie’s ending, reading the credits and not waiting for Captain America to pop up at the end, that means you’re a filmmaker who just hasn’t made a film yet. You’re deeply interested in this art form.

The most important piece of advice I can give you is to tell your story. That’s what’s going to make all the difference. It’s not about doing a superhero movie unless it’s a superhero movie nobody’s ever seen before, something with a unique perspective that’s yours. It’s not about doing something like Marvel or DC, though there’s nothing wrong with that. 9

In this world, make what you want to see cause at the end of the day there’s a bunch of people whose journey is not that dissimilar from yours. The more you do it the more it becomes the norm, and then the industry is no longer like a shitty boys club. You can’t sit in the darkness of a movie theatre and bitch that you don’t see yourself or your world represented up there if you’re not going to take the steps to be there and be that person. Nothing comes from complaints, things come from action. Take a little snapshot of your world, man. 10

Useful Resources

- Kevin Smith’s Secret Stash: The Definitive Visual History (Book) – A detailed visual chronicle of Kevin Smith’s career, featuring exclusive photos and behind-the-scenes content

- Tough Sh*t: Life Advice from a Fat, Lazy Slob Who Did Good (Book) – Kevin Smith’s bestselling autobiography with advice and stories about his journey in the film industry.

- Silent Bob Speaks: The Collected Writings of Kevin Smith (Book) – A collection of essays by Smith on pop culture, film, and life.

- Daredevil: Guardian Devil (Comic Book) – Smith’s critically acclaimed run on Marvel’s Daredevil.

- Batman: Cacophony (Comic Book) – A dark and gritty Batman story written by Smith.

- Green Arrow (Comic Book) – Smith’s influential run that brought Green Arrow back to life.

- Clerk (DVD)– A documentary exploring the journey from indie filmmaker to pop culture icon.

- Kevin Smith’s Complete Filmography (List) – Letterboxd

- Kevin Smith’s Favourite Films (List) – Letterboxd

Where To Start

Start with Clerks (1994), Kevin Smith’s low-budget debut that put him on the map. Then watch Chasing Amy (1997), where he gets more personal and digs into relationships. Finish with Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back (2001) for a dose of his raunchy, slapstick humor.

Get all three films in the Kevin Smith Blu-ray Collection.

Related Posts

Sunday Museletter (Free)

Ignite your creativity with hand-picked weekly recommendations in music, film, books, and art — sent straight to your inbox every Sunday.

References

- Kevin Smith’s Secrets To A Successful Life, Connected Comedy

- The five favourite films of Kevin Smith, Far Out Magazine

- Kevin Smith Gives Us a Movie Playlist (and Some Tears), Vulture

- Kevin Smith on Screenwriting, Part I, By Peter N. Chumo II, Creative Screenwriting

- Little advice from Kevin Smith, Reddit

- Kevin Smith – Great Filmmaking Advice, Gavin Michael Booth, YouTube

- How to Make Your Own Movie, According to Kevin Smith, Theo Von Clips, YouTube

- Kevin Smith clears misconceptions that hold up independent filmmakers, Inside Of You Clips

- VFS Storyteller’s Studio – Kevin Smith (AMA Live), VFS Originals

- Kevin Smith shares his advice for young filmmakers, Dazed Digital

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.