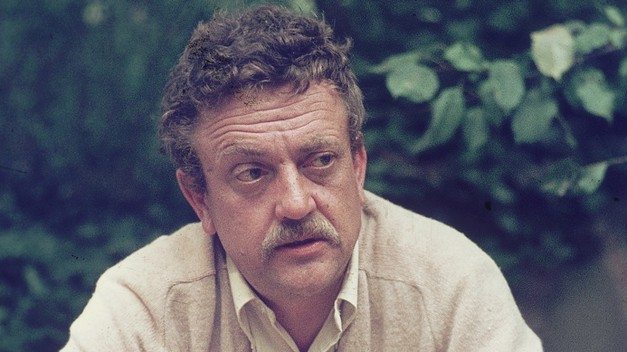

Kurt Vonnegut on loneliness, how to write with style, the purpose of art, his daily routine, and the importance of having other interests.

A brief overview of Kurt Vonnegut before delving into his own words:

| Who (Identity) | Kurt Vonnegut Jr., an American writer known for his satirical and science-fiction novels. He was a celebrated figure in American literature, recognized for his unique blend of humor, science fiction, and critical commentary on society. |

| What (Contributions) | Vonnegut’s works are known for their satirical, often darkly humorous exploration of modern society and human behavior. His most famous novels include “Slaughterhouse-Five,” “Cat’s Cradle,” and “Breakfast of Champions.” These works often addressed issues such as war, technology, and the human condition. |

| When (Period of Influence) | Vonnegut’s writing career spanned over 50 years, from the 1950s until his death in 2007. His works gained significant popularity during the 1960s and have continued to influence writers and thinkers. |

| Where (Geographic Focus) | Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, USA, Vonnegut’s work primarily reflects on American society and culture, though his influence is international. |

| Why (Artistic Philosophy) | Vonnegut’s philosophy in writing was marked by a skepticism of authority and a disdain for traditional narrative forms. He often combined science fiction elements with satirical and absurdist commentary, focusing on the absurdities and paradoxes of life. |

| How (Technique and Style) | Known for his distinctive narrative voice, Vonnegut’s style is characterized by simplicity, irony, and a blend of humor and gravity. He frequently used non-linear storytelling, science fiction elements, and metafictional techniques to challenge readers’ perceptions of reality and fiction. |

This post is a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with citations found at the end of the article.

Write For One Person

Every successful creative person creates with an audience of one in mind. That’s the secret of artistic unity. Anybody can achieve it, if he or she will make something with only one person in mind. 1

Loneliness

We are so lonely because we don’t have enough friends and relatives. Human beings are supposed to live in stable, like-minded, extended families of fifty people or more.

Marriage is collapsing because our families are too small. A man cannot be a whole society to a woman, and a woman cannot be a whole society to a man. We try, but it is scarcely surprising that so many of us go to pieces.

So I recommend that everybody join all sorts of organizations, no matter how ridiculous, simply to get more people in his or her life. It does not matter much if all the other members are morons. Quantities of relatives of any sort are what we need. 2

Practicing Your Skill Everyday

I think the value of a journal is simply that you write a lot. That’s just like Mark Spitz [Swimmer] spending his whole life in the swimming pool and that’s how he can do it better than anybody else. Keeping a journal means you write every day.

In the generation before mine, American writers mostly came up through journalism and often hadn’t even finished high school. If you work on a newspaper you write three, four, five, six stories a day about anything, and you’re writing and you’re writing and you’re writing. Your mind is saying “okay, I guess this is what we’re going to do and we’re going to do a lot of it”, and so you get skilled that way. 3

Sponsored: Canvas wall art paintings of nature and the cosmos.

Why Create?

When I used to be a speaker at colleges, I’d say, “Look, practice an art, no matter how badly or how well you do it. It will make your soul grow.” That’s why you do it. You don’t do it to become famous or rich. You do it to make your soul grow.

This would include singing in the shower, dancing to the radio by yourself, drawing a picture of your roommate or writing a poem or whatever. Please practice an art. Have the experience of becoming. It’s so sad that many public school systems are eliminating the arts because it’s no way to make a living.

What’s important is to have the experience of becoming, which is as necessary as food or sex. It’s really quite a sensation—to become.

You find out who you are that way. I used to challenge audiences, but I don’t face them much anymore. I’d say, “Write a poem tonight. Make it as good as you possibly can. Four, six or eight lines. Make it as good as you can. Don’t tell anybody what you’re doing. Don’t show it to anybody. When you’re satisfied it’s as good as you can make it, tear it up in small pieces and scatter those pieces between widely separated trash receptacles and you will find out you have received your full reward for having done it.”

It’s the act of creation which is so satisfying. 4

Daily Routine

In 1965, Vonnegut wrote a letter to his wife describing his schedule as a teacher in Iowa City:

In an unmoored life like mine, sleep and hunger and work arrange themselves to suit themselves, without consulting me. I’m just as glad they haven’t consulted me about the tiresome details. What they have worked out is this:

I awake at 5:30, work until 8:00, eat breakfast at home, work until 10:00, walk a few blocks into town, do errands, go to the nearby municipal swimming pool, which I have all to myself, and swim for half an hour, return home at 11:45, read the mail, eat lunch at noon.

In the afternoon I do schoolwork, either teach or prepare. When I get home from school at about 5:30, I numb my twanging intellect with several belts of Scotch and water ($5.00/ fifth at the State Liquor store, the only liquor store in town. There are loads of bars, though.), cook supper, read and listen to jazz (lots of good music on the radio here), slip off to sleep at ten.

I do pushups and sit-ups all the time, and feel as though I am getting lean and sinewy, but maybe not. Last night, time and my body decided to take me to the movies. I saw The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, which I took very hard. To an unmoored, middle-aged man like myself, it was heart-breaking. That’s all right. I like to have my heart broken. 5

In a 1969 interview with Robert Taylor of the Boston Globe Magazine:

I get up at 7:30 and work four hours a day. Nine to twelve in the morning, five to six in the evening. Businessmen would achieve better results if they studied human metabolism. No one works well eight hours a day. No one ought to work more than four hours.

How To Write A Short Story

1. Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

2. Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

3. Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

4. Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.

5. Start as close to the end as possible.

6. Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

7. Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

8. Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To heck with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages. 6

We Rarely Notice When We’re Happy

One of the things he [his Uncle Alex] found objectionable about human beings was that they so rarely noticed it when they were happy. He himself did his best to acknowledge it when times were sweet. We could be drinking lemonade in the shade of an apple tree in the summertime, and Uncle Alex would interrupt the conversation to say, “If this isn’t nice, what is?”

So I hope that you will do the same for the rest of your lives. When things are going sweetly and peacefully, please pause a moment, and then say out loud, “If this isn’t nice, what is?” 2

What It Takes To Be A Writer

I’ve heard that a writer is lucky because he cures himself every day with his work. What everybody is well advised to do is to not write about your own life — this is, if you want to write fast. You will be writing about your own life anyway — but you won’t know it.

And, the thing is, in order to sit alone and work alone all day long, you must be a terrible overreacter. You’re sitting there doing what paranoids do — putting together clues, making them add up… Putting the fact that they put me in room 471… What does that mean and everything?

Well, nothing means anything — except the artist makes his living by pretending, by putting it in a meaningful hole, though no such holes exist. 7

Plot

I guarantee you that no modern story scheme, even plotlessness, will give a reader genuine satisfaction, unless one of those old-fashioned plots is smuggled in somewhere. I don’t praise plots as accurate representations of life, but as ways to keep readers reading. When I used to teach creative writing, I would tell the students to make their characters want something right away—even if it’s only a glass of water. Characters paralyzed by the meaninglessness of modern life still have to drink water from time to time.

One of my students wrote a story about a nun who got a piece of dental floss stuck between her lower left molars, and who couldn’t get it out all day long. I thought that was wonderful. The story dealt with issues a lot more important than dental floss, but what kept readers going was anxiety about when the dental floss would finally be removed. Nobody could read that story without fishing around in his mouth with a finger.

Now, there’s an admirable practical joke for you. When you exclude plot, when you exclude anyone’s wanting anything, you exclude the reader, which is a mean-spirited thing to do. You can also exclude the reader by not telling him immediately where the story is taking place, and who the people are [and what they want].

And you can put him to sleep by never having characters confront each other. Students like to say that they stage no confrontations because people avoid confrontations in modern life. “Modern life is so lonely,” they say. This is laziness. It’s the writer’s job to stage confrontations, so the characters will say surprising and revealing things, and educate and entertain us all. If a writer can’t or won’t do that, he should withdraw from the trade. 1

Computers & TV

I hope you know that television and computers are no more your friends, and no more increasers of your brainpower, than slot machines. All they want is for you to sit still and buy all kinds of junk, and play the stock market as though it were a game of blackjack.

Forbes magazine asked me recently what my favorite technologies were, and I said a corner mailbox, my address book, and the Encyclopedia Britannica. The Britannica is arranged alphabetically, so you can find out all kinds of stuff, if you know your ABC’s. 2

Importance Of Having Other Interests

I think it can be tremendously refreshing if a creator of literature has something on his mind other than the history of literature so far. Literature should not disappear up its own asshole, so to speak. 8

How To Write With Style

Newspaper reporters and technical writers are trained to reveal almost nothing about themselves in their writing. This makes them freaks in the world of writers, since almost all of the other ink-stained wretches in that world reveal a lot about themselves to readers. We call these revelations, accidental and intentional, elements of style.

These revelations tell us as readers what sort of person it is with whom we are spending time. Does the writer sound ignorant or informed, stupid or bright, crooked or honest, humorless or playful–? And on and on.

Why should you examine your writing style with the idea of improving it? Do so as a mark of respect for your readers, whatever you’re writing. If you scribble your thoughts any which way, your reader will surely feel that you care nothing about them. They will mark you down as an ego maniac or a chowderhead — or, worse, they will stop reading you.

The most damning revelation you can make about yourself is that you do not know what is interesting and what is not. Don’t you yourself like or dislike writers mainly for what they choose to show or make you think about? Did you ever admire an empty-headed writer for his or her mastery of the language? No.

So your own winning style must begin with ideas in your head.

1. Find a subject you care about

Find a subject you care about and which you in your heart feel others should care about. It is this genuine caring, and not your games with language, which will be the most compelling and seductive element in your style.I am not urging you to write a novel, by the way—although I would not be sorry if you wrote one, provided you genuinely cared about something. A petition to the mayor about a pothole in front of your house or a love letter to the girl next door will do.

2. Do not ramble, though

I won’t ramble on about that.3. Keep it simple

As for your use of language: Remember that two great masters of language, William Shakespeare and James Joyce, wrote sentences which were almost childlike when their subjects were most profound. “To be or not to be?” asks Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The longest word is three letters long.Joyce, when he was frisky, could put together a sentence as intricate and as glittering as a necklace for Cleopatra, but my favorite sentence in his short story “Eveline” is this one: “She was tired.” At that point in the story, no other words could break the heart of a reader as those three words do.

Simplicity of language is not only reputable, but perhaps even sacred. The Bible opens with a sentence well within the writing skills of a lively fourteen-year-old: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.”

4. Have guts to cut

It may be that you, too, are capable of making necklaces for Cleopatra, so to speak. But your eloquence should be the servant of the ideas in your head. Your rule might be this: If a sentence, no matter how excellent, does not illuminate your subject in some new and useful way, scratch it out.5. Sound like yourself

The writing style which is most natural for you is bound to echo the speech you heard when a child. English was Conrad’s third language, and much that seems piquant in his use of English was no doubt colored by his first language, which was Polish. And lucky indeed is the writer who has grown up in Ireland, for the English spoken there is so amusing and musical. I myself grew up in Indianapolis, where common speech sounds like a band saw cutting galvanized tin, and employs a vocabulary as unornamental as a monkey wrench.In some of the more remote hollows of Appalachia, children still grow up hearing songs and locutions of Elizabethan times. Yes, and many Americans grow up hearing a language other than English, or an English dialect a majority of Americans cannot understand.

All these varieties of speech are beautiful, just as the varieties of butterflies are beautiful. No matter what your first language, you should treasure it all your life. If it happens to not be standard English, and if it shows itself when your write standard English, the result is usually delightful, like a very pretty girl with one eye that is green and one that is blue.

I myself find that I trust my own writing most, and others seem to trust it most, too, when I sound most like a person from Indianapolis, which is what I am. What alternatives do I have? The one most vehemently recommended by teachers has no doubt been pressed on you, as well: to write like cultivated Englishmen of a century or more ago.

6. Say what you mean

I used to be exasperated by such teachers, but am no more. I understand now that all those antique essays and stories with which I was to compare my own work were not magnificent for their datedness or foreignness, but for saying precisely what their authors meant them to say.My teachers wished me to write accurately, always selecting the most effective words, and relating the words to one another unambiguously, rigidly, like parts of a machine. The teachers did not want to turn me into an Englishman after all. They hoped that I would become understandable—and therefore understood. And there went my dream of doing with words what Pablo Picasso did with paint or what any number of jazz idols did with music.

If I broke all the rules of punctuation, had words mean whatever I wanted them to mean, and strung them together higgledy-piggledy, I would simply not be understood. So you, too, had better avoid Picasso-style or jazz-style writing, if you have something worth saying and wish to be understood.

Readers want our pages to look very much like pages they have seen before. Why? This is because they themselves have a tough job to do, and they need all the help they can get from us.

7. Pity the readers

They have to identify thousands of little marks on paper, and make sense of them immediately. They have to read, an art so difficult that most people don’t really master it even after having studied it all through grade school and high school—twelve long years.So this discussion must finally acknowledge that our stylistic options as writers are neither numerous nor glamorous, since our readers are bound to be such imperfect artists. Our audience requires us to be sympathetic and patient readers, ever willing to simplify and clarify—whereas we would rather soar high above the crowd, singing like nightingales.

That is the bad news. The good news is that we Americans are governed under a unique Constitution, which allows us to write whatever we please without fear of punishment. So the most meaningful aspect of our styles, which is what we choose to write about, is utterly unlimited.

8. For really detailed advice

For a discussion of literary style in a narrower sense, in a more technical sense, I recommend to your attention The Elements of Style, by William Strunk, Jr. and E.B. White. E.B. White is, of course, one of the most admirable literary stylists this country has so far produced.You should realize, too, that no one would care how well or badly Mr. White expressed himself, if he did not have perfectly enchanting things to say. 9

Love Stories

I try to keep deep love out of my stories because, once that particular subject comes up, it is almost impossible to talk about anything else. Readers don’t want to hear about anything else. They go gaga about love. If a lover in a story wins his true love, that’s the end of the tale, even if World War III is about to begin, and the sky is black with flying saucers.

I have other things I want to talk about. Ralph Ellison did the same thing in Invisible Man. If the hero in that magnificent book had found somebody worth loving, somebody who was crazy about him, that would have been the end of the story. Céline did the same thing in Journey to the End of Night: he excluded the possibility of true and final love—so that the story could go on and on and on. 1

Creative Process

I used to teach a writer’s workshop at the University of Iowa back in the ’60s, and I would say at the start of every semester, “The role model for this course is Vincent Van Gogh—who sold two paintings to his brother.”

I just sit and wait to see what’s inside me, and that’s the case for writing or for drawing, and then out it comes. There are times when nothing comes.

James Brooks, the fine abstract-expressionist, I asked him what painting was like for him, and he said, “I put the first stroke on the canvas and then the canvas has to do half the work.” That’s how serious painters are; they’re waiting for the canvass to do half the work. (Laughs) Come on. Wake up. 10

Reading Is A Skill

I was at a symposium some years back with my friends Joseph Heller and William Styron, both dead now, and we were talking about the death of the novel and the death of poetry, and Styron pointed out that the novel has always been an elitist art form.

It’s an art form for very few people, because only a few can read very well. I’ve said that to open a novel is to arrive in a music hall and be handed a viola. You have to perform.

To stare at horizontal lines of phonetic symbols and Arabic numbers and to be able to put a show on in your head, it requires the reader to perform. If you can do it, you can go whaling in the South Pacific with Herman Melville or you can watch Madame Bovary make a mess of her life in Paris.

All you have to do is sit there and look at a picture or a movie, and it happens to you. 10

Favourite Books

I consider anybody a twerp who hasn’t read the greatest American short story, which is “Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” by Ambrose Bierce. It isn’t remotely political. It is a flawless example of American genius, like “Sophisticated Lady” by Duke Ellington or the Franklin stove.

I consider anybody a twerp who hasn’t read Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville. There can never be a better book than that one on the strengths and vulnerabilities inherent in our form of government.

Want a taste of that great book? He says, and he said it 169 years ago, that in no country other than ours has love of money taken a stronger hold on the affections of men. Okay? 11

In a 1971 letter to Nanette, his youngest daughter:

I am going to order you to do something new, if you haven’t done it already. Get a collection of the short stories of Chekhov and read every one. Then read Youth by Joseph Conrad. I’m not suggesting that you do these things. I am ordering you to do them. 5

Humour

Humour is an almost physiological response to fear. Freud said that humour is a response to frustration—one of several. A dog, he said, when he can’t get out a gate, will scratch and start digging and making meaningless gestures, perhaps growling or whatever, to deal with frustration or surprise or fear.

And a great deal of laughter is induced by fear. I was working on a funny television series years ago. We were trying to put a show together that, as a basic principle, mentioned death in every episode and that this ingredient would make any laughter deeper without the audience’s realizing how we were inducing belly laughs.

There is a superficial sort of laughter. Bob Hope, for example, was not really a humourist. He was a comedian with very thin stuff, never mentioning anything troubling. I used to laugh my head off at Laurel and Hardy. There is terrible tragedy there somehow. These men are too sweet to survive in this world and are in terrible danger all the time. They could be so easily killed.

Even the simplest jokes are based on tiny twinges of fear, such as the question, “What is the white stuff in bird poop?” The auditor, as though called upon to recite in school, is momentarily afraid of saying something stupid. When the auditor hears the answer, which is, “That’s bird poop, too,” he or she dispels the automatic fear with laughter. He or she has not been tested after all. 11

What Life Is All About

I asked my son Mark what he thought life was all about, and he said, “We are here to help each other get through this thing, whatever it is.” I think that says it best. You can do that—as a comedian, a writer, a painter, a musician. He’s a pediatrician.

There are all kinds of ways we can help each other get through today. There are some things that help. Musicians really do it for me. I wish I was one, because they help a lot. They help us get through a couple hours. 10

Music & The Blues

No matter how corrupt and greedy our government and our corporations and our media and Wall Street and our religious and charitable organizations may become, the music will still be perfectly wonderful.

If I should ever die, God forbid, let this be my epitaph:

THE ONLY PROOF HE NEEDED

OF THE EXISTENCE OF GOD

WAS MUSIC.I like Strauss and Mozart and all that, but I would be remiss not to mention the absolutely priceless gift which African-Americans gave to the whole wide world when they were still in slavery. I mean “the blues.” All pop music today, jazz, swing, be-bop, Elvis Presley, the Beatles, the Stones, rock-and-roll, hip-hop, and on and on is derived from the blues.

The wonderful writer Albert Murray, who is a jazz historian among other things, told me that, during the era of slavery in this country, an atrocity from which we can never fully recover, the suicide rate per capita among slave owners was much higher than the suicide rate among slaves.

Al Murray says he thinks this was because slaves had a way of dealing with depression, which their white owners did not. They could play the blues.

He says something else which also sounds right to me. He says the blues can’t drive depression clear out of a house, but they can drive it into the corners of any room where they are being played. 2

Sunday Museletter (Free)

Ignite your creativity with hand-picked weekly recommendations in music, film, books, and art — sent straight to your inbox every Sunday.

Next up: Vincent van Gogh on the blank canvas.

References

- Kurt Vonnegut, The Art of Fiction No. 64, The Paris Review

- If This Isn’t Nice, What Is?, Kurt Vonnegut

- Kurt Vonnegut Interview – Part 1 [WFYIOnline]

- Interview by JC Gabel found in Kurt Vonnegut: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations

- Kurt Vonnegut: Letters, by Kurt Vonnegut

- Kurt Vonnegut on how to write a short story, YouTube

- NYU Guest Lecture, 1970

- Kurt Vonnegut, The Art of Fiction No. 64, The Paris Review

- How to Write With Style, published in the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers’ journal Transactions on Professional Communications in 1980.

- Interview by J.Rentilly, found in Kurt Vonnegut: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations

- A Man Without A Country, Kurt Vonnegut

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.