Pete Docter on his advice to new filmmakers, getting ideas, pixars style, writing characters, and how to overcome creative problems.

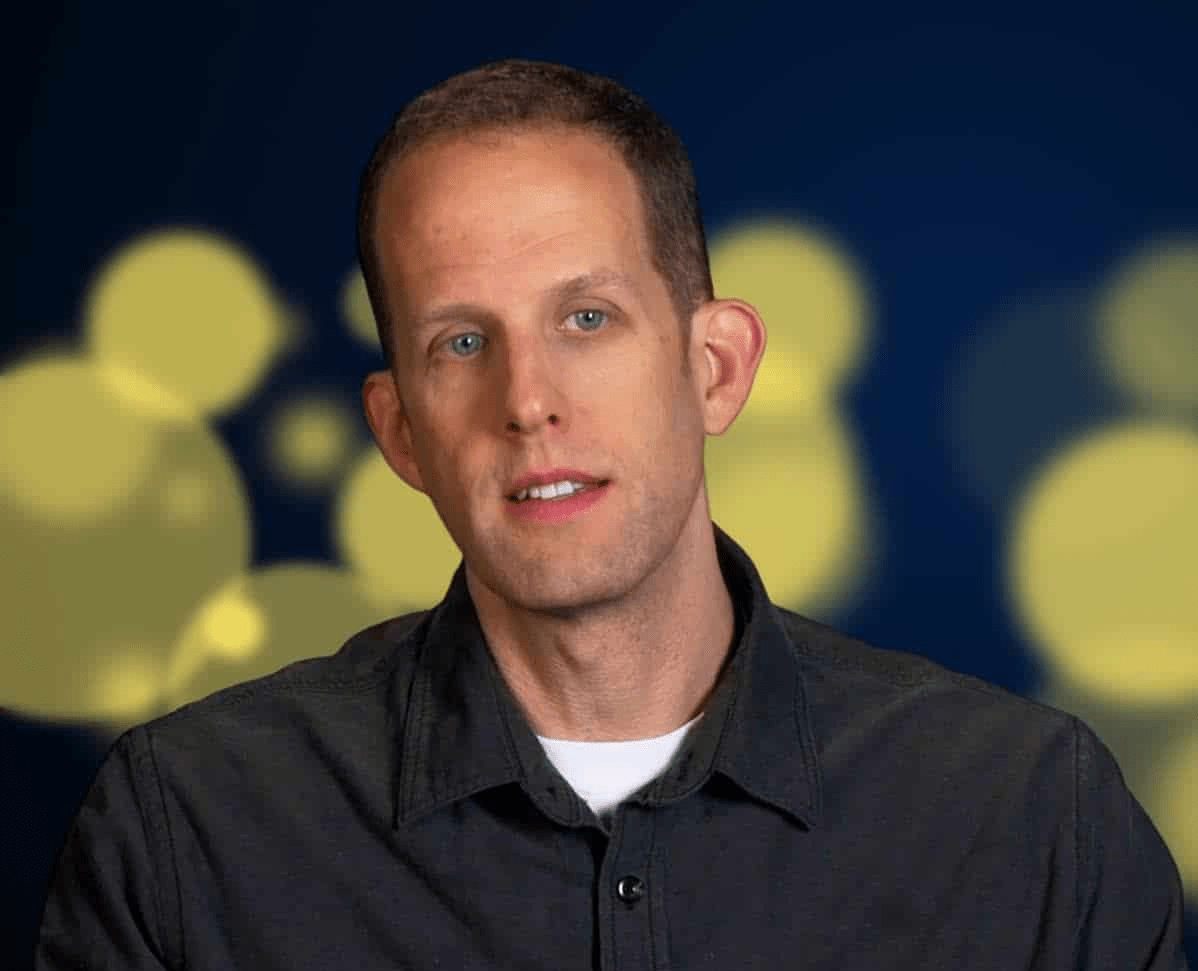

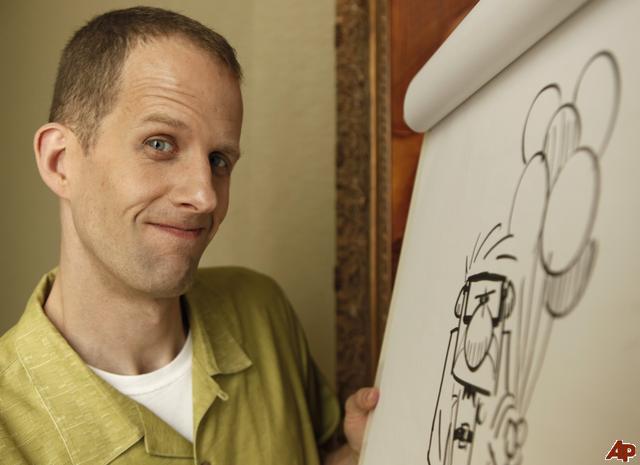

Pete Docter (b. 1968) is a Pixar storyteller behind Monsters, Inc., Up, Inside Out and Soul. Melding high-concept worlds with existential heart, the Minnesota animator became studio chief, championing family spectacle that asks what makes us fear, grieve and feel alive.

This post is a collection of selected quotes and excerpts from secondary sources used for educational purposes, with citations found at the end of the article.

Finding Originality In Your Work

Originality is hard to come by because the first stuff you get immediately when you come up with something is usually cliche, and you’ve probably seen it somewhere before, you’re pulling subconsciously from something else.

So the key is just keep digging. And make lists. This is weird, but a lot of times if you just start writing a solution to a problem, for example, how do I get this character out of a pit? He could climb out. Okay. That’s boring. I could use a ladder. Well there’s no ladder. You just keep making lists until you get down to like number 20 or so and then you’re like wow, that could be interesting. 1

Storytelling

The more particular and specific you are in the storytelling, the more generally it applies. If you try to generalize, then nobody really gets anything. But if you’re very specific and personal about it, it seems to resonate more. 2

Sponsored: Canvas wall art paintings of nature and the cosmos.

Advice To New Filmmakers

The first thing I say is do it. There’s really no excuses. With your iPhone, you can make movies. You know, you can cut stuff on your Mac, and with relatively small investment in money, you can start making your own stuff. And I always think of it like, you’d never give someone who had never played a guitar before and say “alright, you’re playing tonight, there’s a big concert”. You’d be like, that doesn’t make any sense. Filmmaking is the same way. You just need a lot of practice and the more you do it, the better you get, the more you learn, the more you see.

The other thing is make sure to stay fed, you know. So, in other words, go to museums, go sketch people in the park, watch movies, get out there. I mean, I think that’s one of the reasons why John Lasseter really encourages us to do research at the beginning. Because if you have a very shallow pool that you’re pulling from, you kind of exhaust it pretty quickly. But if you’ve got a massive depth of all this stuff that you’ve looked into and know about, you’re just going to be able to go much deeper. 3

Every movie I’ve worked on has taken at least four years. Most of them have made me question why I was making it, my abilities as a filmmaker, and even my worthiness as a human being. Making movies is drudgery. It’s painful. It’s exhausting.

And it’s worth it.

Every chance I’ve had to create something was a gift that brought new depth to my life. If no one ever saw it but me, I would’ve still considered myself incredibly lucky to have had the chance. But every time you make anything, you have an opportunity to make influence someone’s life for the better. If someone laughs, or cries, or thinks more deeply about something because of something you created, it means you’ve connected with them – which is the reason we do this.

Connecting with people is what storytelling is all about. Yes, it takes a lot of work. And that work is a privilege, an art, and an opportunity. 4

Getting Ideas

“Where do you get your ideas?”

This is a question people ask a lot, and frankly it demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding about the creative process.

For some geniuses like Walt Disney or Miyazaki, their movies show up to them fully formed. Kapow: Dumbo. Pinocchio. Spirited Away. If you’re lucky enough to be born brilliant, ideas just appear all at once in your head.

I used to believe this.

But here’s the brutal truth: I’ve read through stacks of notes on nearly every Disney feature film. I’ve spoken personally to Hayao Miyazaki about his process. I’ve been privy to the development of every Pixar film. I’ve directed three myself. Not one of them appeared fully formed.

Great ideas are not given, they’re built. Every seemingly obvious and brilliant story takes years of refinement and adjustment. So the real question is not where you get ideas, but how do you develop them?

Frustratingly, there is no step-by-step process I can outline for you. Every project is different.

Creative work is a discovery, not a well-mapped excursion. You’ll get lost, and you should; if you don’t, chances are you’re doing something that’s been done before.

For some people, just getting going is the biggest hurdle. Personally, I don’t find starting as difficult as continuing. There are tons of ideas out there. But how do you tell which ones are “good”?

For me as I start, I’m just looking for something that excites me, for any reason. It might be a concept, a random joke, a new technique, a feeling, some experience I’ve gone through in my life (birth, lost on vacation, a breakup)… anything is fair game, and there are no rules. Monsters, Inc. began by thinking about beliefs I had as a kid (I knew there were monsters that lived in my closet waiting to scare me). Up started as my desire to escape everybody and get away from the craziness of the world. Inside Out got started by me thinking, “what concept would demand it look stylized, not realistic?”

I usually make a list of ideas. I don’t just go with the first thing that comes to me. Finding good ideas is like digging for buried treasure: you might find a coin or two on the top, but usually the chest full of doubloons is buried deeper.

But at this point there’s no judgment. Don’t listen to all those books that tell you how films need to fit a certain structure, and you need to know your theme up front. That’ll come later. The only rule at this point is: do I find this interesting? Does it make me excited to think more about it? 4

Developing Ideas

If I find an idea I like, I’ll just free associate. The idea grows and expands – every subject connects to dozens of others, and I add together stuff that seems to that fit together. Sometimes it mutates into something entirely different. Some ideas die out and cease to be interesting, or prove to have limited emotional depth.

What does the subject of Monsters make me think about? How do they get into kids’ rooms? What do the monsters get out of it? I ask a lot of questions and come up with a lot of answers – usually multiple answers for each, at first.

Author and cartoonist Mo Willems talks about ideas being seeds. You plant them, cultivate them, and nurture them. Many die. Others grow into small, exquisitely beautiful flowers. Others become massive trees that you can cut down and exploit for the lumber. But you can’t tell what they’ll grow into by just looking at the seed. 4

Three Elements To Look For When Writing

As I move forward in developing a project, I often find I’m looking for these things:

1. An engaging concept. (i.e. Monsters do exist, and they scare kids for a living.)

2. Emotional heart. (What happens when someone you love dies? When you break up with someone? When your kid grows up?) It should be something true, that you have dealt with in your own life. Something you struggle with, not something that has a pat answer.

3. Character. Not necessarily a nice good character, but someone interesting. Al Capone isn’t someone you’d likely want to live with, but wouldn’t you love to have had dinner with him?

Usually one or more of these elements is missing in my pitch, and I have to really think hard about how to get them. And unfortunately, they’re gossamer; just because they seemed solid yesterday doesn’t mean they’ll stand up today. I’m constantly reassessing and reevaluating. 4

Hard Work Trumps Talent

If you find yourself avoiding thinking about the project, it could be the idea is drying up. Or, you could just be lazy or scared, and are trying to avoid the real work. Because around now (if not before), you’ll probably hit a point where you seriously question the whole idea. Why did I pick this? Why did I ever think this was good? It’s a lot easier to give up and start something else.

Is it time to give this up and move on? Or should you keep going? How can you tell? Only you know for sure – but chances are you should give it another few days. I’m haunted by the advice of my mom: “There are some things in life that are not fun, but that you have to do anyway.” Developing these things are not always fun. In fact I’d put the ratio of fun to work at about 10% fun to 90% work. That’s probably generous. I’ve grown to love the work part too, but that took a while.

Some people say, “Don’t force it. If it’s meant to be, the idea will find you.” On every project I’ve ever worked on I’ve had to drive myself to keep going at some point or another. In the long run, tenacity trumps talent.

It can be hard to remain focused, especially for hours at a time, but the more you do it the better you get. It’s like working out; if you keep at it, you train your brain. 4

Getting Feedback

As I develop the concept, I will be seduced by sirens that lead me astray. I fall so completely for these ideas that I am not be able to see they’re not right for the film. That’s why it’s important (though painful) to show what I’m working on to other people that I trust. This is exciting and nerve wracking, because it could either be a huge boost of excitement and enthusiasm, or kill all momentum in a big wet blanket of criticism.

Showing other people is incredibly helpful, for two reasons. For one, pitching to others helps refine your story. Watching what people react to instinctively makes you adjust the story you’re telling and the emphasis you give it. I’ve read that Walt Disney would corner people to tell them the story of Pinocchio as he was developing it, and his story got better every time he told it.

Second, you’ll get new ideas and valuable reactions from people. They’ll like certain things and be confused by other parts. Try to be aware of their reactions while they’re watching or listening. Their reactions are almost more valuable than what they say later, because people react pretty honestly. Once they start talking, they may get caught up in being the expert.

In other words, getting feedback is not passive – you can’t just sit and listen to whatever they say. You have to silently judge and assess: where are they coming from? Does this idea fit in with what I’m trying to do? Or maybe: is it better than what I’m trying to do?

Remember that even brilliant people are not right 100% of the time. Only you know what’s right for your project. But know that if you choose to ignore notes, especially notes you get from many different people, you’re likely doing so at the cost of your film. 4

How To Focus On What’s Important For Your Story

Here’s a trick to help you focus: tell the story, from the main character’s point of view, in 3 sentences or less. This forces you to cut out all the details and superfluous stuff, and it also hopefully shines a big spotlight on the main conflict for your character (hopefully the relationship he/she has with another character). Remember this is not a homework assignment; you don’t get a good grade if you use just the right words. The exercise is only to help you focus on what’s important for your story.

Bill Hader often helps write on South Park, and he told us that creator Trey Parker has a saying: “Replace your ANDs with THEREFOREs.” In other words, events should happen for a reason, and should be caused by actions taken by your main character. Your main character did X, therefore causing Y to happen. 4

Characters’ Relationships Are Key

Through it all, I try to keep in mind the dual goal of all this: to express myself in order to emotionally affect the audience. The one accomplishes the other: I’m not here for my own therapy; whatever I say has to mean something to people. But ultimately that’s why I’m rewriting, testing and retesting my gut. Whatever I’m making is to entertain and emotionally affect the people who paid to watch.

If there’s one thing I’d underline for you, it’s this: focus on your characters’ relationships. That’s really the main thing we care about as humans. Why else do we so enjoy gossip? Why do we spend so much of our lives around other people? Even if you have great jokes, an amazing world you’ve developed, or even a powerful statement and theme, it’ll really only ever strike home for audiences through the changing interrelationships of your characters. 4

What Is Pixar’s Style?

Well, for better or for worse, I’ve never heard anybody in any of the meetings say, “Eh, that’s not Pixar enough.” But we’re definitely looking for character-based stuff. That’s first and foremost: that it’s all seen through the main character’s eyes and all motivated by the characters. Hopefully, all good movies are made that way. We’re also trying to appeal to the animator in us.

All of us so far, except for Lee Unkrich, who’s directing Toy Story 3, come from an animation background. There is something about animation that makes you see things in a certain way, and I don’t know what exactly that is, other than you start to see personality in almost everything.

Like, just looking at this chair [he points to a plush, cushiony chair], I can see a certain personality to it that another chair wouldn’t have. This one is a lot more sort of, [he assumes a gruff baritone] “Well, I’ll get around to it when I get around to it.” Just based on the design, it seems much more sedentary and overweight a little.

That probably lends itself to how we approach design as a way of trying to express physically what’s going on inside the character. Beyond that, I do think we try to think of ourselves as just regular filmmakers. We try to approach things the same way a live-action director would in terms of the way we shoot things. 5

Overcoming Creative Problems

One trick I’ve learned is to force myself to make a list of what’s actually wrong. Usually, soon into making the list, I find I can group most of the issues into two or three larger all-encompassing problems. So it’s really not all that bad. Having a finite list of problems is much better than having an illogical feeling that everything is wrong. 6

Directing Voice Actors And Animators

When I first started, I thought my job was to have everything in my head, almost like a pre recorded vision of what it should be. And then I would listen and try to direct to that. And I realized, especially as I work with amazing actors, like Bill Hader, and Mindy Kaling, really, what I want to do is set the table and that let them play, because I’m going to get better stuff. If you’re able to kind of say, “Okay, this is what we’re doing right in here”, but don’t define it so precisely, then there’s still a lot of experimenting and playing to do.

You want to know enough about where you’re going to be able to lead them, right? If you’re like, I don’t know what’s going on, then nobody else does either. For example, even in talking to animators, rather than saying, “okay he comes in and he very quickly puts his hand on the glass, and then 15 frames later he goes like this”.

Instead I’m going to say “you know that feeling when you come home from a long hike, and you are just drenched with sweat, and you’re so thirsty, that is what he’s feeling like as he comes in”. When describing what you want in this way, they can create and put in their own specifics of how that’s going to happen.

So you’re setting a scene, more of an emotional thing for them. And the same with lighting. Same with the live actors. As much as I can kind of create the scene in their head and describe the feeling, then they’re going to fill in their own specifics and bring great ideas to it. 2

Advice To Middle School Students

The following is a transcript of a letter Pete Docter wrote to middle school students, advising them not to give up on their dreams and do what they love.

What would I tell a class of Middle School students?

When I was in Middle School, I liked to make cartoons. I was not the best artist in my class — Chad Prins was way better — but I liked making comic strips and animated films, so after High school it was no surprise that I got into The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), a school that taught animation.

CalArts only accepts 25 students a year, and it attracts some of the best artists in the country. Suddenly I went from being one of the top artists in my class to being one of the absolute worst. Looking at the talented folks around me, I knew there was no way I would make it as a professional. Everyone else drew way better than I did. And I assumed the people who were the best artists would become the top animators.

But I loved animation, so I kept doing it. I made tons of films. I did animation for my friends’ films. I animated scenes just for the fun of it. Most of my stuff was bad, but I had fun, and I tried everything I knew to get better.

Meanwhile, many of the people who could draw really well kind of rested around and didn’t do a whole lot. It made me angry, because if I had their talent, man, the things I would do with it!

Years later, a lot of those guys who probably still draw really well don’t actually work in animation at all. I don’t know what happened to them. As for me, I got hired at Pixar Animation Studios, where I got to work on Toy Story 1 and 2, direct Monsters, Inc., and Up.

So, Middle School Student, whatever you like doing, do it! And keep doing it. Work hard! In the end, passion and hard work beats out natural talent. 7

A short note

Each Sunday, I share a free email called The Creative Capsule featuring two carefully chosen works: one album and one film.

It’s short, ad-free, and designed to help you decide what to watch or listen to without scrolling.

Next up: Guillermo del Toro on His Job As A Director

- Pete Docter spills the secret to finding originality in your work, The Academy, Twitter

- PETE DOCTER | In Conversation With… | TIFF 2015, YouTube

- Advice to New Filmakers From the Makers of ‘Inside Out’ | SIFF TV, YouTube

- Pete Docter: On Developing Story Ideas, Artella

- An Interview With Pete Docter By Christopher Orr, The Atlantic

- Creativity Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration, 2014, By Edwin Catmull, Amy Wallace

- Passion and hard work: Pixar filmmaker’s inspirational letter to kids, Daily Edge

Notes & Sources

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week.

1 painting, album, film, and book recommendation every week. Download your free creative reset guide

Download your free creative reset guide